While browsing the resale app Depop, I frown, one eyebrow slightly cocked. I stare at my phone screen trying to distinguish what looks like an architectural slice of fabric strewn on the seller’s bedroom floor. On closer inspection, it is a brown long sleeve top with a network of drawcords covering the torso, corset ties running the gamut of the sleeves and a large keyhole cutout on the back. The caption reads ‘Insaneee cut out top, super sexy loads of ways to wear. Such a unique piece!’ Among others, one tag mentions subversive basics.

A term coined by the trend analyst Agustina Panzoni on her TikTok channel, @thealgorhythm, subversive basics refer to garments that ‘rebel up to the point of losing their utility.’1 By this Panzoni identifies a subset of everyday garments in both mens and womenswear categories that have been reworked with cutouts, slashes, layering, mesh panelling, ruching and piping. The stylistic applications of subversive basics with its lingerie influences and deconstructivist sensibilities pertinent to the 1990s, define the trend by its accentuation and exposure of the body as well as the garment’s ability to adapt and alter to the whims of the wearer. They are an exploitation of immodesty. T-shirts are made unabashedly revealing with the pull of a drawcord, vests are sliced and spliced together barely clinging to the shoulders. Knits no longer indicate warmth or necessity, they are reconfigured and now are merely an accessory. The little black dress is now even smaller with sections of fabric gouged out of it. At any moment, an ill-judged movement threatens to flash a body part that would rather remain hidden.

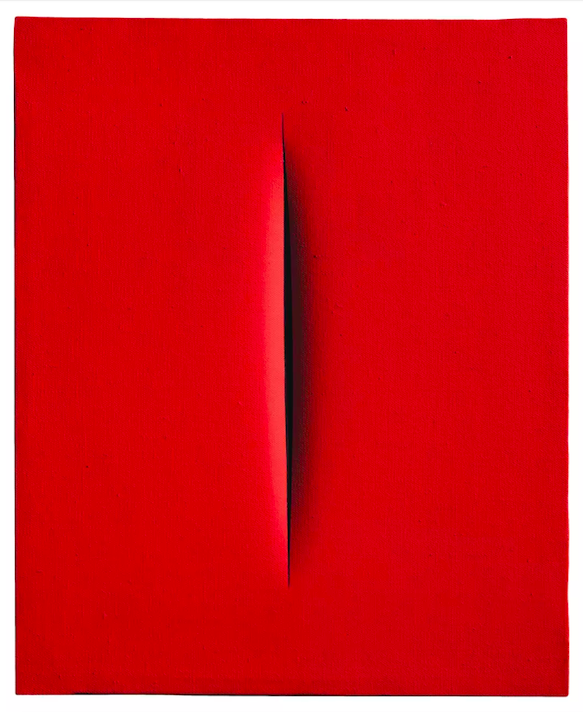

With an abundance of skin on show, subversive basics are symptomatic of the psychologist J.C. Flugel’s theory on the ‘shifting erogenous zone.’ It suggests the eroticism of the body is sustained by clothing that continually shifts the emphasis from one specific area of the body to another that conjure sexual stimulus or desire.2 Erogenous zones are accentuated through exposure, semi-concealment and other devices at a designer’s disposal. Subversive basics utilises it all, but undermines the body’s proclivity for eroticism. The erogenous zone is fractured into insignificant swatches of skin that vie for attention. To completely reveal the body would be anti-erotic and antithetical to the point of fashion – the display must be extreme enough to be exciting, but not too extreme so that it is obscene. Potency lies instead in our imaginations that extrapolates the suggestion of the nude. The power and allure of the erogenous zone is in its singularity – framed and isolated, a strategic revelation that catches the eye, commands attention, flirts, provokes and coaxes with each movement. When fractured and split into multiple zones, the eye is distracted and the efficacy is diffused. These garments, in all their festooning, signal that the body has exhausted its erotic capital and reached an impasse where, all at once, everything and nothing is erotic.

Previously, notions of taste and respectability were more pervasive with fewer designers defining the fashions of the period and therefore being able to delineate a singular erogenous zone. The 18th century saw significant areas of skin emerge coinciding with the dawn of modern social and sexual relations. By the Empire period, busts were suspended above the bodice, nipples exposed through veiling and fichus. At the close of the 1920s, a woman’s legs were no longer deemed erotic as men grew tired of their overexposure, hemlines were dropped to conceal the legs, attention was shifted to the back, which was bared to the waist, the skirt drawn tightly over the hips to accentuate the buttocks. Comparatively, men’s fashion oscillated with equal flamboyance to enhance various parts of their physique – great voluminous sleeves, padded doublets and codpieces in the Tudor age, and the ‘poulaine,’ a long shoe in the shape of the phallus popular in the Middle Ages, all served to exaggerate a man’s stature.3 Only from 1760 onwards was an anti-fashion uniform adopted and male erogenous zoning became more stable, the contrast owed in part to the continued social and sexual scrutiny of women.

