These are times of post-truth, alternative facts and truthiness: at times it seems we are becoming fluent in Newspeak. But even as we have come to adapt to a more flexible view of reality, integrity, sincerity, truthfulness and authenticity remain consecrated ideals of selfhood. ‘Keep it real.’ ‘Stay true to yourself.’ ‘Be yourself.’ These truisms and tautologies have grazed many a coffee cup, self-help book and T-shirt, and they are a standard trope in TED Talks. Though we may cringe when we hear them, many of us have come to accept those corny phrases as conventional wisdom.

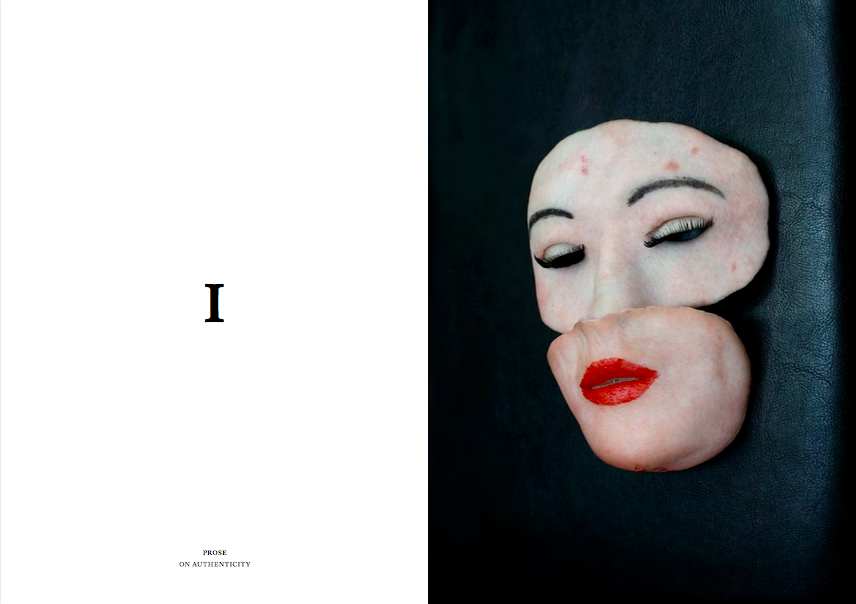

But is there such a thing as a ‘real me’ or a ‘genuine self’? How does one live an authentic life? And is it possible to do so in fashion, an environment so wedded to the mood of the moment, so seemingly dependent on masks and masquerade, adopted when convenient and shed when no longer useful. Some might say that fashion and authenticity are antithetical: one the definition of the present ethos, the other the value of those who strive to prevail over it. Or so an existentialist, smoking in Les Deux Magots in 1946, would have posited. Only by overcoming the accepted norms imposed on us by our social institutions – family, education, religion, government – can an individual begin to live a truly authentic life.

