This article is based on a multi-sited ethnography with proprietors of everyday high-street launderettes with garment alteration and shoe repair services in a multi-racial London locale, my own neighbourhood of close to two decades. Flipping between theory and life writing through autoethnography, this project blurs the boundaries between work and (my) home, revealing how repair can be a generative lens to reappraise the skills, value, and agency of these workers.

I read repair as a transient craft practice in order to visiblise the embodied dimension of repair-related work, foregrounding both cognitive and creative skills that are omitted in the binary in fashion between ‘knowledge work’ and manual labour. Secondly, repair explores the inherent sociality of repair work, its function deeply embedded within a community of use, and the affective dimension of nostalgia. Finally, repair as responsibility invokes a reading of radical care and is a reflection of my interlocutors perceptions on the value of their own work through the prism of immigrant family businesses, characterised by an intersection of obligation, independence, and pride.

I’m sitting with Moshda after-hours at the dry cleaners she owns with her sister. In between her stories, she pauses intermittently to let me write notes. She also stops to adjust the small space heater on the shop floor towards me and implores me to drink my tea and eat from the plate of biscuits, dates and sponge cakes she has laid out in my honour.

She tells me stories of how as a young girl in Afghanistan, she’d sit and keenly watch her grandmother at home on her sewing machine. It sparked Moshda’s interest in also learning, not to necessarily become a tailor (the term she uses over the pointedly gendered ‘seamstress’) but to acquire the skills in creating something from nothing. One of her grandmother’s creations, a green fitted dress with a matching blazer that had yellow diamonds hand stitched onto the lapel, stands out in her memory: ‘As you are asking me now I can see it in my mind. I remember her making it and I remember her wearing it one day, she wore a pair of dark sunglasses with it.’ Moshda speaks with zeal in describing the talent of her grandmother creating full outfits, particularly suits, from scratch, regularly for herself and often for other family members and customers. ‘If you can make a suit you’re an expert tailor. Dresses, skirts, things like that are easy to make; a suit is more complicated.’ Moshda’s interests are closer to the making of garments rather than their repair, saying she prefers ‘bigger projects’ over the alterations that make up her regular day-to-day work: ‘If you have fabric and you start a garment, it can be whatever the customer wants. If it’s their garment, it’s really limited.’

Moshda poignantly traces how the genealogy of a garment functions as a vehicle to understand how her own embodied skill emerges and can perhaps be best utilised. An early interest of mine in studying garment repair is close to this conception. I wanted to understand how a repair person situated their own agency or creative skills in relation to these often simple or mundane alteration requests. I inherited a ‘crude Marxism’ to paraphrase the anthropologist Daniel Miller, in a discussion on the analytic of production. As I conceived it, as the repair worker is not the garment’s original producer but is rather involved in service work, the transience of the exchange and the object’s state is similarly unstable which renders the process a form of double alienation.

Yet Moshda went on to reveal a far more attentive lens to think about her work. She explains she begins every task contemplating, ‘What can I do for this person to make her comfortable in this dress?’ Far from mundane or routine, alteration for Moshda is a critical process connected to the satisfaction of her customers in both a commercial exchange and more pointedly as an intimate process related to bodily aesthetics and the wearer’s self-esteem; ‘If they go somewhere else and a person makes a mistake they will end up wearing something that’s not right.’ Her skill and reputation are at stake in every request, necessitating a far more engaged role than the prism of double alienation allows us. Rather than abdicating this responsibility, she embraces it: ‘There’s no second chance for this person.’ She describes instances of customers believing that a garment needs one thing, but in observing the dressed body, she diagnoses something else entirely. This expertise in seeing garments from the technical perspective of a craftsperson, assessing how it hangs or fits the body during her consultation process whilst simultaneously troubleshooting, pinning fabric and proposing a path forward led her to tell me: ‘If I do alteration, I’m part of it, I play a part in the garment.’

