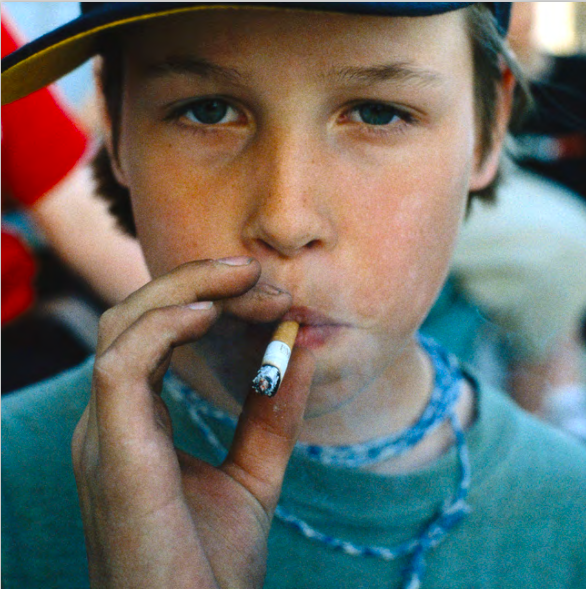

AT THE END OF the twentieth century, American culture figured the knowledge of its teenage population in curious ways. What teenagers knew – ‘You think you know everything!’ their mothers said – was interesting and even profitable, because it was knowledge without agency. The teenager knew, in that she understood the economies, family, schools, institutions, and other systems in which she had appeared, as a result of having been born on planet Earth, in the United States, and, after this, having been subject to the whims of others. The teenager knew, because she had observed the adults. She was attempting to become them. Meanwhile, things were being sold. And the things being sold to her, the teenager, were offered for sale with the knowledge that the teenager did not have a salaried job, nor did she possess other mobilities and freedoms. Again, the teenager knew – perhaps, even, everything – but she could not do much about it. She was a boy or a girl and a minor; possibly she was chattel.

American teenagers of the 1990s were renowned for shoplifting, for working service industry jobs, for purchasing (and sometimes shoplifting) CDs, for dealing and consuming drugs (some of which were prescribed to them by psychiatrists), and for having a poor work ethic, which they allegedly broadcast to the world by wearing clothing they had purchased second-hand or discovered in the trash. These tendencies were all but instantly sold back to them in the form of additional CDs, magazines, movies, and inexpensive clothing that was designed to resemble the even more inexpensive clothing they had been buying second-hand or finding in the trash. Some teenagers had the means to buy these things. Others only observed, wondering if there was such a thing as ‘the authentic.’ But everyone knew.

All the teenagers in America knew everything. I know; I was one of them.

Of course, times have changed. We are in the late – senescent, even – period of the notion of the teen, a moment at which the competing category of ‘tween’ has already long since had its day as a neologism, and the havoc wreaked by the internet on the boundary between public and private life is affecting our ability to comprehend all sorts of narratives. I’m not even sure if you can be a teenager, anymore. Or, for that matter, if there’s anything so special about being a teen. I mean, certainly, you can be fifteen. But it is not clear that it is so very unusual to be an individual who knows everything, but/and can do nothing about/with that knowledge. This particular cultural position seems to be increasingly – and perhaps even disturbingly – well shared out. Now everyone is always on the phone.

In a recent article in The Atlantic proclaiming the end of the teen, as such, Jean M. Twenge describes the lives of teenagers in the following way: ‘… the lure of independence, so powerful to previous generations, holds less sway over today’s teens, who are less likely to leave the house without their parents. The shift is stunning: twelfth-graders in 2015 were going out less often than eighth-graders did as recently as 2009.’1 Twenge, a psychologist who studies intergenerational differences, blames smartphones, along with the unremitting access to social media these devices provide. Contemporary teens are not rebelling or experimenting; they lie around in bed all day screenshotting Snapchat. In the past, American teens had sex and drove; now, according to Twenge, they are more likely to blackmail each other with vaguely illicit, or maybe merely dorky, digital images. Safe in their bedrooms, teens know more and more (they study affect and interpersonal discourse in obsessive detail) and do less and less. One might ask: If they do not become influencers and/or entrepreneurs, are contemporary teens accorded any place in the popular imagination at all?

While I find Twenge’s description of the habits of young Americans plausible, I am myself drawn to different sorts of questions, regarding generation- al shifts. If the ‘old’ teenager, the teen of the twentieth century and perhaps the aughts, was not just a risk-taker or rebel but someone who tried on various adult identities without having to adopt a single one, the end of the teenager could also imply the end of the adult – or, rather, the end of the adult as someone who has chosen a fixed identity for him- or herself. Lives are more reconfigurable – and later on – than perhaps ever they have been. Those who lose spouses go online and find new ones. Those who lose jobs obtain new educations. We comment on articles and videos online as people we are not. As a reticent user of social media, I sometimes fantasise about creating a pseudonymous account or two, via which I might (safely, from the comfort of my bedroom) post and comment as someone other than myself – vociferously, meaninglessly, endlessly. None of it’s malicious, I promise you…

I am a teenager?

