The seventh issue of Vestoj, ‘On Masculinities,’ is in stores this month. In conjunction, Vestoj Online is publishing a series of articles on the same theme.

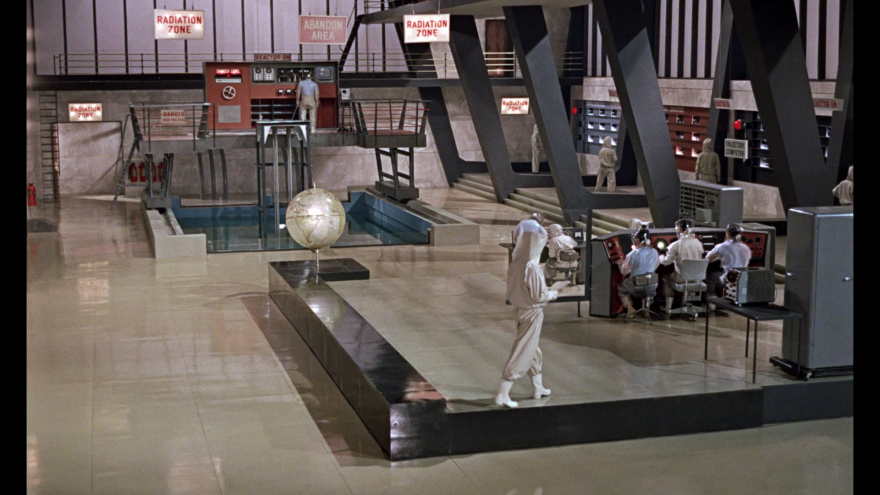

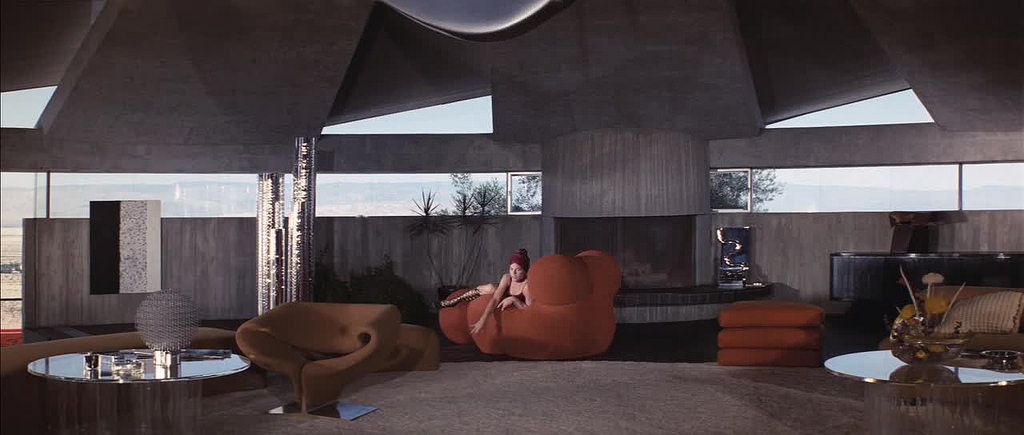

THE FIGURE OF ‘JAMES Bond,’ created in 1953 by novelist Ian Fleming and translated to the screen ten years later, has lost none of its potency. The spy with expensive, sophisticated tastes – and the income needed to satisfy them – still appeals strongly to the popular imagination. The ‘Bond’ films are noted for their overall stylishness – the award-winning sets, the credit titles with their New Bauhaus input in the early years and, of course, the suits. In 2012 the Barbican Centre in London commissioned a substantial and successful exhibition ‘Designing 007: Fifty Years of Bond Style;’ it has been touring the world ever since. In 1987, however, media sociologists Tony Bennett and Janet Woollacott had speculated about the possible future of the franchise.1 But as the same decade brought about both a revolution in menswear and the creation of a market for male ‘grooming products,’ the well-dressed spy survived. The following two decades prolonged his life much further, through the growth of ‘brand recognition’ and the worldwide marketing of European luxury goods; both now accompany, and in part finance, these films.

