The perfume counter is a quiet place most of the day. Yet there she is, the Perfume Lady, surrounded by all of these perfumes, waiting for someone to pop by. Each bottle, a character. Can she say they are her friends? She knows them all so well by now; their notes, their moods, their behaviour — all hidden within these clear liquids and glass bottles. Some round, some square, some with a heavy metal top that magnetically snaps when you put it back on. To polish these bottles, by the way, is a handy way of looking busy when working in a perfume shop. It’s the kind of labour that suits the Perfume Lady as she ceaselessly perfects her role through meticulous small tasks. A cotton pad dabbed in alcohol removes the fingerprints from bottles belonging those who’ve tried the different perfumes as if it was day-four nail polish that has started to peel off, leaving the half-empty bottles with an immaculate shine. It would be fun to find out who these hands that once touched the bottles belong to, but she doesn’t need their fingerprints to know that. They way a perfume sits on someone’s skin is like a fingerprint of its own, making the Perfume Lady a well prepared investigator. Sometimes she can even imagine the right scent for a customer before they have entered the store properly. Just a quick glance, and she already sees their character in notes and facets, nerolis and musks, reflected in the imagined persona existing in every bottle.

Just as the Perfume Lady knows the personalities kept inside these hundreds of bottles, she knows their customers when she sees them. She remembers what regulars put on in the morning, wear for a night out — the scents of their childhood memories and father issues alike – at least that is her aim. But she also sees prospective wearers, trying to see what they would smell like if their shoes and bags, walking styles and hellos were scents. She takes pride in her guessing, because it is her profession, and she’s really good at it she has to admit to herself. The Perfume Lady doesn’t simply love the hundreds of different scents she works around, but she loves the fact that her dedication and expertise can help people finding the scents representing their hopes and fears and crushes and dreams. Sometimes she finds her immediate guess to be so boring, so predictable, and instead she ends up going on a detour through lots of other scents before she finally returns to her initial idea, and finds it to be spot on.

To be a connoisseur of scents is not only being able to spot a top note, a heart and a bottom. It also involves the responsibility of finding a wearer for each scent. The skin they would suit, the person they long for. Some of the bottles spend days getting dusty on the shelf, until one of Perfume Lady’s cotton pads, held between French-manicured fingertips, comes and cleans it up, stroking its glassy curves affectionately, showing them that they have not been forgotten. This is her job.

They all say they like the same things. Or they say they are unique and demanding, but in the end all of them find themselves looking for the same thing. The Perfume Lady wonders how many of the bottled characters come from imagined personas, like a whiff of Eve coming alive through warm ebony notes and green fig leaves. She wonders if she would detect the smell of middle-aged women with their practical backpacks and hiking shoes if they didn’t all wear the scent smelling of mountain mists mixed with laundry detergent. There are also the the architecture students with their dark shades of blue who all like the same woody, warm scents, as if the perfume was an extension of their modernist furniture aura. Then there are the girlies with fake lashes and shape wear who always get attracted to the golden bottles by the window. She regularly asks herself: did it start with the smell, or did it start with the person?

