A moving image: a line-up of women in a public plaza, singing. Their words, in Spanish, are potent and chilling. They roar, voices in synchronicity: el violador eres tú – son los pacos, los jueces, el estado, el presidente. ‘The rapist is you – it’s the police, the judges, the state, the president.’ And then, a sudden shift as the choreography spurs into a dance, and a repeated chant unleashes: ‘and I am not guilty, not because of where I was or how I was dressed.’

In November last year dozens of women gathered in the city centre of Santiago, Chile. They stood in the street, then lined up in a neat formation, many of them deliberately wearing what could be deemed as scantily clad and striking ensembles: shiny or sheer tops, short skirts, tight shorts, colourful sequinned pieces, big hoop earrings, red lips, black eyeliner, and all sorts of sartorial variations. They wore black blindfolds over their eyes, and many displayed bright green scarves on necks or wrists. The breathtaking performance was summoned by a feminist collective called Las Tesis. It began as a mighty street act in the coastal city of Valparaíso and quickly spread in unforeseen proportions.

The choreography, the lyrics and the iconography were all quite deliberate in their symbolism. The lyrics referred to the recent Chilean political climate, which includes the dramatic protests that unleashed last October due to an increase in the cost of public transportation. But it also related to the public force and their violence, to a history of dictatorial repression and to something that is not just a Latin American reality but also a global one: the alarming statistics in which women are murdered and raped. The lyrics also hinted at the one that is sung by the Chilean police, as a sign of subversion. Duerme tranquila, niña inocente, sin preocuparte del bandolero, que por tu sueño dulce y sonriente vela tu amante carabinero. The green scarves evoked the energetic movement that has been sparked in neighbouring Argentina, where it has come to represent free and safe reproductive rights for women in a country where abortion is only legal as a result of rape, or when the mother’s life is deemed to be in danger. The garment has dispersed through the region, becoming a material representation of contemporary Latin American feminism.

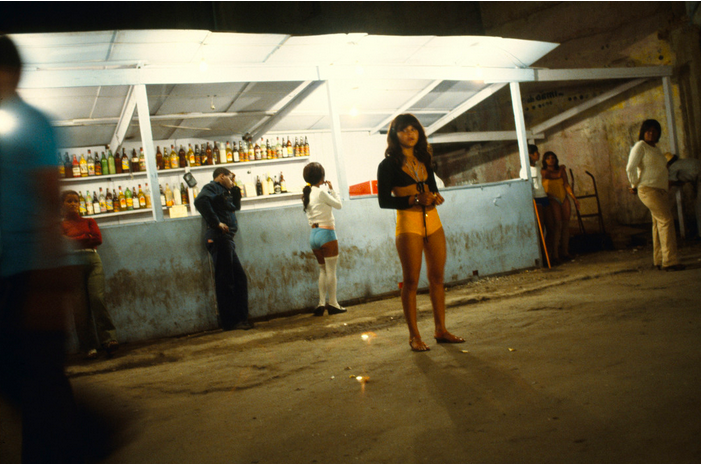

The ensembles chosen for the performance evoked the ways in which women often dress to have fun and to dance, to be young and alive at night, in bars and streets and discos, but they are also reminiscent of the kind of clothing a woman might wear when she is raped or killed. These are the kind of outfits that are still moralised within the sort of male gaze that inherits a cultural tendency to assign guilt to the feminine subject and not the masculine agent. These are the sort of clothes that call to mind the throbbing question that arises all too often when a woman is raped: what was she wearing?

The song, ‘Un Violador En Tu Camino’ quickly became a viral hymn. Replications of the performance ensued in Paris, Istanbul, New York, México City, Bogotá, Cartagena, Madrid. The lines of the song were transformed into digital images on Instagram; Twitter was flooded with its phrases, and women were struck by the chilling power of the words.

In Colombia, the repetition of the performance coincided with an unprecedented sprout of social protest spreading through its various cities. On Monday, November 25th 2019, a feminist march that had been in the works for months in order to commemorate and take a stand against violence against women fell into the wider political conjuncture. Thousands of women took to the streets, and the colour purple – a global colour for feminism – was used as sign for the specific manifestation. The deliberate ubiquity of the colour in masks and ensembles mirrored the many ways in which aesthetics plays a powerful role in feminist and political attitudes.

In the past two to three years, like in many other places, feminism has made its way onto the cultural radar in Latin America, flourishing in Colombia as a significant trend. Women of all sorts have witnessed its momentum and blooming rhythms. Its inception and dispersion responds to a contemporary Latin American landscape in which the significant erosion of right wing, conservative movements have gained leverage in several countries, and it also responds to a wider global phenomenon in which feminism has become fashionable and in which fashion has absorbed feminism. This has unbridled substantial expressions in Mexico, Argentina, Colombia and Chile.