There is nothing on ‘Bond style’ within fashion scholarship, despite the innumerable academic interventions over the last thirty or more years. But Bond has been saluted as icon of taste within the pages of men’s magazines since his inception; in the run-up to the release of the latest film, Sam Mendes’ Spectre, GQ published a series of special issues. However, this essay will suggest that in recent years there has been an undermining of Bonds’ style – and even the actual cinematic narratives themselves – as product placement and commercial partnerships threaten the autonomy of both costume designer and director.

Bond was very much a creation of the 1950s – a decade marked at first by austerity but which saw economic expansion, full employment, and new patterns of spending. Fleming directly appealed to his male readers’ fantasies and gave them guidance as to how they might use their new disposable income by describing in careful detail Bond’s every change of dress: the shirts, the ties, the shoes, the casual outfits, the expensive fabrics and muted colours. He also offered them the hero’s endless womanising and his successful bedding of desirable, equally well-dressed women – which continued on screen, though there the women were by contrast scantily-clad, and which has interestingly been rather restrained during Daniel Craig’s current stewardship. All this helped to foster the relationship between Fleming, Bond and Playboy magazine, first published in the very year of Bond’s debut. As film scholars Pam Cook and Claire Hines argue, its admiration for both Fleming and his hero was not only a part of ‘the consumerist, sexualised and liberated lifestyle that it promoted;’ it was also because the magazine took men’s fashion very seriously.2

The meticulous but understated style which Fleming portrayed so successfully was carefully recreated when the first film was made in 1962. Cultural historian Christopher Breward addresses Bond’s cinematic incarnation and sees Sean Connery’s Savile Row suit as a ‘vessel for aspirational promise.’ Connery, he argues, had an ‘everyman’ appeal, while his ‘reticent machismo offered the ideal mannequin around which Fleming’s discreet indications of flawless style could be dressed.’ He notes, significantly, that his suits were notable for ‘resisting the flamboyance of fashion.’ Connery’s suits, as Breward tells us, ‘adhered to the pared-down rules of the guardsman and changed little over the course of the six Bond films he made before 1971.’3

In the 1960s, decade of social change, actors, musicians, writers and cultural entrepreneurs from traditional working-class backgrounds enjoyed unprecedented success; this led to media claims that the country’s rigid class barriers were coming down. Connery himself was a Glaswegian bodybuilder, a former milkman, model, lifeguard, and lorry driver. Fleming in fact wanted the more patrician David Niven, while the producers favoured the ever-elegant Cary Grant; initially worried about Connery, he gradually came to accept him. The film’s director, Terence Young, took Connery to his own tailor for Bond’s screen wardrobe. This was part of a Pygmalion-like process: ‘he took him to dinner, showed him how to walk, how to talk, even how to eat.’4 There is an apocryphal suggestion that when the suits were finished, he told Connery to wear them all the time and even suggested that he should sleep in them, so that he might cease to be aware of their presence.

The ultra-conventional dress of this hero is very much at variance with the popular image of the 1960s, favoured in the mythologising of the era, which tends to emphasise youth, stylish subcultures, new music and changing fashions, in a way that as revisionist historian Dominic Sandbrook has shown, is not entirely accurate.5 Nevertheless, there were undeniably new and radically different models of masculinity which emerged during this contested decade. Marcello Mastroianni’s memorable portrayal of a cynical journalist in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita arguably inspired the ‘mods,’ with their sharp Italian tailoring, to wear black shirts under white suits. The Beatles favoured suits that were very different from those of Bond, and boys copied their long, floppy fringes, and the dancer Rudolf Nureyev and the Rolling Stones created newly androgynous modes of masculine dress. Mick Jagger famously wore a Grenadier Guards jacket to perform on television in 1966, thus sending large numbers of young men off to the shop I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet in Carnaby Street where he had purchased his own.