Erogenous zones become sterile with overexposure and erotic capital is maintained through this gradual shift from one area to another, engaging in a game of hide-and-seek between seduction and prudery. What prudery resists and eventually accepts after a particular emphasis has been established has left little to be considered shocking. After all, every part of the body has been paraded and shamed at some point. As the fashion system has modernised and proliferated, more designers and brands compete for attention and a point of view. The speed at which the erogenous zone shifts and oscillates has accelerated and outpaced us, darting across the body, never truly landing.

The multiplicity of these garments with their excess of straps, cut-outs and slits reduce the erogenous zone to a non-place. The French anthropologist Marc Augé refers to these non-places as transitory spaces, in spacial design they might include places such as airports, hospitals, motorways, where we experience a feeling of gentle possession. Our movements and gestures are controlled and guided as we pass through them as anonymous individuals, not relating or identifying with these locales in any intimate sense.4 The customisability of these garments render the erogenous zone transient and temporary meaning that we do not relate to it in an intimate, sensual or erotic capacity. In both instances of non-place, individual and erogenous zones experience a sense of identity loss. The individual becomes submissive to the space, while the erogenous zone becomes just an area of bared flesh competing with other points of exposure. Stained by time, subversive basics create an experience of similitude where they reference multiple garments and erogenous zones, without definitively embodying one. Desolate place, desolate garment, the poetics of being cease to thrive here.

The trends proliferation is synonymous with the lifestyles of our current society – one that has become increasingly obsessed with image, excess and novelty. One moment, you are hoisting your top up, yanking at the pulley system of ties to reveal your midriff, and before the marks from the straps pulled too tight have left the skin, you have released the pressure, moved your attention to your trousers, accentuating the cutouts on your thigh, not yet sunkissed, to be paraded to the world. What was once the risqué baring of flesh that tiptoed between the terrain of shame and shamelessness, has now been replaced by an exercise in exposure in both the physical and digital sense. Designs are now created to please the algorithm and market to the influencers who command it. Brands and fashion houses are no longer sartorial authors in the traditional sense, but rather amalgamators of data.5

The ubiquity of subversive basics across the collections of designers as varied as Rick Owens and Mugler to Jil Sander and Telfar suggests that what the data demands are garments that reflect the destabilised environment around us. It is well understood that the body represents a physical and social entity under construction and one of clothing’s functions is to assuage our fears and vulnerabilities over our corporeality. Subversive basics acutely reflects the current anthropocene of the individual being a ‘work in progress’ or ‘in transition’ towards an avatar of their own creation.6 It makes complete sense that the ties and pulleys of this trend conjure to mind a construction site, while the cuts, tears and slices are reminiscent of the surgeon’s table. As a catalyst to this condition, online media is geared towards simulation, stimulation and desire. Faceless e-commerce imagery, outfit shots, nudes, digital filters and editing have all worked to establish a visual lexicon of bodies presented in vignettes and fragments. Consumption of these fragments reflect desires that are built on a disconnected and disembodied relationship with ourselves. Faceless and limp, interacting with these phantasmatic torsos has contributed to a disjointed perception where stimulation and excitement is derived from dismemberment rather than totality.

In Augé’s later writing, he outlines that ideas of the future have taken on a new dimension that displays several faces that encapsulate our desires, hopes and fears.7 Insatiable, complicated and conflicting, the accentuation of this bipolar character is physicalised in subversive basics. Garments become palimpsests, where identity and our relationship to it are being ceaselessly rewritten, mutating from one design to another in an attempt to satiate us for a fleeting moment. The reciprocal interdependence that clothing and the body has with one another will always furnish new conflicts. Subversive basics are not a reconciliation of these frictions, but represent an ongoing project where we are slicing everyone up to create a new set of ideals. There is little left to bare, the traditional erogenous zone exists and continues to shift, but its potency has been undermined. The new ideal being prepositioned is that the body is slippery at the margins, but now the clothes are too.

Felix Choong is a curator and editor of Nice Outfit, an exhibition catalogue and theoretical journal, who lives and works in London.

https://www.tiktok.com/@thealgorythm/video/6951466402205224198?is_copy_url=1&is_from_webapp=v1&lang=en ↩

J.C. Flugel, Psychology of Clothes, Hogarth Press, 1940. ↩

Valerie Steele, Fashion & Eroticism, Oxford University Press, p. 35, 1985. ↩

Marc Augé, Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, Verso, 1995. ↩

Taylore Scarabelli, Styling for Social Media, Viscose Journal, p. 71, 2021. ↩

Natasha Stagg, Sleeveless, Semiotext(e), p. 233, 2019. ↩

Marc Augé, The Future, Verso, p. 7, 2015. ↩