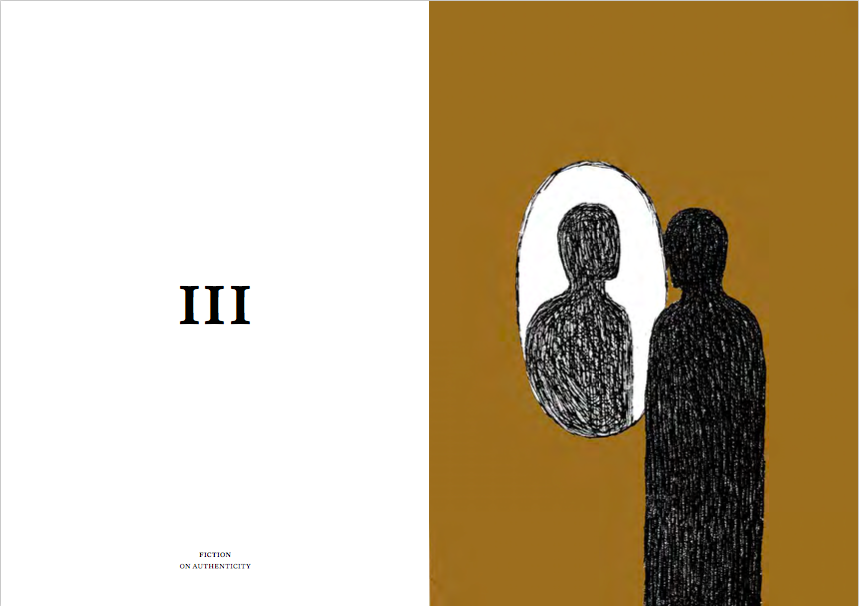

Today, philosophers prefer to think of authenticity as constructed and performed: we are selves upon selves upon selves. In 1981 Jean Baudrillard wrote about simulacra and simulation, meaning that we now have copies depicting things without an original. There is no more reality, only signs and symbols. Our experience of reality is only simulation; what it hides isn’t authenticity but that no such thing is needed for us to understand the world in which we live.

Curiously, as philosophers debate the collapse of authenticity in a postmodern world, in consumer capitalism it has taken on a supreme importance: in fashion it’s the holy grail. Terms like ‘artisanal,’ ‘heritage,’ ‘craftsmanship’ and ‘storytelling’ have become buzzwords, and conglomerates are fond of referring to their offices as ‘campus’ and co-workers as ‘family.’ The further away we feel from those values, the more important they become it seems. We speak of ‘real clothes’ as opposed to ‘fashion,’ and ‘real people’ as opposed to models.

We no longer live in tight-knit communities, nor do we work with our hands tolling the fields or making our own clothes. What we’ve gained in terms of a more fluid societal structure and in freedom of choice, we appear to have lost in terms of authenticity. We are nostalgic, yearning for a simpler, more honest time. We see it in our penchant for vintage clothing and all things handmade, and in the persistence with which fashion designers mine the past for inspiration. The aura of authenticity clings to this representation of an imagined past, but it’s never authenticity itself that we get – only an artificial and mediated spectacle.

In the 1960s the Marxist philosopher Guy Debord famously decried this ‘society of the spectacle,’ and fashion is a part of it particularly open to this type of criticism. Often dismissed as a theatre of manners, it’s typically singled out when we need examples of how mass media has turned everything, including reality, into a spectacle. According to this logic, the wistfulness we, in these unreal times, feel for bygone authenticity leads us to accept paying an ever higher price for something original, genuine, real – something authentic. We buy to help define who we really are – who hasn’t been party to the exclamation, ‘Oh, that’s so you!’ when trying on a particularly flattering garment? – but realness remains elusive and authenticity a chimera, and the products we consume never satisfy. And so we keep on buying, hoping that the next dress or jacket will finally prove our uniqueness and authenticity to the world. In the fashion industry, the rise of conglomerates and the ubiquitous branding and marketing that this has brought with it, has meant that authenticity is today often seen as manufactured, and therefore untrustworthy. Similarly, on the social media platforms today so popular within the industry and elsewhere, identity is generally understood to be constructed and performed. We know that the ‘realness’ signalled by hashtags and poses cannot be true or genuine. We see through it all, and then surrender in spite of it.

We want to believe. It’s curious that, how we can look at an image on Instagram – an artfully disheveled ‘influencer’ in the midst of performing the upward facing two-foot staff pose while wearing athleisure and sipping an organic green juice at sunset – and know that this image is the highly constructed result of a hundred discarded shots (we know, we do it too), while still being left with the nagging feeling that her life is better, realer, than ours. It’s this suspension of disbelief that keeps us in line, docile consumers, always striving for something other than we have. So that the day we too – fanning feelings of inadequacy in others – are pictured drinking hand-pressed squash in some exotic location, we allow ourselves to forget the effort we are constantly undergoing to ‘be ourselves,’ and give into the verisimilitude of poetic faith – a reassuring reward for the ‘authentic experience.’ On and on we go, ‘curating’ our lives.

What, then, represents authenticity in this era of simulacrum, when everything owes something to something else? We keep on keeping on, as the saying goes, striving to be original, though we know we will end up looking and acting the same. Advocating authenticity as a part of social life is, in fact, relatively new. The notion of the world as a stage, or ‘theatrum mundi,’ was expressed already among the ancient Greeks who saw the world as a sum greater than its parts, with people as characters and their actions as drama. And according to sociologist Richard Sennett, public life in early eighteenth-century Paris and London was also based on the doctrines and principles of the theatre. Being social meant making playful use of many masks, with little or no attention being paid to the personal qualities of the individual.

