Hussein: It’s interesting that we’re supposed to talk about ‘slowness’. There’s a real nervousness in this industry – designers think that they have to reinvent themselves every catwalk show. I’ve been a fashion designer for over twenty years now and I find that attitude very tiring. It also means that the designer is always a bit too far advanced for their client, which isn’t really a good thing. What tends to happen is that people can’t relate to what you do, and you lose out.

Anja: Do you feel that you have lost out?

Hussein: Well, I always wanted my shows to be a cultural experience for the audience, but what ended up happening is that newspapers put, say, my bubble dress on the front page to sell more papers, and it would make people think that I was an ‘artist’, and not interested in making wearable clothes. But actually in the same collection I’d have long tailored coats, and the bubble dress without the bubbles and those garments never got any attention.

Anja: Do you still feel that this is the case, considering how fast information is now shared on social media and websites like Style.com?

Hussein: It’s true that with the advent of digital media people can see my collection before I’ve even packed my bags to come back home from Paris. On the one hand, this is great because everyone can see my work and I don’t need to rely on what the papers decide to publish in order to sell more copies. But on the other hand, the high street can also see what I do. I’m effectively giving my ideas away for free to other designers. The problem is that they can often do better versions of those ideas than I can, because they have the funds. That’s life though; you have to take the shit with the good, you know.

Anja: Am I right in assuming that you’re not a proponent of ‘democratic fashion’, or the idea that fast fashion is progressive design available at an affordable price?

Hussein: What happens today when high street retailers do ‘democratic fashion’ is that work like mine gets filtered. It’s true that it allows people who like designer clothing to buy simulations for a fraction of the price, which is good I guess, but it also means that I, and others like me, basically end up being designers for other designers.

Anja: What do you mean?

Hussein: My work is admired by the industry but it doesn’t reach the end consumer. Early in my career I used to think that it was okay to remain exclusive, to be a designer’s designer and perceived as ‘conceptual’. Today I feel differently. I’d like my work to reach more people, but it doesn’t because I’m seen as ‘too creative’ or ‘too conceptual’. All those stupid words; I find it very limiting.

Anja: Why is it important for you to reach more people?

Hussein: Well, to be able to do what I really want to do I have to have a bigger business. I want to be able to experiment more, to invest more in techniques and fabrics. Today, we have an okay business – it’s fine – but I think it could be much better.

Anja: Many of the designers I’ve spoken to mention that having their own store is an important step for a brand. You still don’t have one. What would opening a store mean for your business?

Hussein: If you don’t have your own store you rely on established conduits to reach the end consumer – buyers, reporters, stylists and so on. These people are fickle; they might like you one season and not the next. If, on the other hand, you have your own space you don’t need to depend on anyone. It’s hard to rely on press and buyers as filters for what you do, because if they decide that they don’t like you one season… then what do you do?

Anja: With that in mind, and considering that the fashion press is largely dedicated to advertisers today, how does someone in your position ensure that the press continues giving you the attention you need to appeal to consumers?

Hussein: It’s a difficult position to be in; I call it ‘the middle child syndrome’. I don’t have the buzz of being a young designer anymore, nor do I have the power that comes with being part of a big conglomerate. I’m in-between. I often wonder who’s really in charge of the great machine that determines what will be trendy next season, or who’s a hot designer and who’s not. I find that whole part of this business very peculiar. At the same time, being at this stage in my career, I understand better than ever who actually buys my clothes. If people really like what you do, they don’t care whether they read about you on Style.com.

Anja: You’ve mentioned a few times now that you used to feel flattered when the press called you a ‘conceptual’ designer, but that you now feel boxed in by the term.

Hussein: Now I find it annoying.

Anja: Could it be that the way the press defined you as a young designer was to your favour in that it helped mark you out, and contributed to the huge interest you’ve received from museums and the art world in general? And that the same label is today holding you back and making consumers think that your work is ‘too arty’ or difficult?

Hussein: I don’t believe in reducing a designer to any one thing. Categorising someone as ‘conceptual’ or ‘arty’ is just lazy and reductive. In fact, while the press was talking about me as ‘conceptual’ I was actually spending a lot of time making sure my sleeves and collars were perfect. The only reason I started sharing my creative process with the press was because they bloody asked me so they could have something to write about. If they think my process is too conceptual they can just appreciate the clothes. The process and the influences are there to help me create; the final result is what the customer will wear. That’s what really matters.

Anja: It’s as if you’ve been painted into a corner and now you’re stuck.