But, by the same token, who wants to be a teenager? Who really wants to be that old teen, a minor, in permanence? Someone who has bows in her hair, favours Hello Kitty and Minnie Mouse accessories, dots ‘i’’s with a star, clutching her books to her chest. Someone who wears oversized clothing, speaking softly, with his head bowed, recoiling if anyone tries to touch him. Someone with a certain warmth in her demeanour, a hopefulness, who appears to be in distress. Whose skin is without wrinkles, whose hair shows no traces of gray, who looks like a lost girl needing help. Who is indistinguishable from the teenage mob, waif-like, an androgynous figure hiding behind sunglasses, with a girlish, whispery voice?

The language in the previous five sentences isn’t even my own. It’s taken from reporters’ accounts of adult men and women who have pretended to be teenagers,2 a confidence maneuver that’s surprisingly common – and perhaps most surprising, in that it occurs at all, for, as noted above, who really wants to be a teen? Among these artists of the teenage con, these ‘old teens,’ are Treva J. Throneberry, Charity Johnson, and Frédéric Bourdin, all of whom were eventually arrested for activities related to their charades and who are richly represented online. Throneberry pretended for over a decade to be fourteen, fifteen, or sixteen. She presented herself as a fresh-faced, pigtailed runaway in need of shelter and schooling in communities all over the U.S. and was largely successful in her act, even as a twenty-eight-year-old. Johnson found many of her marks, women looking for girls in need of a substitute parent, on Facebook. She used Instagram to post adorably captioned soft-focus selfies (‘honey bee love’), and at age thirty-four she successfully enrolled in the tenth grade. The protean Bourdin lived for many years in and out of foster care in Western Europe, speaking multiple languages, hiding his bald spot beneath various forms of teen-appropriate headgear.

Aside from the obvious reasons to be interested in people who engage in these sorts of ‘cons,’ I am interested in them because teenagers are minors; to pretend to be a teenager is to pretend to be a minor. Minors cannot engage in consensual sex with non-minors. Minors must go to school. They may not legally consume alcohol. They cannot vote. To pretend to be a minor when one is not a minor is to in fact possess agency under the law but lie in order to give that agency up, at least superficially. As an old teen, you must establish relationships with proxies, guardians, schools, and other caretakers in order to survive, to have the basic necessities of life. Your relationships with other adults are further circumscribed by the role you are playing. In return, you get to start over, to be too young to know better, to be continually vulnerable and perhaps confused and just beginning – for as long as you can keep the con up. In at least two of the cases mentioned above, even obvious physical signs of maturity like baldness or dry, aging skin were not enough to unmask the old teen. Many marks seem to have been blinded to such obvious contradictory physical evidence by pity, a fact that makes more sense the longer one ponders it.

Old teens are playing both sides of the political gambit. They inhabit the position of deceiver and victim simultaneously, through the form of their chosen con. If earnest and naive, they are ironically, falsely so. If they seem emotionally open, they are engaged in a complex fiction. If they seek affection, it is on duplicitous terms. Yet, old teens, either by reputation or admission, are seldom grifting for money or power. What they want, they say, is authentic, unconditional love. The search for love is a strange knot, for in this quest the old teen is bound to fail. Old teens ask their marks to love someone who does not exist, to raise someone who is already grown. Thus, it’s not just the cunning of the old teen that must puzzle us but also this: Why engage in so elaborate a plot that must, inevitably, fail? Why take such risks for such seemingly minor (please excuse the pun) material rewards?

As I was researching the ‘old teen’ – reading, for example, about Treva Throneberry’s high school romance, or Charity Johnson’s search for surrogate mothers on social media – I had a strange experience: I started to believe I was one. Maybe this was just an instance of the same weird mimetic logic that attends WebMD self-diagnoses, but it might be something more. In particular, Frédéric Bourdin’s bizarre masquerade as a missing American teen he did not even resemble struck me weirdly familiar. (Had I not somehow lived this sort of life, too? I found myself asking.) To escape difficulties created by his confidence ploys as an old teen, Bourdin fled France by pretending to be Nicholas Barclay, a thirteen-year-old Texan who had disappeared three years earlier. Bourdin was ‘repatriated’ to the U.S. and entered the Barclay family drama as a more or less prodigal son. The reason this deception worked for a time, was that some members of the family in fact knew what had happened to Nicholas (he had not disappeared but had rather died).3 There were at least two cons running at once, and these were even mutually reinforcing. Thinking this through, I began to see the charade of the old teen as more and more recognisable. It wasn’t just that I remembered being a teen and what that felt like, but that I began to see the old teen as a figure for our times, in which the meaning of biological age is so strangely fungible. Now, there is such a thing as a teen only if anyone can be one. There are no more teens, and yet teens are everywhere.

Lucy Ives is a New York City based poet, novelist and critic. She’s the author of more books than will fit on this blurb – the most recent being Loudermilk: Or, The Real Poet; Or, The Origin of the World.

This article was originally published in Vestoj: On Authenticity, available for purchase here.

J M Twenge, ‘Have Smartphones Destroyed a Generation?’ The Atlantic, September 2017. ↩

K J M. Baker, ‘Forever Young,’ Buzzfeed, September 18, 2014; Y Desta, ‘Whatever Happened to JT Leroy?’ Vanity Fair, August 22, 2016; J Gerstein, ‘8 Cases of Adults Impersonating Teenagers, The Frisky, June 12, 2012; D Grann, ‘The Chameleon,’ The New Yorker, August 11, 2008; E White, ‘Forever Young,’ The New York Times, March 10, 2002. ↩

D Grann, ‘The Chameleon,’ The New Yorker, August 11, 2008. ↩