‘TO CREATE A BEING out of oneself is very serious,’ wrote the late Clarice Lispector in her 1973 work, Água Viva.1 The personal branding needed to attain commercial success and visibility in today’s fast-paced, oft-intersecting fashion and literary circles lends Lispector’s words a strangely prophetic resonance. For women in the arts especially, the necessity to carefully craft a desirable public image – particularly by paying close attention to personal style – so often determines the content of the conversations that arise around their work. However, this perceived glamour of mid-twentieth century figures, like Lispector, conveniently overlooks the literary integrity of their work in order to generate profit.

It’s tempting to accept the consumer-ready packaging of female writers, musicians, and artists in fashion industry-vetted contexts – whether they appear in ad campaigns, magazine covers or screen-printed on tote bags – at face value. Yet it’s worth questioning whether this packaging serves them and their work as holistically as possible; whether it builds and sustains an audience legitimately interested in the work itself or one that is merely attracted to the glamorous façade.

The daughter of Jewish immigrants born in a highly anti-Semitic climate, Lispector and her family emigrated to Brazil in 1921 when she was only two months old from Tchetchelnik, Ukraine (Russia) to escape the pogroms. Lispector often attributed this early disruption to ‘her sense of not quite belonging, especially to herself.’2 While she adopted Brazilian Portuguese as her primary language, her marriage to a Brazilian diplomat took her to temporary homes in Italy, Switzerland, England, and the United States. Beginning in her teens, writing stories allowed her to make sense of her inner conflicts concerning gender roles, class struggles, economic status, and her own complicated cultural background; hers was a metaphysically curious writing style, one that often raised questions about the nature of being human in strange and haunting ways. Lispector led a varied and highly productive career – publishing novels, stories collections, children’s books, and even a weekly column for the national daily newspaper, O Jornal do Brasil – and won various literary awards, eventually becoming an undisputed literary legend in Brazil. Yet it has taken decades since her death in 1977 for her singular voice to reach English readers in translation.

For a writer so strongly invested in mining her complex inner world for material, Lispector’s exterior has received a disproportionate amount of attention. Today, it’s rare to encounter reviews of her work that do not reference her ‘glamour’, an adjective frequently associated with her appearance. As Benjamin Moser, one of Lispector’s biographers, points out in his introduction to the recent reissue of The Complete Stories, ‘The legendarily beautiful Clarice Lispector, tall and blonde, clad in the outspoken sunglasses and chunky jewellery of a grande dame of mid-century Rio de Janeiro, met our current definition of glamour.’3

A simple internet search of images of Lispector reveals a woman who exudes the sort of visual presence that, at least on the surface, appears utterly effortless: she was prone to painting her lips a deep rouge and donning statement necklaces, her hair elegantly swept off her face. In many of these images, she gazes off in the distance while a lit cigarette dangles between her fingers. Lispector’s strong sense of personal style (she even moonlighted as a fashion writer) signifies that she was well aware of the power of her appearance to generate curiosity along with higher book sales.

The conflation between displaying genuine respect for her literary talent and obsessing over her distinct brand of glamour is evident in American translator Gregory Rabassa’s frequently quoted description of Lispector: he ‘recalled being “flabbergasted to meet that rare person who looked like Marlene Dietrich and wrote like Virgina Woolf.”’4

Despite the fact that Lispector’s first novel, Near to the Wild Heart (published in December 1943, around her twenty-third birthday) earned her impressive accolades – one critic even called it ‘[…] the greatest novel a woman has ever written in the Portuguese language’5 – she maintained a difficult relationship to the press for much of her career. Her hesitation to divulge information about her personal life, along with her distrust toward journalists to tell her story authentically, without layers of projection, led to a mythologising of Lispector that remains tied to the very mention of her name today.

It seems that this impenetrable Lispectorian mystique has only served to add to her appeal. In Brazil, she is a household name, long considered to be one of the country’s most significant writers. Recently, beyond the Brazilian borders, critical interest in her work and translated reissues of her novels and stories have steadily increased over the past decade.

