AT A TIME WHEN Givenchy’s creative director Riccardo Tisci can claim one million followers on Instagram, puppets of Karl Lagerfeld are available for purchase and celebrities build fashion empires, this series looks at designers’ public personas as branding mechanisms and sites for discussion in fashion.

While fashion designers today reach the heights of celebrity status, the roots of the phenomenon lie in fin de siècle intellectual salons in Paris, where fashion first became an autonomous discourse and a vehicle of contemporaneity.1 As popular haunts for bohemia and artists alike, literary salons favoured the cult of personality and, along with parties, performances and gallery openings provided artists with the opportunity to socialise with peers and potential buyers. Thus, the successful management of public personas became crucial. This new necessity also reflected a shift in the production and dissemination of art. Its creators were increasingly forced to embrace democratisation and to negotiate their position within mass culture. Suspended between pure creativity and commercial demands, fashion assumed centre stage.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, mass consumption and new forms of mediation and promotion meant that authors, artists and designers had to engage with a sophisticated system that on the one hand promoted the cult of the individual, but on the other catered to a broader audience than ever before. As literature scholar Rod Rosenquist points out, the key genres of literary modernism – the Bildungsroman and the autobiography – all suggest a close link between modernism and celebrity culture.2

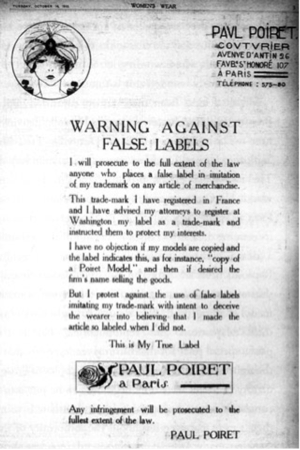

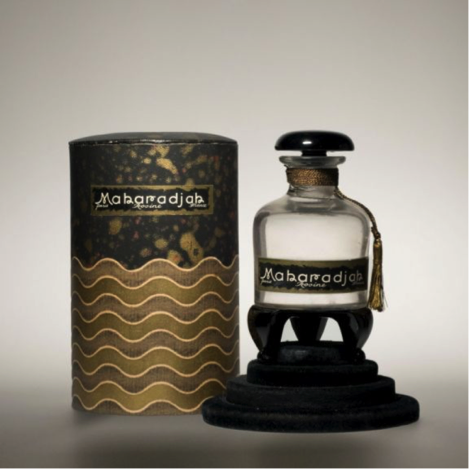

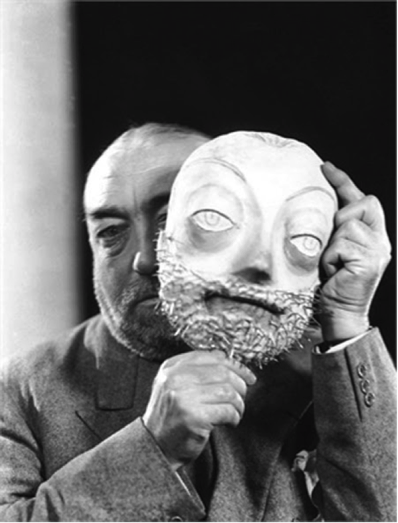

Paul Poiret was one of the first fashion designers to understand the power of a well-crafted public persona. Patron of the arts, legendary party host, chief promoter of Oriental taste, costume designer, allegedly the first fashion designer to free women of corsetry. He was also the first couturier to create a signature fragrance and venture into furniture design; Poiret owed much of the success of his enterprise to the promotion of himself as a brand.

Not surprisingly, he was also the first fashion designer to write an autobiography. A highly subjective genre, the autobiography allows its author to perform their self on the page by combining history and fantasy. Fashion editor Diana Vreeland called this mix of facts and fiction ‘faction’.3 She herself employed this rhetorical device throughout her life, most notably in her own memoir D.V. (1984), whose title references her flamboyant, adventurous persona as fashion editor for Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue.

Poiret’s autobiography was published in three volumes: En Habillant l’Époque (1930), Revenez-y (1932) and Art et Phynance (1934). Only the first one has been translated into English with the title King of Fashion (1931), which since became Poiret’s nickname in the American press.4 The books came out at the time when Poiret – whose fashion house had closed down in 1929 – was a ghost of his former self in the public eye. On the brink of poverty and largely ignored, he was eager to have his voice heard and secure his cultural legacy.

Poiret’s memoir follows the traditional chronological order of autobiographies. As the reader discovers the author’s childhood, it is immediately clear that Poiret’s performance in the text is based on his identification as an artist, rather than a dressmaker:

‘I am told that one of the first words I uttered was: ‘Cron papizi,’ and the initiate understood that this way of asking for a pencil and paper (crayon et papier). Thus, my vocation as a painter revealed itself before my vocation as a dressmaker; but my earliest works were not preserved – they seem to have had no interest or meaning save for myself.’