Bond, a staunch defender of Armed Forces and Empire, and Connery himself were both antithetical to and horrified by these developments. In Guy Hamilton’s Goldfinger from 1965, Bond tells the villain’s secretary, Jill Masterson, ‘My dear girl, there are some things that just aren’t done…’ such as ‘listening to the Beatles without earmuffs.’ Connery stated in an interview for Playboy that he himself did not like the Beatles and so approved of the line. He had in fact kept very quiet about the fact that he had modelled for the mail-order catalogues produced by the gay men’s boutique Vince while looking for acting jobs in London; author Fleming would have been appalled. Both writer and actor were probably horrified by the ruffled lace cravat worn by Connery’s successor, George Lazenby, in a nod to contemporary fashion. It was this, perhaps, that tempted Connery back for another appearance.

Roger Moore, who then took over for twelve years, imbued the role with overdeveloped humour and playboy behaviour. He eschewed Savile Row classicism and followed fashions: wide ties, flared trousers, conspicuous lapels. His interpretation of the part – and the films themselves – have an element of pastiche; he began his Bond career in 1973 by jumping lightly from crocodile to crocodile in Live and Let Die. His films showed no awareness of the shifts in gendered behaviour that characterised the next two decades. His replacement, Timothy Dalton, did seem to acknowledge change; he was far more serious – and soberly dressed. He was the first to embrace Italian tailoring as did Pierce Brosnan, who took over from him in 1995 and whose interpretation of Bond involved a good deal of deliberate, studied charm. Judi Dench, who took over as M, was unimpressed, telling him in one scene, ‘You’re a sexist, misogynist dinosaur, 007.’

Daniel Craig, Bond since 2006, perhaps listened and certainly provides a Bond who in many ways is quite different. He gives the first convincing, complex portrayal of the conflicted masculinity of a hired killer who must do his job, but who is not lacking in sensibility; he is even capable of falling in love, of feeling loss and betrayal. It seems the Vatican itself has noted these changes; their newspaper L’Ossera Romano praised 2012’s Skyfall for its new, introspective Bond, ‘less attracted to the pleasures of life, darker and more human… even able to cry – in a word, more real.’6 This new reality is combined with a physical strength and muscularity which make him seem – like Connery – worrying capable of carrying out the killings which his rank in the service demands.

The posters for Craig’s very first Bond film showed his dinner jacket hanging open, his black tie undone and flapping, while the black-and-white pre-credit sequence was a mix of cinema verité and film noir, partly shot in a shabby public lavatory. The credits of Spectre are a lavish and dramatic contrast; against a backdrop of molten gold, a line of dancers part to reveal the gilded, perfectly-proportioned and splendidly-muscled torso of Craig, posed as classical hero. A girl stands on either side; when his shoulders are stroked, small flames erupt. Craig’s body-as-spectacle, waxed and buffed, is an integral part of the reinvention of Bond and provides an interesting contrast with the extravagantly hairy body of Sean Connery. In Casino Royale, Craig’s first outing as Bond, it is the splendid body of the hero – and not that of a Bond girl – which rises Venus-like from the waves, a deliberate reference to Ursula Andress’ famous emergence from the sea in Dr. No. Now, it is the body of Bond at which we should ‘look’7 – while on a more mundane note, the La Perla swimming trunks he wears here were located instantly by fans and London stockists swiftly sold out.

If the figure of Bond is now openly the object of a homospectorial gaze, Craig and the scriptwriters also acknowledge the homoerotic potential of the series. Skyfall introduces Bond – and audiences – to a new, young Q, with rumpled hair and fashionable parka. He is played by openly gay actor Ben Whishaw, and wears sweaters by Missoni, Dries van Noten and Prada. In the same film, Craig himself responds almost flirtatiously to villain Javier Bardem’s stroking of his chest and thighs; when he says, ’What makes you so sure this is my first time?’ he seems almost to shock the bleached-blonde uber-terrorist, who moves back to the safety of his laptop.