Yet as Moser points out in his biography of Lispector, Why This World, ‘The legend was stronger than she was.’6 This legend overshadowed the woman herself, a fact that frustrated Lispector throughout her lifetime. Writing in 1976, the year prior to her untimely death from cancer, she reflected on the increased attention she had steadily gained over the years as her legend grew:

‘This all leaves me a bit perplexed. Could it be that I’m fashionable? And why did people complain they didn’t understand me and now seem to understand me? […] The truth is that some people created a myth around me, which gets in my way […]’7

Lispector correctly believed that the press considered her a slate onto which they could project their own assumptions about what went on in her head, rather than portray her as a multifaceted woman: equal parts writer, housewife, and mother. No matter how much widespread praise Lispector’s writing has attained post-mortem, her literary credibility will forever be bound to this glamorised mythology.

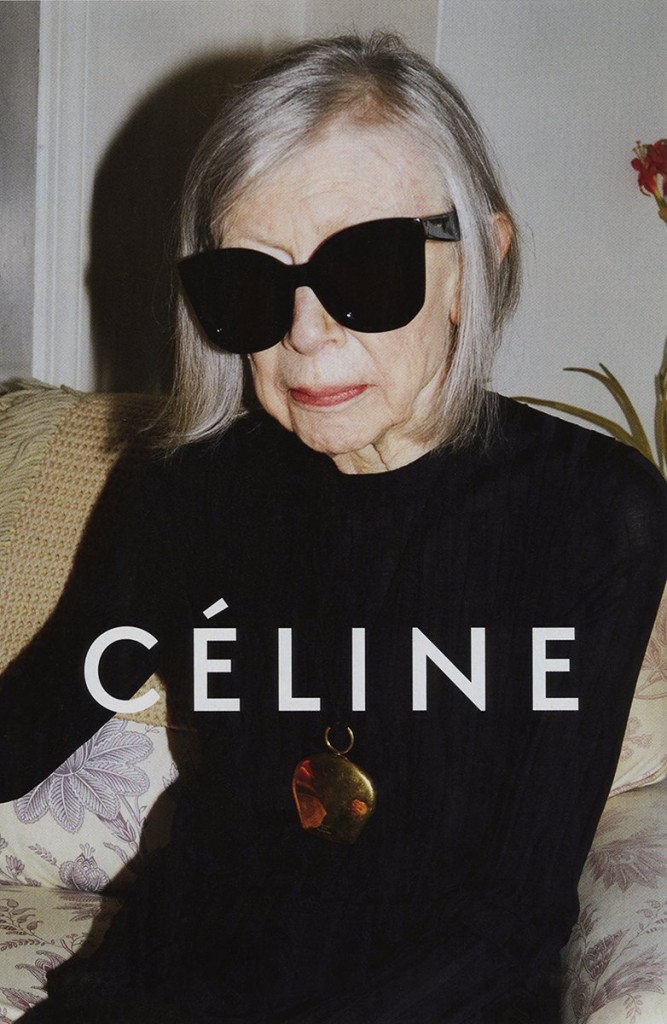

Similarly to Lispector’s experience once she found herself in the public limelight, the fashion and literary worlds alike have, in recent months, created their own sorts of mythologies around other artistic women – from Patti Smith and Iris Apfel to Joni Mitchell and Joan Didion – by collaborating with them, casting them in ad campaigns, and bestowing upon them the title of ‘style icon.’ As fashion and publishing houses alike have increasingly promoted, and ultimately profited from, the commercialisation of these independent, sartorially savvy, women, they have attained a new kind of cultural clout since their heyday in bygone eras. A conflict comes into play, however, when we claim to respect a female writer’s work while simultaneously idolising her desirable aesthetic. This dynamic has been further reinforced in the case of writer – and recently crowned ‘style icon’ – Joan Didion, following her role in the spring/summer 2015 Céline campaign shot by fashion photographer Juergen Teller and released last January.