King of Fashion: The Autobiography of Paul Poiret, by Paul Poiret, 2009

Poiret then proceeds to recall his early sensitivity to colours, exquisite smells and beauty, as if in retrospective he could foresee his career as designer and parfumier. ‘Inspired by the brilliance of flowers,’ he writes ‘I tried to make inks and colours […] Or else I wanted to extract the perfume from the roses, and I confined them in bottles of alcohol and soda water.’ At the age of twelve his vocation as designer manifested itself: ‘Did I already dream of stuffs and chiffons? I think I must have. Women and their toilettes drew me passionately.’ Such descriptions evoke Poiret’s future predilection for Orientalist fantasies and also establish his persona as ‘artist of the cloth’, thus validating fashion as a discipline worthy of intellectual pursuit.5 By underlining the inherent importance of the toilette, Poiret also seems to echo Honoré de Balzac’s famous claim ‘La toilette est l’expression de la societé’ (the toilette is the expression of society),6 The discourses of fashion and art often overlap as the designer shares anecdotes about his collaborations with Paul Iribe, Georges Lepape, Raoul Dufy and Georges Barbier.

Throughout his memoir, Poiret draws heavily upon the motif of the misunderstood artist. In doing so, he positions himself within the eighteenth and nineteenth century tradition of ‘great men’ whose work was misjudged by the audience.7 He addresses this conflict explicitly while discussing the work of painter Raoul Dufy, who designed stationery and textiles for the house of Poiret. However, it is clear that the designer is indirectly talking about himself in the passage:

‘For an artist the useless is more precious than the necessary, and he is made to suffer when people try to make him admit the inanity of his daring, or when only that which is saleable is chosen from his work. An artist has antennæ that vibrate far ahead of ours, and he has presentiments of the future trends of taste long before the vulgar. The public can never say that he is mistaken; it can only express humility, in matters it cannot understand.’

The motif of the misunderstood artist is balanced by another literary topos, that of modesty, which shows the designer’s familiarity with the genre. Yet his desire to establish his cultural legacy surfaces again, accompanied by a critique of the minimalist, streamlined modernism represented in the Thirties by Coco Chanel:

‘People have been good enough to say that I have exercised a powerful influence over my age, and that I have inspired the whole of my generation. I dare not make the pretension that this is true, and I feel, indeed, extremely diffident about it, but yet, if I summon up my memories, I am truly obliged to admit that, when I began to do what I wanted to do in dress-designing, there were absolutely no tints left on the palette of the colourists […] I am truly forced to accord myself the merit of all this, and to recognise also that since I have ceased to stimulate the colours, they have fallen once more into neurasthenic anæmia.’

The designer’s tone and persona convey a sense of nostalgia for a time where his creative output was in tandem with the zeitgeist. His desire to shape Parisian cultural life with his ideas may appear self-aggrandising, but it also reflects the utopian spirit behind the ideal of the total work of art. He writes, ‘I dreamed of creating in France a movement of ideas that should be capable of propagating a new mode in decoration and furnishing.’ An admirer of the Wiener Werkstätte, Poiret did believe in shaping everyday life as aesthetic experience through clothing, craft and art.

Poiret’s articulated performance of the self in King of Fashion offers multiple readings. It is first and foremost an attempt to articulate his cultural legacy and situate himself in history. It also parallels the modern conflict between art and commerce perceived by many designers and artist, a condition enabled by the increased privatisation of the practice and experience of art. But the significance of the text today, at a time when fashion seems consumed by an obsession with heritage and branding,8 is that it provides a privileged, nuanced perspective into the origins of contemporary celebrity culture.

Alex Esculapio is a writer and PhD student at the University of Brighton, UK.

N. Troy, Couture Culture: A Study in Modern Art and Fashion, MIT Press, Cambridge, 2003. ↩

R. Rosenquist. ‘Modernism, Celebrity and the Public Personality’, Literature Compass, Volume 10, Issue 5, 2013, pp. 437-448. ↩

Quoted in Lisa Immondino Vreeland’s documentary The Eye Has To Travel, 2011 ↩

P. Poiret, King of Fashion: The Autobiography of Paul Poiret, V&A Publishing, London, 2009, p. 153. ↩

C. Breward, Fashion, Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 2003, p. 103. ↩

quoted in V. Steele, Paris Fashion: A Cultural History, Berg, Oxford and New York, 1988. ↩

T.B. Porterfield and S.L. Siegfried, Staging Empire: Napoleon, Ingres, and David, Pennsylvania State University Press, Philadelphia, 2006. ↩

Paul Poiret’s global trademark rights and archives were recently sold to Shingsegae International, already a partner of Céline and Givenchy among others. This is one of the many recent attempts to resurrect historical fashion houses. See http://fashionista.com/2015/08/paul-poiret-resurrection. ↩