Hussein Maybe the mistake I made was that I should have spoken less about the collections and let the press and buyers enjoy the garments instead – you know, look at them properly, touch them, try them on. For two seasons I experimented with that approach actually. I didn’t do a catwalk show; I did a film instead and had the clothes in the showroom. And press and buyers came and touched the clothes. Those two seasons made a big difference I think. The people who came could see all the work that goes into each individual garment. For all those who insist on pigeonholing me as this ‘conceptual’ designer, it’s things like that that can make a difference. You know, this word conceptual – I hate it now.

Anja: There are a handful of other ‘conceptual’ designers who seem to be using the label to their advantage – Comme des Garçons perhaps being the most notable example. Why do you think it works for them?

Hussein: When they started the industry was quite different. They’ve been around a long time now, and with time they’ve become legends. They also have an amazing business model. They show a very directional collection on the catwalk and then have a huge amount of sub-lines and collaborations with which they can reach a great variety of clients. They have constructed a system where they can afford to do that. I can’t. I have one major collection, and I have to find a way to reach all my clients through it. This collection has to be both monumental and wearable at the same time, which is no easy feat.

Anja: You’ve said in the past that fashion now is not about creating something new – why has this changed?

Hussein: There is so much choice on the market today, so many designers and so many different styles. It’s all a bit diluted. I don’t think there is any one style or trend that dominates anymore. Today what’s making people look the same is plastic surgery, not clothing.

Anja: When you started out as a designer in the early 1990s, the age of the conglomerate wasn’t yet fully developed. Today being part of one is arguably how we define success for a designer. New products need to be generated constantly to ensure that the big companies can keep growing, and that their shareholders remain happy. What’s your feeling about this state of affairs?

Hussein: Consumers today are coerced to buy. We get things banged on our heads so many times via all sorts of media outlets that we end up getting used to, and then liking, things that we first thought were rubbish. Living in the age of consumerism means that the market needs us to never stop consuming. Like you say, big companies have to keep selling, or they’ll go out of business. We talked about ‘democratic fashion’ before – it’s a buzzword now. But is consumerism democratic? I don’t think so. It’s made to look like it is, but it isn’t. The system exists to make wealthy people ever wealthier.

Anja: The influence of big business in the fashion industry seems to have helped cement fashion as the perhaps most important part of pop culture today. You mentioned earlier how your most eccentric designs have routinely been placed on the front pages of newspapers in order to sell more copies, and we all know how important celebrity has become to fashion…

Hussein: We’re suffering from a design overdose right now. Being a designer has become fashionable. I don’t know any other business where a rich man’s wife can employ a team to work for her and declare that she’s a designer with no prior training. It cheapens our industry. Everyone wants to be a designer today, whereas I’m thinking, ‘Do you even know what it takes?’ Think about it. You have to have something different to say, you have to have a market. Designers have to run a business; we have offices and employees. Stylists can work from their house and charge a load of money. Photographers work from their computers when they’re not shooting in the studio. Designers have to run businesses; those guys run themselves. You can quote me on that. I don’t think consumers know how designers really work. They think it’s glamorous. Actually our lives are difficult. A lot of people give up when they realise how difficult it is.

Anja: Which is why longevity is so…

Hussein: Important?

Anja: Noteworthy.

Hussein: Yes, and it’s also really important to know who you are as a designer. I’m lucky enough to know my style by now. I’m a compositional designer.

Anja: What does that mean?

Hussein: It means that I draw compositions. I have rules; my methods and ways of working are quite developed by now. I’d rather do what I know well than try and change all the time. When I was younger, I explored a lot and each collection ended up looking quite different. In retrospect, I think it confused my buyers. They must have been wondering what to expect from me now.

Anja: We talked earlier about the speed of information sharing on the internet. How do you feel that this has affected the way we work?

Hussein: The abundance of information that we have today lowers the appreciation of it. We don’t have time to stop and read anymore. Everything has to be quick now. Fashion attracts a lot of really insecure people. A lot of people in the industry suffer from what I call ‘BBD’ – Bigger Better Deal. You know when you’re at a party, talking to someone and they’re looking over your shoulder to see if there is someone else more important around the corner? I’ve met a lot of people like that, people whose eyes are constantly wandering. So many people in fashion are afraid of missing out.

Anja: Considering the abundance of designers on the market today, what does it take to stand out?

