THE DISCOURSE ON CLASS mobility is pervasive in contemporary India, and is in itself seen to be one of liberalised India’s greatest fruits. In particular, the public imagination often portrays creative professionals as fuelled by drive and ambition (above anything else) and thus capable of rupturing historical boundaries of class and caste thanks to this imagined innate power. However, while this myth continues to circulate within Indian fashion and other creative industries like it, we continue to see certain consistencies amongst top designers in the industry – while indeed many of them embody great amounts of talent, they are also overwhelmingly from upper caste and middle to upper class backgrounds. They are also likely to run their brands with the help of their families, and articulate their privileged ‘backgrounds’ as necessary for their success: ‘backgrounds’ refer to both healthy, pre-existing financial safety nets and/or vehicles that produce ‘taste,’ or what is more commonly articulated as ‘good aesthetics.’ These aspects separately, or together, link up to what it takes to be a successful designer in India. However, a close look at the fashion education reveals something noteworthy: none of these aspects, that are synonymous with success, are acquirable through a fashion education which is still promised as the main inroad.

As part of my fieldwork for my PhD dissertation in anthropology on Indian fashion (2012-14), I attempted to understand the making of the Indian fashion designer: a professional identity that was crafted during the wake of India’s liberalisation reforms in the mid to late 1980s. Key to crafting this identity was its antithesis: the tailor (or darzi) who while historically dedicated to the production of clothes was always seen as ‘unprofessional’ thanks to the lower caste/class position he occupied. Investigating fashion education was a key part of this research, and to explore my questions about class mobility in the creative industry, I spent a few months doing participation observation at National Institute of Fashion Technology, or NIFT, Delhi – India’s top fashion university, which was established in 1986. This was followed by new research in November/ December of 2018, during which time I re-visited current and ex faculty in the Fashion Design department who have associated with the institute for at least two decades.

NIFT Delhi has since its inception been considered the nation’s best fashion institute. It is centrally located in an upper middle class neighbourhood and is marked by its innovative, open-plan architecture. At NIFT, Fashion Design is one of the institute’s most coveted courses, with room for about thirty students across India each year; Garment Manufacturing and Fashion Marketing follow this. The fee for these courses is approximately 1.10 lakh rupees a semester (approx. USD 3100).1

At NIFT Delhi I attended a pattern making class a few times a week, and spent time with fashion students outside the classroom as they would try to make sense of what they were learning in class versus their own ambitions, ideas of success and imaginations of the ‘Indian designer’ identity. What I found was while most middle and upper class Indians would consider NIFT to be a well established, respected and funded institute that trains students for jobs in fashion (particularly in retail which continues to be the biggest employer of NIFT students, post graduation), the aspirations of students – usually the more successful ones – are mixed, although dominated by the desire to begin an independent label. However, because this ambition is only reached by a handful of students, I suggest that there is a need to reflect on the relationship between the representations of Indian fashion as glamorous and a vehicle for class mobility, versus the very real obstacles that students face and that are seen as optimistically surmountable by an undefined quality that is glossed as ‘drive.’ I argue that despite the attempts to democratise fashion – which has led to the opening of sixteen NIFT campuses across India – the education system continues to benefit those who come from a ‘good background.’ However, the faculty continue to express ‘drive’ as the single, most important asset that leads to success, and thus put in their best efforts to shape talent when they spot it.

To introduce this argument, I begin with a summary of an excerpt taken from my fieldwork notes in 2012. Although this fieldwork is about six years old, I will go on to explain its continued relevance in the contemporary context:

I was observing a class taught in the Fashion Design department one afternoon. It seemed fairly regular until the professor, Varsha2 asked the students to gather around her table for a ‘special discussion.’ In front of her she had spread open a copy of the Times Of India, with a huge section of the newspaper outlined with neon highlighter. The attention-demanding title read: ‘No More Bling Please: Says Sonia Gandhi.’ The article featured a full speech delivered by Sonia Gandhi, the [then] leader of the Indian Congress Party, following her visit to NIFT’s newest campus in Raebareli [which is classified as a Tier 2 city in Uttar Pradesh].