Colombia’s own current political climate echoes the Chilean one. Both cases render the structural wounds that Latin America has not yet healed. Abrasive inequality, social injustice, vicious corruption, precarious work conditions, insurmountable impunity, sex violence, the pains bred by racism and rampant classism – all are persisting marks of societies still acutely bruised by severe inequality in resources and opportunities. After signing a historic peace agreement with the continent’s oldest guerrilla group, Colombia has been restless in a path that speaks of reparation and peace. Discontent with the forgiveness granted to guerrilla leaders – some of whom currently sit in Congress, as a part of the deal – and a tenacious will from some social and political segments to implement the agreement unconditionally, all exacerbated a heated presidential election in 2017. Political identification with the left or right have became common in everyday jargon, and these dichotomies have spurred a bipartisan climate. Echoing the global mood, a fervent atmosphere of polarisation has settled in local debates. When the current president Ivan Duque defeated opposing candidate Gustavo Petro in a second voting round, divergence aggravated. The unresolved tensions and the clearing of the guerrilla armed forces as a predominant enemy have opened up the landscape to the structural wounds in Colombian dynamics. And last November, the country witnessed a state of unprecedented protest, with millions of people expressing discontent with the constant murder of social leaders in rural cities, economical policies, environmental measures, and a government that is being greatly challenged on many fronts. Social media, of course, has played a crucial role in stirring discontent and pouring it into collective, concrete demonstrations on the streets. After all, social protest may be one of the greatest societal trends in our current global cultural climate.

This fervent atmosphere has also been a vehicle for the politicisation of Colombian fashion in unprecedented manners. As it has become ubiquitous and accessible, it is also growingly questioned in more critical and uncomfortable ways. In the past half decade, Colombia has experienced an unparalleled boom as a country that produces interesting, covetable and known fashion. In this setting, fashion has acted as a cultural force, aiding in the reshaping and redefinition of long-held stereotypes that associated the country with violence, drug dealing and terrorism. The imagery produced in the past few years has created a strong sense of pride in wearing Colombian design. This is not insignificant considering that as a burgeoning industry, and like many other places in the periphery of the traditional fashion circuit, Colombians used to look towards the United States or Europe when it came to shopping and the legitimising of taste. Fashion has a funny way of performing as a simultaneous conduit of surfaces and depths. As feminism has eroded in the Colombian backdrop it has intersected with fashion (understanding fashion as an industry), and it has also become a fashion or a trend in itself. In this way, it has also sparked aesthetic expression, become a common subject in social media, and produced contemporary formats of digital feminism. It has also illuminated the different ways in which aesthetics can be materialised. The colour purple, the green scarves, the imaginative protest signs and another symbol, a raised fist, are all extensions of the ways in which feminism and aesthetics are currently entwined.

In the anthem sparked by the Las Tesis performance, dress is an important feminist expression. It also ties to something else: blame. Culpa. This is something significantly associated with what has been codified as feminine; something that is particularly exacerbated in spheres dominated by Catholic prisms and frameworks. In general, predominant understandings of the feminine have a deep-rooted history of blaming women for the ‘evils of the world.’ Judeo-Christian cultures are all connected by the ways in which femininity is subconsciously associated to mistrust and moralisation. We often find these ancient codes inscribed in the ways sexual violence is still interpreted. Blame and accountability often gravitate towards what the woman was doing, what she was wearing, to why she happened to be there in the first place. Still today blame is more often assigned to the victim than to the rapist. And in a continent that is predominantly Catholic, where the central figure women are taught to emulate is a virgin mother, an emblem of impossible purity, clothes and vanity, intertwined with the feminine, breed other concrete understandings of femininity. Catholicism believes in guilt: it moralises female sexuality, it condemns conspicuous womanliness, it makes women feel guilty for sensuous or free behaviour. Even if a lot of these societies have, theoretically, diminished the strength that religion used to have in shaping attitudes and behaviours, perceptive codes still bear the marks of these structural perceptions.

In many moments and places, feminism has also grappled with ideals of femininity, at times internalising its fabricated symbols in misogynistic ways, sometimes repudiating all things feminine in order to assert ‘true’ feminism. The connections between feminism, aesthetic expression and femininity have never been simple – and this complexity intensifies more so when it comes to the intersections between feminism and fashion. When seen in context, and in varying time frames, it becomes understandable and reasonable that as feminism battled to create unprecedented freedoms and rights for women, its acolytes would deem certain codes of the feminine – excessive ornamentation, subordination, dependence, prescript ways of being – as something that had to be rejected. It wasn’t until the eighties when more nuanced and critical views of fashion became available, with theorists and feminist writers arguing that concepts such as functionality and the natural – at times defended as necessary characteristics for a ‘freer’ sense of female dress – were also social constructs and had to be understood as social constructions rather than objective realities. They also pointed out that the negation of delight or pleasure in clothes and fashion as marks of ‘true’ feminism could be problematic and misogynistic as well. Additionally, as an industry, fashion has also been highly problematic in terms of manufacturing conditions, female exploitation, homogenising beauty ideals, classist concepts of taste, and bodily standards. As the views on fashion by feminist theorists became more complex, fashion began to be ethically questioned and today the interrogations fashion faces in terms of class, race and gender – to name just a few – have settled as general lenses to problematise its many fronts and nuances.