The Perfume Lady sees people walking into the shop and she likes to think she knows what they want. Often, she is right. It has to do with how they are dressing, obviously, as — statistically — shape wear like amber scents whereas leather jackets suit fresher, wooden scents. When The Perfume Lady says statistically, she means based on the little notebook she keeps under the counter for quiet hours when she is tired of removing fingerprints from bottles, or is exhausted from smelling her way though a few too many scents. It can really wipe you out, she can tell you all about it. It can make you numb and hazy, so after inhaling ten, twenty, thirty scents with regular intervals, one will need a break. Some fresh air or just a sit-down on the stool behind the counter usually helps. It is a bit like social fatigue, one might think. All these scents, all so full of character, vying for attention. Which she is happy to give them, most of the time, but as with everything good, one will need a break. Sometimes a cigarette is tempting. Cigarettes are bad for you, the Perfume Lady knows so. They are bad for her well-treated skin and for her advanced sense of smell — it is scientifically proven. The cigarette, a real disruptor! But she rarely smokes during working hours, it can wait until closing. She takes pride in her work, and she doesn’t want to come across as unprofessional if a potential customer would come by, seeing her, choosing the smell of cigarettes instead of perfume. Deep inside, her real fear is that cigarettes will make her look like an old-fashioned Perfume Lady. Someone with pearls and perms and a halo of cigarette-infused jasmine that she remembers from visiting perfume shops as a child. It is a difficult one, she has to admit. That kind of woman is the Perfume Lady who inspired her to choose the career she has today — with an unimpressive salary but with a sensory abundance. But to become like like her would nonetheless imply that she is an old-fashioned cliché.

That being said, the smell of a smoker works well with certain scents. ‘Portrait of a Lady,’ for instance, is such a smoker’s perfume. Portrait of a Lady is made for a woman who unapologetically smokes. Sometimes the Perfume Lady puts it on, sometimes she want to be this woman she is not, who is bold and confident in her femininity. Just like its regular wearers tend to come in with red lips, rusty voices, magnetic personalities on the verge of being a bit too much. But the Perfume Lady is not a bit too much. It is always fun playing dress-up with perfumes like this, but behind the perfume counter she is expected to be mild and gentle, professional and generous. In the shop, a perfume is supposed to shine on the skin of the customer. To make sure this happens, she provides the confidence of a guide, looking them in the eyes when they describe their needs and desires. She tells them that she knows exactly what they will like. She shows that she is listening intently to their version of the scent. There is no wrong impressions; the customer is always right. Her gentleness invites her to smell their wrists and necks, sharing her opinions as if she was a close friend. The Perfume Lady is almost like a therapist, dealing with intimacy through a dance made up of a specific sequence of steps that leaves her at a distance while feigning the illusion of closeness. Of course, it is difficult not getting confused here and there. She is invested in this job, these people, and she goes into character as the Perfume Lady to a point where she wonders if she isn’t in fact the one who needs to act out a suppressed part of herself.

She goes to work and she turns into the lady at the perfume counter. As with anything you do enough times it has become natural, but she still sees herself in the reflection of makeup mirrors and perfectly polished bottles, wondering whether she’s turning into the Perfume Lady more permanently than a perfume’s average longevity. She is personal yet professional, feminine yet confident, seeing their needs, giving them advice, making them all smell wonderful. Not everyone can do what she does she thinks to herself in the mirror, as she wonders if people working in clothing stores feel the same way. If they perform the same roles and fulfill people’s needs on the same level as she does. Clothing stores seem to be a rare occurrence these days, anyways. In the fast-fashion flagship across the street from the perfume shop, the workers constantly shout at each other over the speakers. Jenny at checkout eight, Jenny at checkout eight! And the Perfume Lady runs out onto the street again. This was not what she needed, someone screaming. She knows it is not directed towards her, not directly, but well, why bother pausing the thumping music in the store to do the screaming over speakers?

In some way, you may say that the Perfume Lady is doing a better job than the clothing store in dressing her customers. She likes to think of different scents as different textiles, draping the body in their own, personal way. She smells iris and imagine different textures of silk. A bit cold, slightly reflective, soft and smooth as if touching the scent with your fingertips. She smells light musks like a white t-shirt one accidentally has fallen asleep wearing. Magnolia is pleated tennis skirts, while myrrh is layers of brown velvet. And with bit of patchouli, it turns into a voluminous skirt that dances when you walk. Alone, on the other hand, patchouli can be that old, thick woollen jumper that becomes nicer the closer it is to falling apart.