By some terrible irony, it is this complicated and sometimes sombre hero whose style is compromised by commercial imperatives and the vagaries of fashion. In Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, protagonist Cary Grant had shown how classic Savile Row tailoring could survive even a chase through the dusty fields of the Midwest while under aerial attack. Connery always managed similar feats, in the suits created for him by Antony Sinclair, whose name did not actually appear in the cinematic credits. And so too did Craig on his very first excursion, when he was immaculately attired by Italian tailor Brioni. However, in the last two films he has been dressed in the ultra-fashionable suits of Tom Ford, now one of the four major sponsors of the franchise; Jany Termime, the costume designer, works alongside him. At the time of Skyfall, Ford’s jackets were a generous hip-length, and Craig tended to unbutton them so that he might maintain his dignity while in pursuit of his adversaries. But by the making of Spectre, fashions had changed and his suits with them; the jackets were now shorter and much narrower in cut. So sadly, in the action sequences the agile Craig looks as if he might burst out of the same skimpy suits at any moment; audiences fear for him, but it is a sartorial mishap, a split side seam, that they worry about, rather than a properly-aimed bullet from one of his adversaries. Nevertheless, Ford’s later designs have featured heavily on the many blogs and websites that now exist solely to describe and display the latest clothes and accessories seen in the films.

Despite their appeal to audiences, these particular, high-fashion suits arguably disrupt the proper operation of the narrative. In 1998, film scholar Stella Bruzzi famously argued that with costume on screen, there is always one vital question – do we look at or through the clothes?8 If we look at the clothes, the cinematic flow is disrupted – not desirable in an action film. But here, we cannot help but be distracted and are forced to look at the too-tight suits and the obtrusive details: the noticeable sunglasses, the shoes with their fashionable ‘monkstraps,’ the tight white dinner jacket Craig wears in Spectre which is far less flattering to him than the discreet black Brioni one he wears in Casino Royale.

In a new millennium, Bond is faced with many difficult tasks; these have included parachuting into the London Olympics beside the Queen as well as taking on multinational crime syndicates headed by shadowy constantly-morphing villains. Now it seems he may have to fight battles and companies much nearer to home, if he is to preserve his own stylish image. There are other threats to the franchise. Spectre was filmed in Mexico, and a government anxious to improve its own public image offered generous tax cuts; this lent a whole new dimension to the notion of ‘product placement.’ Most disturbingly, there is the threat of a new, bland Bond. Craig, the first actor who has imbued the part with the complexities of fraught modern masculinity, has announced that he may retire from the role. The candidate suggested as his most likely successor definitely lacks the depth of the current incumbent; Bond could become a mere clotheshorse, the films a parade of suits and sunglasses.

Pamela Church Gibson is Reader in Cultural and Historical Studies at the London College of Fashion, University of the Arts London.

T Bennett and J Woollacott, Bond and Beyond: the Political Career of a Popular Hero, Macmillan Education, London, 1987, p.295 ↩

P Cook and C Hines, ‘Sean Connery is James Bond: Re-fashioning British Masculinity in the 1960s,‘ in R. Moseley (ed.) Fashioning Film Stars: Dress, Culture, Identity, BFI Publishing, London, 2005, pp.147-160 ↩

C Breward, The Suit: Form, Function and Style, Reaktion Books, London, 2016, p.197 ↩

B Macintyre, For Your Eyes Only: Ian Fleming and James Bond, London, Bloomsbury, 2008, p.205 ↩

D Sandbrook, White Heat: A History of Britain in the Swinging Sixties, London, Little, Brown, 2006 ↩

L’Osservatore Romano, Wednesday October 31st, 2012 ↩

See L Mulvey, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,’ in Visual and Other Pleasures, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009 ↩

S Bruzzi, Undressing Cinema: Clothing and Identity in the Movies, London, Routledge, 1997 ↩