This article is the first in a series of interviews about dressing in monochrome.

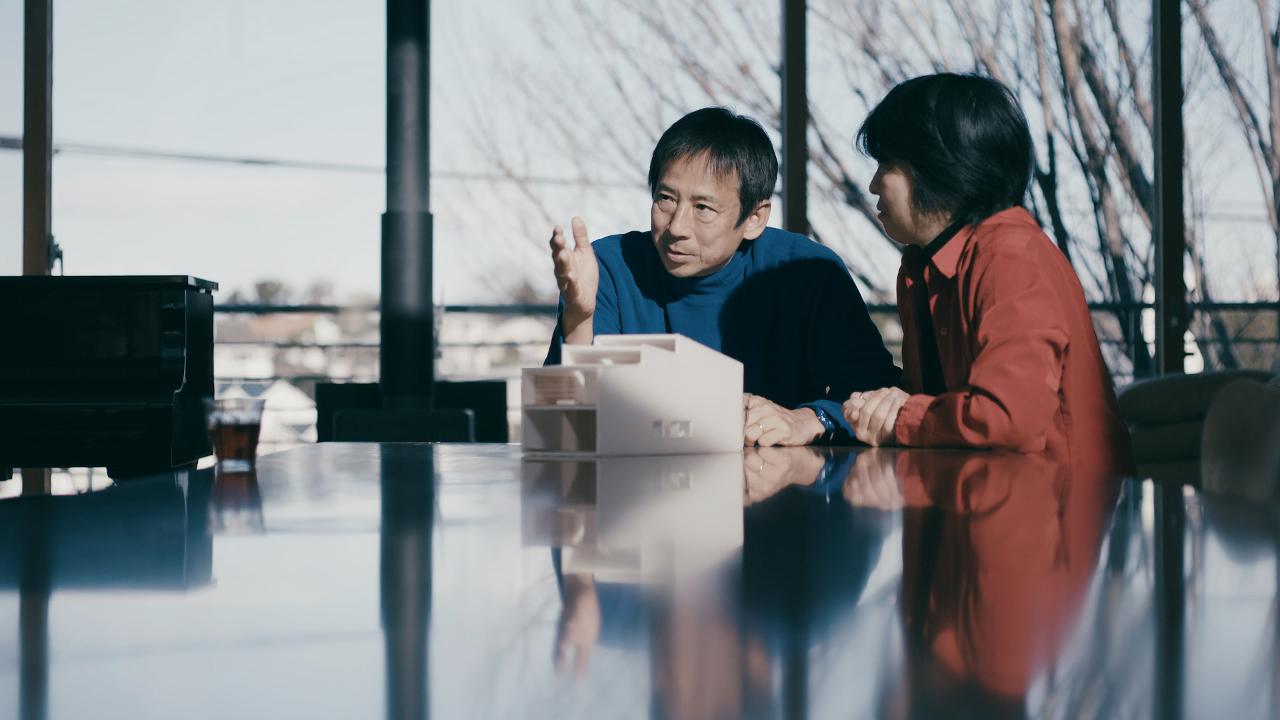

ON THE FRONT OF Tezuka Architecture’s catalogue of work, the names of the firm’s principals, Takaharu and Yui, are written in contrasting colours: blue and red. Recently, I spoke to them in their home in Tokyo, Japan, via video call. It was a warm spring evening here, in New York City, and a bright morning there. As it happened, they were similarly arranged: Takaharu, on the left, in his signature cobalt, and Yui, on the right, in a cherry shirt that that looked plucked from the primary colour wheel.

Yui and Takaharu’s designs feature almost no colour. One project, the Roof House, is all sandy wood, topped with a sloping gray roof (each family member has a personal skylight, through which to ascend to the outdoor space). Their ‘Wall-less house’ has a ground story that’s entirely glass, filtering in whatever colours happen to be outside on the trees and in the sky. In their own lives however, colour is a defining characteristic. Yui wears almost exclusively red; Takaharu blue. The objects they share (car, furniture) are yellow. Their daughter, fourteen, wears yellow, too; their son, eleven, wears green.

Alice: What were some of your early relationships to colour?

Takaharu Tezuka: It started from red.

Yui Tezuka: I loved red since I was very small. It suits me. And I didn’t wear pink. I guess pink is a symbol for girls, but I didn’t like it. Eventually, I quit wearing different colours and decided to wear just red.

Takaharu: I’ll tell you more. I used to work for an office called Richard Rogers’ Partnership. Richard Rogers is the architect who designed the Pompidou Centre and Lloyd’s of London. At that time, Richard Rogers was wearing blue. And everybody in the office was trying to wear blue, because everyone wanted to be like him. Richard Rogers himself didn’t like that solution. So he changed the colour to shocking pink, so that nobody could follow. But still, we stayed in blue.

And then, in 1992, I got married with a lady in red all the time. So eventually it became red and blue. And so, then, when we came back to Japan we found a car. A car in yellow, the yellow Citroën Deux Chevaux. And then, we decided that everything we have in common would be yellow. So that is how it started. It became certain in 1994, when we started our business in Japan.

Eventually, we had a daughter. That was much later, in 2002. And then because everything we share is supposed to be yellow, we made her into yellow. Still now, she loves yellow. Three years later we got a son. We were supposed to make him into yellow as well, but my daughter didn’t like to lose her colour. So she said, let’s give him green. Now we’ve got four colours.

