In the three simple and, in retrospect, very carefree years I was married without children, I would often, without meaning to, draw comparisons between myself and my father, which – as I constructed them – I could not live up to. Pappy is old enough to be my grandfather. Born black in the segregated South in the 1930s, he did not know his own father, and as I realise now, he got his ideas of masculinity freestyle, from the books he read and the movies he sat through, from the uncles who showed him from an early age how to box and throw a football, and from his own highly particularised code of honour. No one showed him, though, and he did not try to learn, many of the things my friends and I spend a lot of our time doing: talking about our feelings, changing diapers, fixing the family supper. Nor would any of us have wanted him to. He was a serious and busy man, busier than I think I have ever been and somewhat frightening – and he was a provider. Never a rich man, I have only come to see in adulthood some of the small pleasures Pappy withheld from himself so that we might take them for granted.

Pappy kept one of those nylon shoe racks hanging on the back of his bedroom door. Most of the surface area, and then some, of the single story house we lived in was occupied by floor-to-ceiling bookshelves that stored the thousands of volumes of literature and philosophy and management strategy he’d used to climb up out of Texas, but here, in my eyes, was the real treasure. When he was out running errands or working in his study, bent over a book or teaching the students who filed into our house to sit with him and fix their test scores, I’d slip into his bedroom and rifle through his belongings: fingering his penknives and leather-strapped watches, feeling the soft silk and woven wool of his neckties, inhaling the funky, wonderful smell of his aged leather belts – which I handled with a mix of awe and fear, the two or three times I behaved very badly, these doubled as instruments of punishment – and studying that weathered, bizarre source of power, his wallet.

But on the back of his door, in front of that nylon shoe rack, is where I always found myself standing, pulling down the enormous neon yellow and gray Air Maxes (shoes roomy enough I could stick my own sneakers into them), the perfect ecru Reeboks, styles which have come and gone many times, as well as the oxblood Alden lace-ups, the mahogany Cole Haans and the sleek black Ferragamos (the only Italian shoes he could countenance), designs that have never been outmoded. These latter pairs are the ones that, on early Friday and Saturday evenings, the times he was not working, usually after showering and shaving and putting on whatever it was he had that smelled so amazing, I would find my father in his bedroom with his grease and his brush and his rags steadily polishing, the football game or the tennis match flashing in the background. I’d come in the room and he’d greet me warmly but without stopping. He polished and cleaned all of his real shoes carefully, just as he folded and hung his slacks and his blazers as soon as he undressed, never leaving them to pile up on a chair and get wrinkled. Pappy didn’t ever speak about fashion, but I could tell even then how much care he put into the few things that he was wearing. What I couldn’t realise, not at that time, was how old these items were, that my father had stopped buying things for himself, almost entirely, as long as I’d been living.

My brother is five years older that I am. For as long as I’ve been conscious of it, whenever his feet grew I too would receive a new pair of shoes. Maybe it started when I was in fourth or fifth grade. I’d noticed a new pair of blue-and-white Air Flights on his feet, box fresh, with the orange-and-gray Nike Air tag still affixed at the lace hole, as was the style where we grew up in the early Nineties. I must have thrown a jealous tantrum, but Pappy, a well-groomed man who cared – but not overly – about how he looked and probably, now that I think of it, might have enjoyed a vacation, remained impassive. He didn’t scold me. My brother and I were sitting in the backseat and when we reached our house he kept driving. Pappy drove us all the way to Foot Locker, where he bought me an equivalent pair of Nike Air sneakers. I’m certain he couldn’t afford them. I’m ashamed of the amount of Air Jordans he has since bought me. Yet from that day on, whenever either of our feet grew, he took both my brother and me shopping.

I think I was afraid to become a father myself because I could not imagine I could make similar sacrifices. The memory of, on warm summer evenings, coming back home from the basketball courts to find my father hunched over his shoes, working them to a brilliant polish, is one of my fondest. This is how a man is: a man works; a man uses what he’s got and improves it; a man knows and understands the value of a thing, and he knows its price is not always synonymous; a man also spends a real sum from time to time – as was the case with those Aldens – but with discretion, only when it’s worth it.

It has been a long time since my feet grew several sizes larger than Pappy’s, and I couldn’t even pretend to squeeze into his Air Maxes. I’ve developed my own tastes, too, having grown fond of the kind of Italian loafers he detested. I’m slimmer; I almost never have use for a belt. In many respects, I think it’s too late for me to learn to move through the world the way my father did, and I think, on a certain level, that is what he worked so hard for. But I’m a father, too, now. I cook and I clean, I change diapers and my wife and split the expenses. My close male friends and I get together over glasses of Pauillac and tell each other about our fears and ambitions. I need this. I know I could never be the kind of solitary rock that my father was, but we are not entirely dissimilar, either. For one thing, over the years I’ve bought a lot of my own shoes, and some are expensive: glistening black A. Testonis for my wedding; Dior Homme patent leather lace-ups; suede Fratelli Rossetti loafers I found on sale in Naples; burgundy desert chukkas from Church’s; many, many pairs of Nike Air Maxes; now I laugh when my almost three-year-old daughter attempts to wear them. What she doesn’t realise – and it’s fine by me if she never does – is that, some time ago, I also stopped buying new ones.

Thomas Chatterton Williams is the author of Losing My Cool and Self-Portrait in Black and White, and has written for The New Yorker, Harper’s, and the London Review of Books.

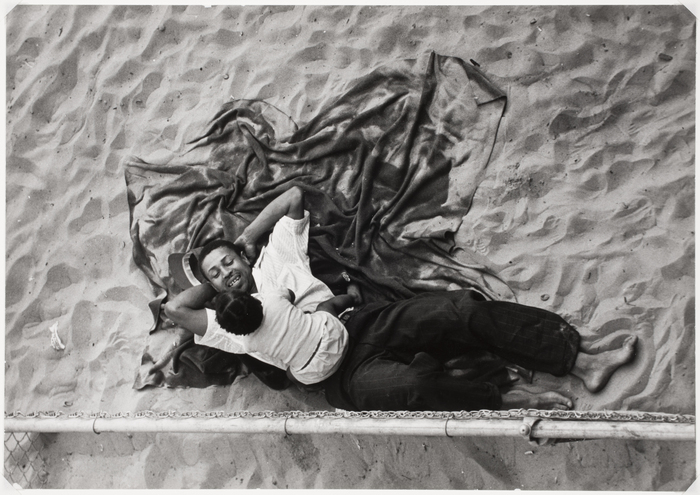

All images courtesy of the International Center of Photography (www.icp.org).