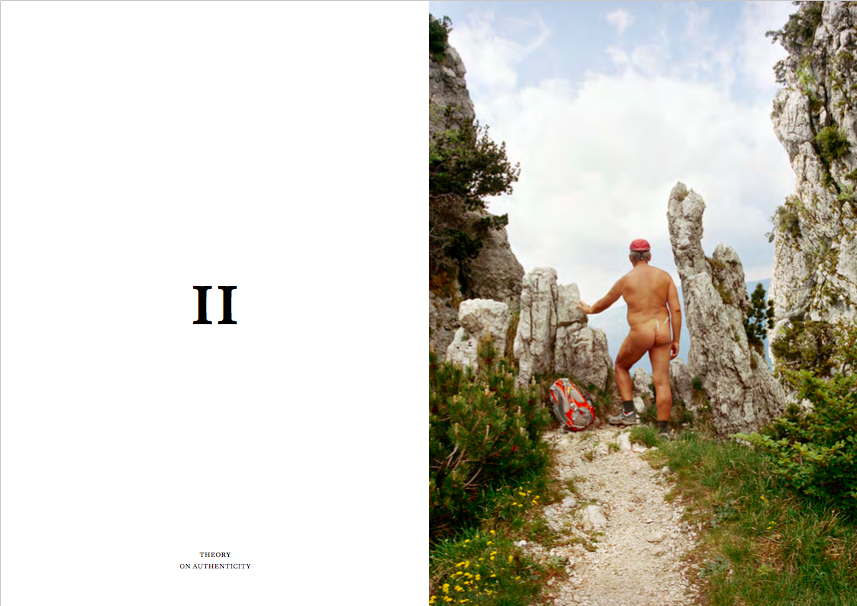

We are all actors, audience, observers and co-participants. Perhaps the idea of ‘staged authenticity’ or of social life as theatre, is less about seeing social interactions as an endless parade of interchangeable masks, and rather about making use of various personas, all equally valid. This is what sociologist Erving Goffman argued; social life has a front and back stage, and on both we perform. On stage, feeling self-conscious, we are aware of the machinations we employ. Back stage, we pretend not to be. But inevitably, we never stop performing. In other words, self-presentation, whether in person or online, is always a negotiation or dialogue between self-identity and the social realm. We consume, shop and get dressed in order to construct or enact an identity. Maybe, instead of the sharp line between ‘fake’ and ‘real,’ the multiple identities we perform every day are more akin to an endless dress rehearsal where no role, or persona, is more real or authentic than the next. We are lovers, friends, bosses, peers, professionals, parents and children and every role demands slight adjustments to its costume. For most of us, these roles are all real, and all performed. We conform, we rebel, we conform.

We offer encouragement to teenagers who experiment with characters – goth one week, valley girl the next – but tend to view those who continue their style experiments into adulthood with suspicion. Whereas we seem to have accepted that to be a teenager is to exist in a perpetual state of identity crisis, and that everyone in high school is to some extent putting on an act, as we grow up we’re expected to settle on one social persona, reflected in a consistency of appearance. But what if we were to abandon the idea that authenticity means consistency, and that masks are used to hide an inner self, and instead see every guise as valid as the next? There is nothing hidden behind the mask, the mask is all there is.

TEXTS BY

Laura Albert, Elizabeth Hawes, Lucy Ives, Alice Hines, Anja Aronowsky Cronberg, Eric Wilson, Jacque Mercer, Philippa Snow, Charles Baudelaire, Rob Horning, Rosie Findlay, Johannes Reponen, Andrea Kollnitz, Andrew Potter, Efrat Tseëlon

INTERVIEWS BY

Anja Aronowsky Cronberg

FICTION BY

Guy de Maupassant, William Thackeray

VISUALS BY

Torbjørn Rødland, Ed Templeton, Timm Rautert, Hans Eijkelboom, Mimmo Paladino, Aneta Grzeszykowska, Simon Menner, Roshan Adhihetty, Eddy Bofferio, Weronika Gęsicka

DESIGN BY

Studio Blanco