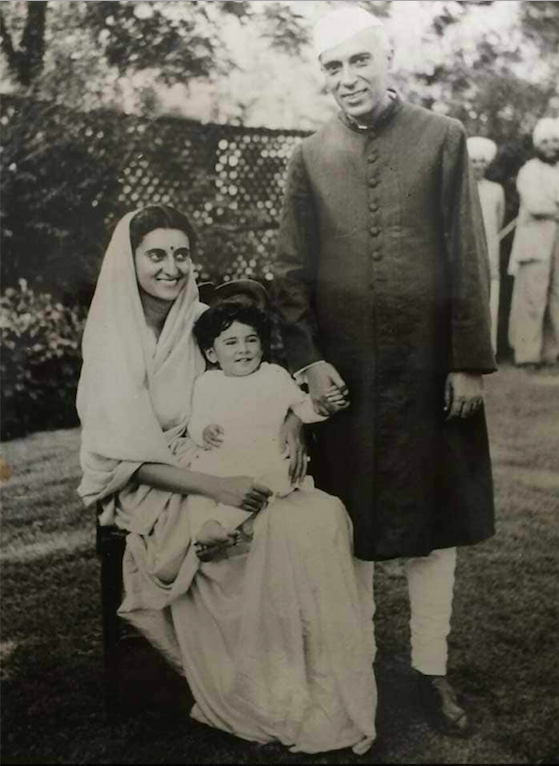

As the story reported, during her opening statements Gandhi pleaded with student designers to stop making ‘bling,’ which she equated with ‘adding more (surface) ornamentation to a garment.’ Citing her mother-in-law, Indira Gandhi, as the ultimate ‘style icon,’ Sonia Gandhi who the article reminds us is of ‘Italian origin’ explained that she ‘preferred the simpler saris that showcased India’s textiles’ and encouraged fashion students to ‘work more closely with the craftsmen’ as they developed their careers.

This article served as the point around which the main lesson of the day would be crafted. Varsha used the article to assure students that the training that they were receiving – a decidedly anti bling, ‘professional’ fashion course – was something that Gandhi ostensibly supported. ‘Now you all understand? Even your future leaders are telling you to listen to your ma’am instead of doing just bridal stuff.’ She made an implicit connection between ‘bling’ and bridal ‘stuff,’ and re-instated her own position against it, thus revealing her politics in the process.

An interesting dialogue followed. Tarveen, a young woman in her class asked: ‘But ma’am how come then, all the Indian designers who are making bling are selling well?’ Many other responses that questioned the discrepancy between what was portrayed as ‘success’ and what students were learning in class, followed.

This ethnographic excerpt reveals how the NIFT – an educational centre that marked the birthplace of Indian fashion – becomes an important platform upon which to map class difference and privilege. While the goals to professionalise middle class designers and democratise fashion remain the superficial mandates of the post-liberalised educational institute, representations of famous designers, as Tarveen points out, are associated with a strong career in bridal wear which is de-linked from the skills that are directly cultivated at NIFT. Alternatively, success can also come from ‘good aesthetics’ or ‘drive’; the first is a synonym for cultural capital, which is de-linked from bling, while the latter represents an ability to tap in to, or overcome, markers of this privilege for those who are not born in to it. The point is that neither can really be taught, although efforts to move closer to Indian textile production which for many faculty represent ‘good aesthetics’ have been encouraged: ‘one of the most refreshing changes in the last few years is that our students are now seeing the value of Indian craftsmen,’ Mrs. Bani Jha, a faculty member, explained.

However, even through there may be an active ‘Indianisaiton’ of the syllabus (through say, expanding the courses on Indian textiles), bridal wear – which is touted as the bread and butter of the industry to the point of fatigue – is still seen as a low hanging fruit by most faculty because of ‘its reliance of surface ornamentation rather than actual garment manipulation,’ Jha explains. Thus, students who come to fashion school to ‘make it’ in a traditional sense, and are bereft of both abundant financial capital or the usual markers of taste, can be left quite disillusioned: while their education can often give them a deeper, holistic understanding of fashion and confer upon them a range of skills that may make them skilled designers, it does not necessarily secure their futures, or prepare them to be successful entrepreneurs given the current landscape of the fashion industry.

