Iran is currently in the news because of the sanctions imposed by the Trump administration and the threat of an imminent war; mostly the reports are centred around descriptions of oppression by the hard-core Islamic regime that has been in charge since the 1979 Revolution. Since the deposition of the Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, Islamic clerics have ruled the country imposing shari’a law, and decreeing that women should cover up to protect their modesty. ‘Iran’ and ‘fashion’ are, in the popular imagination, an incongruity. Reality however is, as always, more multifaceted. The cultural anthropologist Alexandru Balasescu has written about Iranian fashion in Tehran and in Paris.1 He was among the first to point out that despite dress regulations – the obligatory hijab or headscarf, the manto or coat, and the black cloak chador – fashion in Iran (in the sense of dressing stylishly and making a personal statement), particularly in urban centres, is definitely not absent. His remarks have been reiterated by Elizabeth Bucar, a religious ethicist who has studied ‘modest wear,’ which she prefers to denote as ‘pious fashion.’2

Iranian fashion is not encased in the structure of public catwalk shows and magazine editorials. Fashion magazines with images of women are not available, nor is modelling open to women as a profession. Men, on the other hand, do model, as shown by ubiquitous city billboards, conveying the aspirational image of a businessman or professional, bearded and impeccably suited and booted. Fashion as an industry does not receive recognition at governmental level: officially it does not exist, despite the myriad of shops, boutiques and home-based ateliers found in most urban centres.

Women in Iran, much like women everywhere, want to wear stylish clothes in an individual manner. The interviews with and portraits of contemporary Iranian women published on blogs like the Paris-based The Teheran Times, run by Araz Fazaeli, are a far cry from the stereotype of a chador clad militant and through them we can get a sense of the lively debate around female dress and agency currently taking place in Iran.3

Through social media women create, and are aware of, fashion trends, with many women using them to post and comment on daily life and lifestyle. Fazaeli’s The Tehran Times has now become a reference point for those who want to know about lifestyle in contemporary Iran, as well as art and culture, thanks to the media exposure the blog has received outside Iran and its strong social media presence. Iran has a very lively art scene, and, according to Fazaeli, a very intense nightlife based on private parties and gatherings.4 Alcohol circulates freely at such parties, even though alcohol consumption is regarded as a severely punishable crime.

The Morality Police, known as Gasht-e Ershad, instituted to check up on the appropriateness of women’s everyday attire and compliance with the rules, is active, though nowadays it is often unable to intervene because of the sheer number of women resisting publicly by openly defying the dress regulations.5 Iranian women continue to change the rules of the game in matters of dress, despite the authorities occasionally deciding to make an example of the more prominent rebels, as in the case of human rights lawyer and women’s rights defender Nasrin Sotoudeh, condemned to thirty-three years in prison and 148 lashes in March this year. Sotoudeh had been acting as defence counsel to women arrested for protesting against the hijab laws.6

* * *

Earlier this year, I had the opportunity to travel to Iran. As soon as I landed at Tehran international airport I was met by my guide, whom I had hired for the day. Sarah (not her real name) is in her late thirties. At our first meeting, she wore an elegant green cotton manto, open at the front (an optional brooch could be used to hold it together, but Sarah did not bother). Her hijab was a Valentino scarf, which she had bought in Paris as she often takes Iranian groups to France and Spain. She wore her hijab draped over her abundant highlighted brown hair, allowing a few curls to escape. Under her manto, she wore a brightly coloured, spaghetti-strapped top that finished at her waist and matched her hijab; her bottom half was clad in black lycra leggings and on her feet she wore a pair of trainers.

Sarah’s make-up was flawless though somewhat heavy by European standards, and her hands were well-manicured by any standards. At the end of my first day in Tehran, after visiting the National Jewellery Museum, we went together to a well-known salon for a manicure and, for me, a much needed pedicure. Here, in a women-only environment, hijabs and mantos were left in the hall. I saw women in tight shorts and skimpy camisoles, their hair coloured in many different hues and imaginatively styled. Some women smoked on the balcony. It was something I had read about but did not expect to be able to witness.

The following three weeks were full of surprises. I flew to Shiraz and joined a small group of Australian tourists whose tour Sarah was leading. Every time we went to a site, we met Iranian tourists as it was the holiday season, just before Ramadan. Shiraz is also a centre for cosmetic surgery and I saw many women, from all walks of life, including a couple of chambermaids at the hotel where I was staying, with large plasters on their noses – Sarah told me they had just had a nose job. Apparently, it’s a craze now in Iran: nose and lips are what women are the most keen to modify.