And now, there’s more. After the election of president Trump in the United States, multiple and massive women’s marches were unleashed, echoing those of the late sixties and seventies. Feminist slogans and symbols have become trendy, and ‘political fashion’ a sign of the zeitgeist. Recall Chimamanda Ngozi Adichié slogan ‘We Should All Be Feminists’ on a Dior T-shirt, the various attempts by magazines like Teen Vogue to acquire a politicised streak, or Karl Lagerfeld’s problematic 2014 theatralisation of a women’s march in the Grand Palais, for Chanel. As sociologist and fashion scholar Monica Titton writes, ‘not only has fashion embraced feminism, feminism has also become fashionable.’1 The Dior case was not an insignificant one, symbolically speaking, as Christian Dior’s iconic New Look represented, on some level, a sort of regression towards a certain type of femininity that rendered woman, as Simone de Beauvoir wrote, as a sphinx, an idol, and a thing.2) It’s never that simple. Already in the nineties, when the term ‘postfeminism’ was used frequently, debates about the commodification of feminism had already settled in the cultural landscape. This commodification is debated and problematised today for other, though similar, reasons. ‘As the example of Dior’s corporate feminist branding demonstrates, the ideological axis that has polarised feminism time and again became once more its relationship to capitalism and neoliberalism, which is why the relationship between the fashion industry (that is undoubtedly part of global capitalism) and feminism is inherently ambiguous and contradictory,’ Titton also writes.3

Feminism as fashion is not a statement that sits well with everyone. There is often suspicion when the two are combined in a single statement. Can fashion be feminist? Is it healthy for feminism to be fashionable? Fashion and feminism can be seen in a myriad of ways of course. It ranges from the ways clothes can reflect the ambivalence of freedom and oppression experienced by women in different historical moments and geographical contexts, to the ways in which writing about fashion can be a feminist endeavour. It includes the current scenario, where feminism has become fashionable and in which fashion, as Titton also points out, is going through an uncommon politicisation, expressing itself as a possible site for protest and dissent. This general ambivalence between fashion as a capitalist force, neoliberalism and feminism, expresses itself in an interesting light when it comes to Latin America, where a lot of feminist discourse can be strongly tied to leftist views.

Whereas in the United States for example there has been an aesthetic resurgence of the 1990s riot grrrl movement, Latin American feminism seems to be channelling its own sense of protest history. In Argentina, the green scarf, a light object that can be carried everywhere, worn around necks and wrists, is also a reminder of another form of iconic female protest, the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, a movement of mothers who campaigned for the disappearance of their children during the dictatorial regime, and who insistently pressured the government for answers between 1977 and the early 2000s. In Chile, ‘las encapuchadas’ refers to feminist women who wear hoods or capuchas, which is a Latin American symbol of insurgence, rebellion and ideology resistance by the left. These hoods or capuchas, once used by men resisting the dictatorial government, were typically worn in black to avoid recognition. Feminist groups today are, on the contrary, making the garment a site for aesthetic creativity and exuberance, using all sorts of colours, fabrics and textures. The hood is also a strong symbol for collective struggle: it seems to say, ‘your face is her face, your face is my face’ and it channels feminist practices, where individuality and shared experience combine. The colourfulness and variety of the capuchas today is a consequence of the current climate, making tangible a territory of resistance that is both physical and ideological. Punkish confrontation as feminist subversion is common when it comes to protest and public resistance.

Beyond all its ambivalence and contradictions, the intersections between feminism and fashion can also be read as another sign of our times: the inception and dispersal of what can be deemed as ‘the female gaze,’ which expands in all forms and terrains. The aesthetisation of feminist protest can be read as another expression of this gaze, in which structural transformation is also taking place in the ways in which the world, language, history, power, imagery, are increasingly narrated and seen from the feminine perspective and experience. Perhaps this is why one of the significant symbols of the current aesthetics of feminism, one that complements the colour purple, the green scarf, and fashion in general as a practice of dissent, is one that is neither object nor garment but a specific gesticulation: the raised fist. A fist balled up and held aloft evokes power in every shape and form, reminding us that dress, as a situated bodily practice, can also be a potent, recognisable and thrilling gesture: women raising their selves for revolutionary, ongoing transformation.

Vanessa Rosales Altamar is a Colombian fashion writer and scholar. She’s the author of Mujeres Vestidas, and is currently at work on her second book.

Monica Titton, ‘Afterthought: Fashion, Feminism and Radical Protest,’ Fashion Theory, Volume 3, Issue 6, Routledge, 2019, pp. 747-759. ↩

Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, Vintage Books, 2011 (1949 ↩

Monica Titton, ‘Afterthought: Fashion, Feminism and Radical Protest,’ Fashion Theory, Volume 3, Issue 6, Routledge, 2019, p. 752 ↩