*

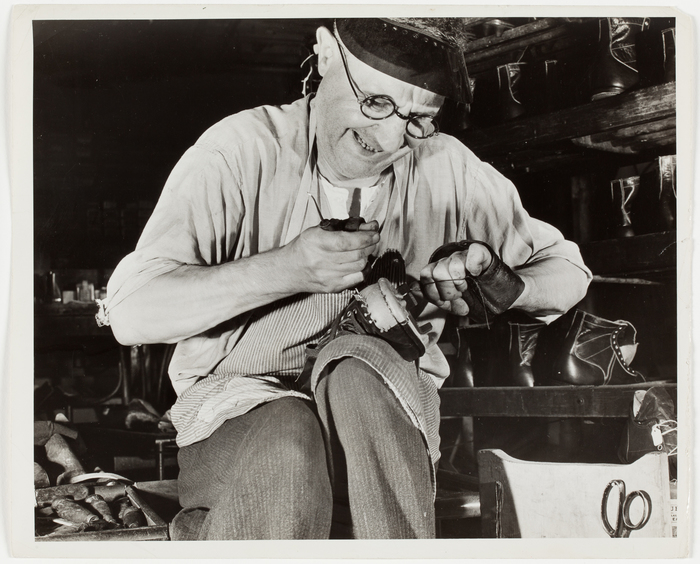

At the shoe repair shop, Nick indulges my curiosity to watch him at work. Born to Greek Cypriot parents who emigrated to the UK in the 1950s, Nick’s father was a chauffeur and his mother a seamstress. He speaks of their relentless hard work to make a life in London; ‘[They] never had a day off, you know, usual stuff,’ implicitly recognising my understanding of familial sacrifice as a fellow child of immigrants. His father-in-law, the then proprietor of the shop, handed the business over to him in 1988, imploring him to have ‘something for yourself’ and teaching him the requisite skills. Nick is affable and talkative and spends time demonstrating his work to me. ‘You’ve got to have a good eye and you’ve got to have a steady hand. I suppose because I’m using the knife a lot. Trimming rubbers and leathers. Don’t cut your fingers off or your chest you know, because you’re working like this towards your body,’ he demonstrates by holding a shoe and a small cobbler’s knife horizontally towards his chest.

Occupying one of the walls in Nick’s shoe repair shop is an assortment of black and white photographs of surrounding local areas to the shop, most of them gifted to him by customers who know of his fondness for local history. He says about the photographs; ‘I like these old areas. I mean old footage of Camden Town, ‘cause I grew up in Chalk Farm when I was a kid, I used to live opposite the Roundhouse and you know, you go there now, it’s completely different to when I was growing up. And I see old photographs, sometimes I say, oh look, that’s my era, you know? And now it’s changed. So I like all this.’ Nick’s images date back to the 1900s, and a few of them are of the same road that the shoe repair shop is on. Nick points out a number of roads and buildings in the photographs, motioning for me to look out of the window and explains where they are in relation to where we are standing.

The shoe repair shop opened in 1959, yet since his tenure in the late eighties, he made a series of changes to maintain his livelihood. In the nineties, he introduced key cutting services, now an integral offering in the majority of garment repair shops. He says ‘It was a sideline because my father-in-law was only doing shoe repairing. He wasn’t into this. And then in those days everyone was doing sidelines. Key cutting, watch batteries, watch straps. So everything’s diversifying.’ Nick goes on to situate the introduction of key cutting in 1991 against the backdrop of changing provisions to retailing in the area: ‘I think because obviously it was busy times. And people need keys. So where they going to go? Hardware stores were sort of disappearing from the High Street. So yeah, we got into this.’

Today, Nick’s shop is a small, narrow property with just enough space for his shoe repair machinery, tools and equipment behind the counter and perhaps one or two customers inside the shop at any given time. Next door, is a similarly small independent coffee shop with young baristas and downtempo electro-pop music playing inside. Nick was forced to divide the shop containing his shoe repair business into a small unit, while relying on the rental income from a new business more resilient to modernity’s taste. Though Henri Lefebvre’s incisive critique of contemporary capitalism having ‘colonised’ everyday life was not, categorically, discussing the proliferation of bougie coffee shops across London, it rang true for a moment. On my way out, I wavered, feeling awkward but inevitably spent £3 on a coffee at the insignia of gentrification next door.

*

The changes to the city are not just felt in the built environment of our neighbourhood but reverberate through to the interpersonal relationships and reflections from my interlocutors. Born in Tanzania to a cobbler father, Adil remarked with pride that his dry cleaning shop had stood on the high road for thirty-eight years, still run by him and his wife Mina today. ‘In those days everyone knew me. People knew me. Nowadays…’ his voice trails off and he stops speaking, focused on smoothing the black dress shoe in his hand. Adil often speaks in fragments punctuated by his moving through tasks. After a moment he says, ‘Back in the day, the Irish people were good customers. Big spenders.’ He stops suddenly to look at me, the first time he fully takes me in since I’d been at the shop and asks me where I am from. I share that I am also of East African heritage and he seems to acquiesce, nodding his head slightly. ‘Africans know hard work. And the Irish!’