I saw women of all ages posing, like models, for photos meant to be posted on Instagram, which is allowed in Iran, unlike Facebook, though the use of a VPN allows most people to bypass restrictions on online access. Some even dared remove their hijab for a picture or open up their manto to show their cleavage, posing provocatively, yet jokingly. Some women were engaged in full blown photo shoots, with professional-looking cameras, which no doubt were meant for blogs; the historic sites provided a wonderful backdrop. The blogging phenomenon, despite official interventions to regulate it, and the occasional clampdown, has seen the rise of what communication scholars Annabelle Sreberny and Gholam Khiabany have named ‘Blogistan:’ ‘a space of contention between the people and the state.’7

I became aware of the tricks many women played with their hijab, dropping it to show off their well styled hair and then swiftly repositioning it, halfway on top of their head, sometimes pinning it, sometimes not bothering, unless the Gasht-e Ershad were about – there is now an android app that warns of their presence. Under their often unbuttoned manto there were tight tops and tight leggings or ripped jeans; some mantos were made of see-through material. It was clear that women, especially young women, were finding ways of getting around the dress restrictions and seemed to be able to do so successfully. Sandals, often with heels, seemed to be very important to the way they styled their everyday attire: wherever I went I saw perfectly pedicured feet.

In Esfahan, over a cup of Turkish coffee, Sarah told me that Iranian women had come a (comparatively) long way, being able to wear bright colours and choosing to personalise their attire, even showing off their often long hair by wearing narrow hijabs which could not cover the entirety of their hair. ‘When I was at university, in the early 2000, we had to fight to wear blue; only black was allowed; look at what we can wear now,’ she said, pointing to a woman in different hues of red.

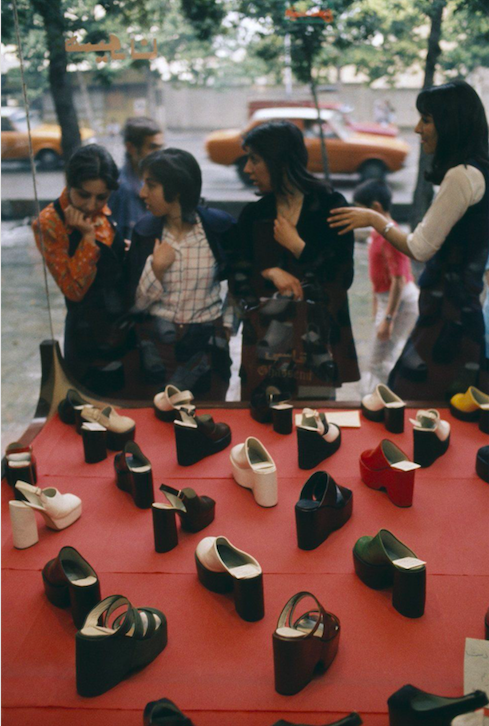

Also in Esfahan, a young woman who worked at a bookstore in a five-star hotel told me, after admiring the hijab I had just picked up from the shop next door, ‘it’s nice, but it’s only temporary for you.’ She wore a magneh, a piece of fabric that covers both head and neck and is fixed in such a way that it cannot slip off like a hijab. ‘My boss would allow me to wear a hijab like yours, but I have to bend down, lift boxes, the hijab would come off and then security would complain,’ she added with a shrug. She then showed me a magazine that was on display on a shelf behind her. It was a fashion magazine that had been printed in pre-Revolution days and for some reason it was on sale among the books. ‘Look here,’ she said, pointing to a page with two different photos, one of an Iranian woman on a beach wearing an orange bikini, with a very 1970s feel and look, and another of a chador clad woman in an Iranian village.8 ‘Choice. We do not have that. Yet. That’s all I am asking for.’

* * *

In contemporary Iran the way women dress has become a political statement. Officially, there is no choice in the matter of female clothing, but during my trip I witnessed women expressing their personal preferences continuously. Theirs is a fashion sustained by everyday choices, and negotiated on an everyday basis. By subtly reinterpreting the rules and sensitively opposing the Morality Police, the women here are aware that accommodating changes takes time: baby steps leading to more changes.9 Iranian women carefully choose what and how to wear specific items of clothing in their quotidian life. Not all Iranian women dress with the conscious aim to defy the regime, of course, but almost all of them try to make their choice of clothes as individual as possible, paying great attention to styling and making use of social media to present and discuss their style with friends.