This reflection is highlighted through the Perfume Lady’s own choice of attire at work. Modestly yet elegantly dressed in jeans and flats, and a top that doesn’t say too much, she tells the world that she has an eye for detail and that, in the perfume shop, she has decided to channel her good taste and openness for experimentation towards her nose. She is not the one to take up space, to scream over speakers.

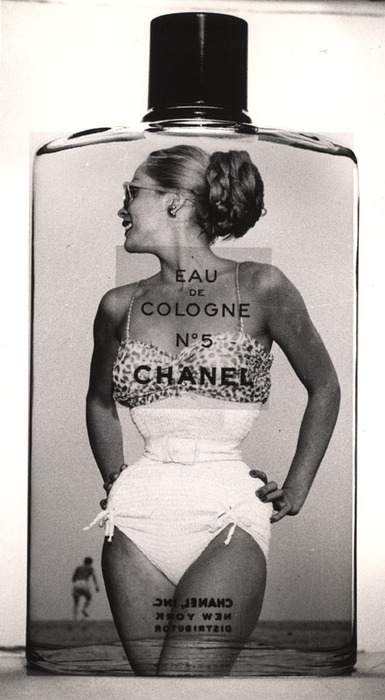

She plays a role, but does she embody a cliché or a classic? Everybody knows the Perfume Lady from popular culture, right? She is part of the canon, we can all imagine her behind the makeup counter of some old Hollywood film where the plot has been forgotten long ago, but the delicate interactions between hands, cosmetics, and women in the same situation are exchanged. In the same way, the Perfume Lady holds a place in modern history as one of the first jobs by women, for women, as they were trading eau de cologne for the ability to build a career and life of their own. Simultaneously, she gave women a place to come to her with their hopes and fears, curing all kinds of stuff with some retail therapy: a new scent to live out a part of themselves, otherwise suppressed by screaming children or demanding husbands. The world may have changed, but the expensive and delicate escapism of a new scent during one’s lunch break persists, just like the Perfume Lady continues to perform her perfect, delicate service for her customers.

In comes the occasional man, too. But usually, there are just all these girls who all buy a bottle of vetiver for the guy they are in love with — guys who she never hears about again, guys who never return to the perfume store for another bottle. Yet imagine all the exes that exist inside that bottle, the Perfume Lady likes to think. Beautiful, unavailable men. Oh, how much the Perfume Lady longs for such a man to pop by, so she can look into his eyes, smell his strong wrists, and be fulfilled with the feeling of a perfectly textured scent blending with a beautiful and masculine undertone. The Perfume Lady never forgets a stunning man — she thinks about him quite regularly, in fact — with his fancy bike and expensive watch, walking straight into the store and getting himself a bottle of that bubblegum-scented jasmine. How unexpected! How delightful! She thinks about that encounter often, and wonders if she does so because she would never have suggested that scent for him herself.

After work, she goes out with her fellow Perfume Ladies for drinks. The lot of them in bars, sitting on high stools, complaining about the absent men in their lives and gossiping about new scent releases and annoying customers over glasses of pricey wines — it’s payday and the Perfume Ladies work to sustain this tradition. They smoke cigarettes, like real Perfume Ladies do, and they stay out late. They complain and comfort each other in this company, talking about demanding customers and failed dates as two sides of the same thing. They smell each other’s wrists, but the affection is of its own kind. By sharing the knowledge of how it is to be a Perfume Lady, they reinforce their roles by continuing to play their part after the shop is closed. How can they not? The scents from the working day still linger on their skin, a mixture of all things sprayed thought the day, diluting each other into the generic scent of the Perfume Lady.

The Perfume Lady doesn’t have a scent of her own. She is everything sprayed and stuck to her hands, memories of a day of devotion to some other person’s wrists and Proustian madeleines. But just as much as she likes to know everyone else’s scents and needs, she likes to keep her identity to herself. She is, after all, playing her part.

Emma Aars is a Norwegian writer living in Glasgow and Oslo. Her first essay collection Eye as a Camera was released by Objektiv Press this year.