It is perhaps ironic that both of my cobblers, Adil and Nick, shared the most nostalgic and affective recollections of their working lives. At once being associated with a centuries-old trade that has sought ways to evolve through macro-level changes in industrialisation, the casualisation of dress and the capriciousness of a fashion system that has relegated repair to the dark recesses of our own wardrobes and perhaps imaginations.

Yet curiously, I watched as contemporary fashion objects triggered alternative strategies for both Nick and Adil. At Nick’s, I spotted a Maison Margiela boot in the Japanese ‘tabi’ style. Nick was intrigued as I told him about their current popularity, and he gushed at how this unusual style of shoe would offer a challenge to his standard practice of resoling. He said, ‘See, it’s things like that I have to adapt to.’ On demonstrating how tricky it would be to trim between the shoes’ toe-split, he says, ‘It’s gonna be a challenge. That’s one of the challenges of probably the year.’ At Adil’s, a woman brought in a pair of trainers belonging to her son that were familiar to me as a replica of the style of Adidas ‘Yeezy’ trainers with a retro protruding silhouette and an apparent hole. After a minute of inspection and questions like ‘What caused the hole?’ and ‘Did you put glue in it?’ Adil advises against a repair, telling her she’s better off buying a new pair. When she leaves, he returns to tinkering around his workstation and mutters in a sing-song voice, ‘Everybody wants trainers.’

At another time, Adil tells me, ‘Nobody wants to do this job’ in response to a loaded question about whether he enjoys his line of work. He turns the question around to me, asking me directly ‘Would you do this job?’ I reply with something about wishing I had the skills to ‘do things’ and that drove my interest in understanding more about his work. ‘Everybody wants to be an officer.’ Adil repeats this twice for emphasis, again in his sing-song-like cadence. ‘That’s all I can say.’ What Adil was saying is that everyone wants an office-based job. His comment made me think about the contemporary office as a moralising space but instead of tangible outputs, the day-to-day is often made of superfluous tasks. I scribbled ‘bullshit’ in my notes and thought about David Graeber’s argument that the majority of contemporary work serves no utility, and about my own ‘bullshit job’ that had inadvertently pushed me to make sense of repair.

*

Parvez is the owner and manager of Beam’s dry cleaner. Despite not having a ‘hands-on’ job in the business, he reveals the tactile experience of doing, or manual work, as having been his best option in the job market since immigrating to the UK twenty years ago, recalling jobs in a supermarket, as a cab driver, and as a mechanic. If garments and the repair and maintenance towards them are ostensibly feminised in scholarship and public imagination, when applied to work, and in the context of running a contemporary business, it emerges as a masculine meta-narrative for Parvez. ‘If you work for your family you’re the man. That’s why proud always I work. I don’t mind anything, even grasscutter, cleaning the roads. As long as you make money. And your children happily spend it. They proud, even they proud. That’s a man should think that like. If you shy like, oh, it’s not a good business. The name, it’s cleaning or its grass cutting or it is carpenter or it is builder. No. I love even I see someone coming to the bus or to the train with a work clothes. I love them. I feel proud of them.’ He situated his work at the dry cleaners as one of both necessity, his obligation to his family, and in pride, in being a productive member of society, regardless of how maligned a trade, occupation or profession may be. Making money is the objective and in many ways the social equaliser.

Parvez tells me that there is a ‘Beam’s Dry Cleaner’ in America, Australia and Canada. The naming of the shop was unintentional but now has the added means of forging a transnational connection to these businesses. He says with pride that a tourist once recognised this and shared, ‘Oh I use you guys in New York.’ There is a small boutique hotel across from the dry cleaners, though it’s on the local high road it markets itself as being in a more fashionable, and affluent, London area. Parvez says it’s good for business if guests at the hotel associate them as being part of a franchise; he says ‘It sounds big you know.’

*

Repair forces us to confront failure because it’s a reminder of the infallibility of things. I gravitated towards studying repair as a lens into thinking about fixing; garments, objects and the erasure of everyday workers in scholarship. I found that repair opens up a wide range of questions about responsibility, care-taking and potentiality. By taking seriously the ‘mundane’ and routine of everyday life, repair practises can enrich our conception of fashion work in the overlooked and undervalued sphere of contemporary service work, revealing the contributions of those at the margins of a formal fashion industry yet intimately associated with the tactility, and (re)making of garments. In any case, fashion should have a duty of care towards ‘repair’. As a growing commercialised service offered by multinational fashion brands and retailers, the future for our everyday high-street garment repair shops like Adil, Nick, Parvez and Moshda’s is in question.

Diamond Abdulrahim is a London-based brand strategist, fashion researcher and writer.