Karan Parmar who attended NIFT in the early 2000s, reflects on his education as ‘a wholesome one,’ that ‘was set up for a life that could take you anywhere.’ He remembers his professors (including Mrs. Jha, cited above) as ‘excellent teachers,’ who effortlessly translated their training from the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York (where all NIFT’s initial faculty were trained to lay the blue print for NIFT’s initial syllabus) to an Indian context. However, when I ask him about what the education did for him and his career, his lens is less rose-tinted: ‘I, of course, being from a good background was okay, and could take joy in studying something like costume and art history… I was lucky to have gone to NIFT. But, did the education directly prepare me to be a successful fashion designer? No.’ His conclusion has to do with the fact that in his perception, education does nothing to prepare students for the reality that marketing and media exposure – most accessible through bridal wear designers – is not something one can get through going to a good school. Parmar today runs a successful, small-scale flower business. He recalls that out of his batch – a class of thirty – only one or two are perhaps doing what was considered ‘the NIFT dream’: setting up an independent label. When I shared this insight with a current faculty member however, she noted: ‘Yes it’s true that most cannot set up an independent label (in fact we do not encourage this, straight out of college), but some of my richest students have gotten nowhere in the industry…. It’s all about the drive.’ For her, the students she chose to talk about as shining examples were the ones who were able to cultivate a full fledged business through developing Indian textiles and ‘modernising’ craft (i.e. examples that showed skill versus ornamentation) and barring Sabyasachi (arguably India’s top designer), none of the ex-students she named were associated with bridal wear.

Not all alumni are as generous as Parmar in their recollection of NIFT memories. When I made my interest in fashion education known to some of my ex-informants, I was contacted by Divya, a twenty-seven-year-old NIFT graduate who has gone on to become a leading designer at a major international company. For Divya, who describes herself as ‘thoroughly middle class,’ and ‘in need of a sustainable career post education,’ she thinks of her time at NIFT as quite antithetical to her success. ‘What NIFT prepares you for is an export job (i.e. a job in a garment industry) that pays some 20,000 rupees (approximately USD 300)… that is not what most my friends I went to fashion school for,’ she shares. She recalls most professors as ‘behind the times’ and the discourse around fashion ‘dated, boring and limiting.’ This is largely because of its lack of focus on the international market, global trends, and networking opportunities outside of retail or export/buying houses. For Divya, her success was based on intuition. She credits it to the idea of ‘knowing the limited value of a degree.’ She states: ‘I knew to stay a little quiet (despite being on probation) and play by the rules.’ For her, a fashion education is summed up as a necessary formality, but definitely ‘useless’ for anyone who does not have class privilege to supplement it. ‘I wish fashion school would teach you how to network, or give you opportunities to network… and even tell you that bridal wear, no matter how gross it is, is important,’ she says, coming to head with the question of what matters, and the essential steps she took to get to the position she now finds herself in.

Thus, what Parmar paints as the ‘mixed ambitions and results’ honed at and by NIFT, is for Divya ‘a randomness in education.’ Both also recognise that this is possibly due to the decline of the institute in recent years, which they suspect the quality of students accepted also contributes to. Unlike in the early years, where admissions were very competitive, and included an interview that is recalled by faculty as challenging, today students are accepted more loosely (based on a portfolio) and are placed at any of the sixteen main NIFT campuses across the country. Thus, for both graduates and many others, the ‘democratisation’ of fashion is in many ways directly linked to an exacerbating quality. Another current Professor who has been teaching for more than thirty years echoes this point: ‘in the beginning, our students were very, very serious about fashion… today, I have some [female] students who are here just to wile away their time before they get married and sit at home,’ she says. Thus, there is a link between a perception of decline in education as part of a larger decline in the idea of the industry at large.

My recent visits to NIFT echo my findings in 2012. While a group of highly dedicated faculty – many of who have played a big part in honing the skills of India’s top talents – continue to teach with passion and focus, the institute remains one of the key ways in which class differences are reproduced. To date, the idea of introducing pattern making for bridal wear remains a near joke, and even surface embellishment for that matter – which is the marker of valuable clothing in Indian fashion – remains a course that one student describes as ‘by the way,’ i. e – not crucial.

The ideals of pattern making, Indian and Western, continue to be taught, and what is imagined as a holistic education continues to be imparted on to students. For students with pre-existing class privilege who are able to then use education not as a ladder for class mobility, but a supplement, fashion school is a good idea. However, for students from less privileged backgrounds these programs are both less likely to lead to success as they imagine it, and are all the more important. In sum, for those students who still associate fashion school with success, the very idea of success needs to be deeply nuanced. This nuancing, however, is itself a privilege.

Meher Varma is a cultural anthropologist based in New Delhi.