Alice: What were their reactions as they got older? Do your children ever want to change their colours?

Takaharu: I think they’re quite happy about it.

Yui: Yeah. My daughter is quite happy about it. She doesn’t want to wear or have anything except yellow now.

Takaharu: And my son, he’s still wearing green. He doesn’t hate it. But he’s not as fond of green as my daughter is of yellow. But recently we bought a green suitcase, and he loves it.

Yui: Because my daughter is always wearing yellow, when she was in nursery school another child’s mother started to give me yellow clothes. When the mother bought yellow things to give her son, he didn’t want to wear it because it was the colour of our daughter.

Takaharu: And in class, everything yellow belongs to her. So she always gets a big portion, because many things are yellow. She gets a collection. And no one in the class wants to wear yellow, because it’s her colour.

Yui: It’s quite fun. Each of us having our own colours makes us have some kind of identity. I think it’s good. Makes our life easy and more fun.

Alice: Do you wear these colours head to toe? Or do you mix them with other colours?

Takaharu: Red, blue, red, blue, yellow, green – it doesn’t mean that everything is this colour. Underwear is white. [Laughs]. If everything is blue it becomes crazy!

Alice: Where are each of you from? I read your parents were architects.

Yui: I grew up next to Tokyo. And my father is an architect, and I grew up in a house which my father designed. I loved that very much. So I began to have interest in architecture. I decided to become an architect when I was sixteen.

Takaharu: I also grew up in Tokyo. And my father is an architect too, but working for big companies. And on both sides, my grandfathers were architects. Mother’s side, he wanted Frank Lloyd Wright to design his headquarters, but actually Frank Lloyd Wright was too old already. So he had to ask his apprentice to design his headquarters. We are very much a designer’s family.

Alice: Do your children want to be architects?

Yui: My daughter used to say she wanted to be an architect but she decided not to become that.

Takaharu: Yes, still!

Yui: Still, yes, there’s still some interest. But now she’s saying she wants to be a graphic designer.

Takaharu: Recently, a few years ago, she won a competition for school emblem. And the emblem is printed onto all kinds of cans, bags, everything. And she says she became proud of her graphic design.

Alice: I’m curious about how you two work together. What’s that process like?

Takaharu: We actually don’t separate projects. We do everything together. And ok, I do understand the structure aspect of architecture more. And I’m very good at drawing and making models. And my wife is very good at precising the models. So I work first, make it, then she comes with the knife and she cuts to the model I designed carefully. She gets a red pen and makes corrections on my drawing. That’s what she’s very good at.

I think it’s quite important to work together. If I’m alone I can’t decide if my design is the objective. But the way we work together we can make sure this is right or not. It’s a natural feeling. And working together helps that understanding.

Alice: Does colour play a role in your designs?

Yui: We don’t use colour for our architecture because… how should I say it? The colour should be added with people.

Takaharu: We consider architecture as a kind of platform or a dish, for a nice cuisine. And if the dish is too colourful the cuisine doesn’t look good. So that’s the background. Architecture is quite the basic, natural colour.

Yui: In our lives, colour comes from us and also some things we pick like sofa and bed and accessories.

Alice: In any of the spaces you designed for others, have the people who inhabit or work in them adopted your philosophy on colour?

Takaharu: There are some families, for instance, one family who is in stripes all the time. But that’s nothing to do with us. They had that sense before they met us. So I don’t think our architecture changed their lifestyle. Our design is not to change, but to enhance their lifestyle. But maybe the stripes did become more consistent, after they met us.

Alice: Can I ask about any favourite coloured objects of yours?

Takaharu: A watch! It’s called a Swatch. I like this watch because it’s so basic.

Yui: I like dry material for T-shirts, that’s easy to clean. This shirt is my favourite. When I order, I order like, thirty or forty shirts of this.

Takaharu: For anything I like, the design must be simple. We say we’re like a dog. He’s always wearing the same thing. And in winter, our fur gets a little longer, so we’re wearing a sweater and jacket. And then we take it off, and inside is always the same as the summer.

Alice: How does a simple lifestyle impact your day-to-day routine? Or translate into other areas of your life or work more generally?

Takaharu: To separate the washing – it’s quite easy!

Yui: I don’t need to worry about what to wear every morning.

Takaharu: And the other thing is that people remember us quite easily. Even at my daughter’s school, they know me by colour. Blue father and red mother. And ok, our daughter is yellow. People want know more.

Takaharu: It’s the same thing as in this interview. People are curious.

Alice: What do you think the relationship is between clothing and architecture in general?

Takaharu: I can’t answer the question really, because architecture is a background. It’s better to be natural. But there’s one thing I can say. Architecture should be simple but at the same time it should be lively. So architecture is not black and white or red, often it’s neutral. The brown is natural. Sunlight coming in is cheerful. And in that way, it’s always written who lives there.

Yui: Our architecture has a kind of openness, to the environment. And to the people inside. All the rooms of the people inside can feel the openness to the people next to them and also to the nature.

Alice: If you didn’t wear blue or red, and you had to pick another colour which one would you pick?

Yui: If I have to quit my red? It’s quite difficult to think about. If I had to quit the red.

Alice: So you can’t think of one?

Yui: No, no.

Takaharu: Same me.

Yui: But when I don’t have the red shirt, when I feel cold, sometimes I wear blue.

Takaharu: I give her a blue sweater sometimes.

Alice Hines is Vestoj’s online editor and a writer in New York City.