Didion’s blunt reaction to the New York Times reporter who called her to comment (“I don’t have any clue,” and “I have no idea.”)8 suggested a reluctant ambiguity toward the fashion world’s embrace of her as a cultural figure worthy of admiration. Yet while Didion claimed an unawareness toward the buzz surrounding her style, there is no denying that both Céline and Didion benefitted from perpetuating the idea that she – and by extension, her work – were worth discussing anew, in part because of what she wore and how she wore it. As a recent New York Times piece by Matthew Schneier exploring the Didion fashion phenomenon confirmed, ‘According to Nielsen BookScan […] sales of her work in 2015 to date are up nearly 55 percent over the comparable period the previous year.’9

Designers and editors alike are clearly not blind to the commercial benefits of aligning themselves with these established, powerful muses whose personal style can be whittled down to singular garments and accessories that signify an insouciant cool: a pair of oversized statement shades for Didion; an old black coat and clean white shirt for Smith; dark red lipstick for Lispector. Theirs is an everyday way of dressing defined by distinctive simplicity, something the image-saturated and seasonally-spinning fashion universe so often lacks.

The ways in which women like Lispector and Didion have been marketed more recently for public consumption – attaining the status of both literary and unconventional style icon, respectively – highlights a tendency for such figures to offer the potential for increased cultural capital, specifically when viewed through the lens of nostalgia. Built as it is on maintaining a perpetual longing for times and places past (e.g. Lispector’s glamorous 1940s style; Didion’s 1970s California cool), this sort of iconic, nostalgic branding generates a significant profit. Other women, especially younger women, will inevitably try to emulate this iconic sartorial or writing style to feel closer to the women – by purchasing a pair of Céline sunglasses to look just like Didion or proudly displaying a copy of Lispector’s story collection on their bookshelf, for example. Yet given the logic underlying the very idea of a ‘style icon,’ which requires that they remain peerless, faultless, and perpetually out of reach, it is no coincidence that for the brand or publisher, this unfulfilled longing for closeness to the idol translates into increased accessories and book sales.

As so often occurs to suddenly embraced entities in fashion’s orbit, these writers’ fashionable auras may inevitably begin to lose some of their lustre over time. Still, the question remains as to whether fashion’s stamp of approval ultimately helps or hurts the female artist in question in the long term. If nostalgic branding encourages consumers to stop short at the glamorous image – to purchase the writer’s work solely on the basis of that image – then it risks less serious critical attention being paid to the work itself.

As the sudden, intense resurgence of interest in both Didion’s older works and Lispector’s translated works in the US have shown, the current expectation for female writers to also embrace themselves as profitable brands puts their work in danger of dilution. If the fashion world continues to ghost these women’s significant contributions to the long male-dominated literary canon on the gendered basis of their distinctly ‘feminine glamour,’ then it will perpetuate the idea that their writing is not capable of speaking for itself – that it cannot be divorced from what the woman wore while she wrote her life’s work.

Olivia Aylmer is a New York-based stylist, writer and graduate of Barnard College at Columbia University.

C Lispector, trans. Stefan Tobler, Água Viva, New Directions, New York, 2012, p. 39 ↩

Vieira, Nelson H., “Clarice Lispector.” Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia. 1 March 2009. Jewish Women’s Archive. ↩

B Moser, The Complete Stories of Clarice Lispector, New Directions, New York, 2015, p. ix ↩

B Moser, “Introduction: The Sphinx,” Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector, Oxford University Press, New York, 2009, p. 2 ↩

Ibid., p. 125 ↩

B Moser, “Introduction: The Sphinx,” Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector, Oxford University Press, New York, 2009, p. 4 ↩

Ibid., p. 361 ↩

Jacobs, Alexandra. “Joan Didion on the Céline Ad.” New York Times, 7 Jan. 2015. ↩

Schneier, Matthew. “Fashion’s Gaze Turned to Joan Didion in 2015.” The New York Times, 18 Dec. 2015. ↩