Hussein: Fashion is about loving what you used to hate and hating what you used to love. It constantly changes. I think that the people who do well in fashion are the ones with really strong opinions. People with strong opinions are believable, regardless of whether they’re right or wrong.

Anja: I see what you mean – especially considering that fashion people are often accused of being turncoats.

Hussein: When you actually come across someone that does have an opinion, they’re respected – even even if it’s a crap opinion.

This article was originally published in Vestoj On Fashion and Slowness.

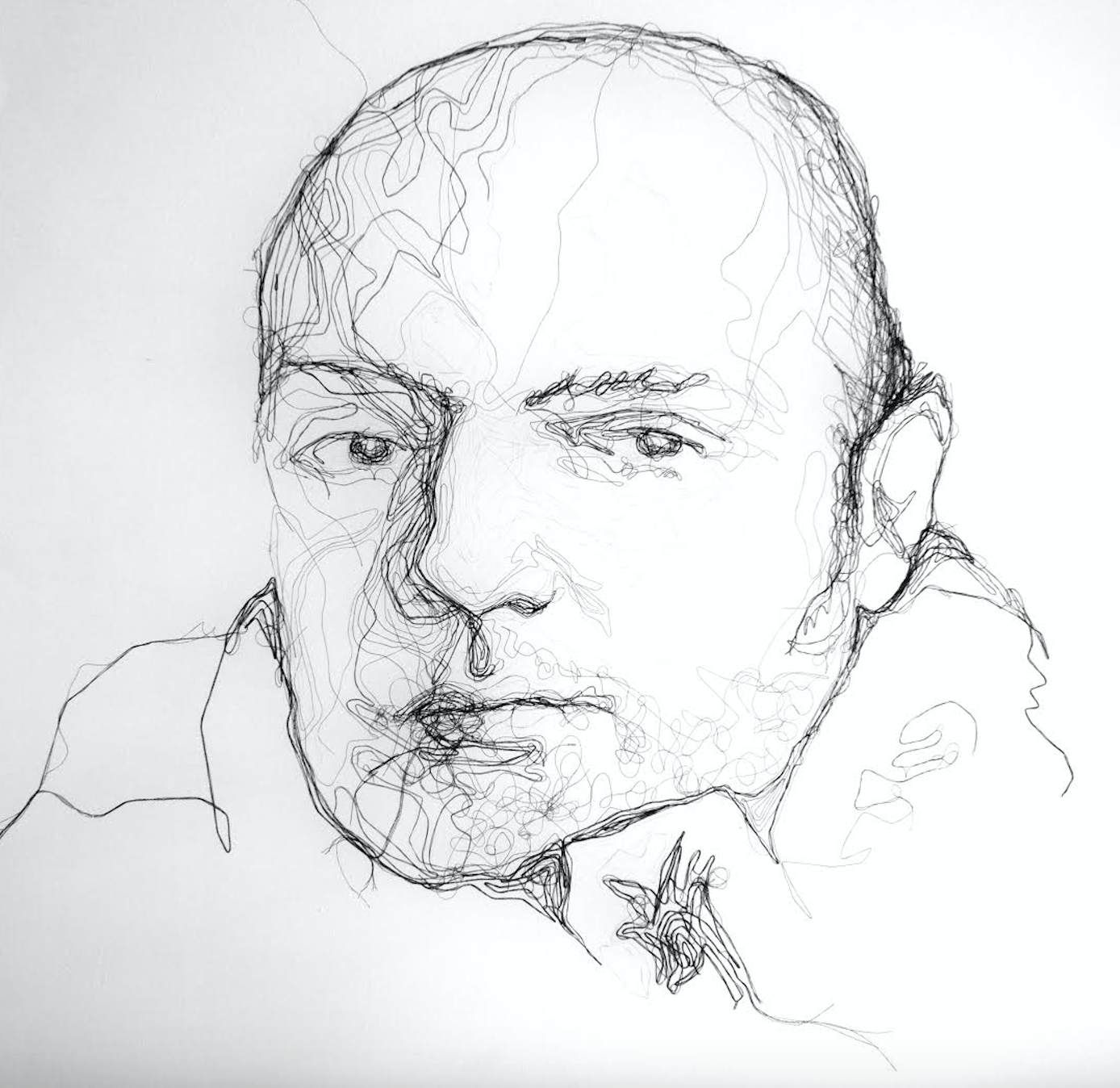

Louise Riley is a London-based textile artist and illustrator.

Anja Aronowsky Cronberg is Vestoj‘s Editor-in-Chief and Publisher.