My visit to Iran has made me reflect on the whole issue of ‘modest wear’ and in particular, coercive wearing of the hijab. I did not get the impression, in Iran, that the hijab and manto were merely the expression of a Muslim identity, freely embraced. A lot more was at stake; the issue is political rather than religious. Here I am mindful of Islamic Studies scholar Faegheh Shirazi pointing out, in 2003, how the hijab acquires different meanings in different contexts.10 The very fact that I, a non-Muslim, had to wear hijab and manto everywhere (except in my hotel room) ‘because this is the law’ as well as the sustained attempt, on behalf of many Iranian women, at removing their hijab or at the very least, personalise their attire in whatever way they could, reminded me of coercive school uniforms or even prison uniforms. As has been previously noted in this publication by Anja Aronowsky Cronberg: ‘prison life is full of upturned collars and resentful squints, as well as a myriad of other ways to subvert the rules, however slightly.’11 The streets of Teheran are full of proverbial upturned collars too.

Masih Alinejad, who began the #WhiteWednesdays campaign12 and who currently lives in New York, unable to return to Iran for fear of reprisal, has stated, in a widely commented debate on CNN with pro-hijab American-Palestinian activist Linda Sarsour: ‘I don’t see any Muslim communities in the West being loud and condemning compulsory hijab, especially you, when people of Iran are putting themselves in danger and risking their lives… I never saw the feminists in the West condemning compulsory hijab when they go to my country… They go to Iran and they obey it … All I see is double standards and hypocrisy.’13

Touché.

The hijab issue is mired in controversy; it is a political act to wear it, just as it a political act not to wear it. Opinions will remain divided for a long time to come. One thing, though, is certain: the desire for expressing individuality cannot be stifled, despite the seemingly frantic attempts by the Iranian government to wage a war on ‘bad-hijab.’

Alex Bruni is a model and a writer. Her book Contemporary Indonesian Fashion: Through the Looking Glass is published by Bloomsbury.

Alexandru Balasescu Paris Chic, Tehran Thrills: Aesthetic Bodies, Political Subjects, Bucharest: Zeta Books, 2007 ↩

Bucar writes that ‘the word pious is more appropriate than modest because it captures a number of ethical and religious dimensions of this clothing… creating a public space organised around Islamic moral principles.’ Elizabeth Bucar Pious fashion. How Muslim Women Dress. Cambridge, Massachussets/London: Harvard Unioversity Press, 2017, p.3 ↩

The Tehran Times available at http://thetehrantimes.com/ ↩

Araz Fazaeli, ‘An urbanist guide to Tehran’ The Guardian 10/3/2014 available at https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/mar/10/blogger-week-araz-fazaeli-tehran-iran ↩

Iran has had various forms of Morality Police to check on ‘bad-hijab’ and other transgressive behaviour. The current Gasht-e Ershad is an offshoot of Basij, a paramilitary unit and it comprises both men and women, sworn to the revolutionary cause. It has been reported that in June 2019 the Iranian government announced they would hire 2000 more female police in the Caspian region to crack down on hijab transgressions as well as introducing a system of reporting neighbours for ‘moral crimes’ by text message. See Borzou Daragahi ‘Iran invites people to turn in neighbours for “moral crimes” by text message’ The Independent 11 June 2019 available at https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/iran-text-message-moral-police-code-violation-tehran-crimes-a8952361.html ↩

Amnesty International News available at https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2019/03/iran-shocking-33-year-prison-term-and-148-lashes-for-womens-rights-defender-nasrin-sotoudeh/ ↩

Annabelle Sreberny and Gholam Khiabany Blogistan.The internet and politics in Iran, London: I.B. Tauris, 2010, p.viii ↩

The chador is now only used as part of formal dress by women in public service and has to be worn when entering a mosque, but it was obligatory soon after the Revolution. Iranian women, unlike the Saudi, do not cover their faces. Iranians are shia Muslims, not sunni, and there are some differences in their respective interpretation of Islam and its rules. ↩

A short film on YouTube visually sums up fashion and beauty developments in Iran over the last one hundred years. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G7XmJUtcsak&t=2s ↩

Faegheh Shirazi The veil unveiled: the hijab in modern culture, Gainsville: University Press of Florida, 2003 ↩

Anja Aronowsky Conberg, ‘Docile Bodies,’ in Vestoj On Shame, 2011. Also available at https://vestoj.com/docile-bodies/ ↩

Iranian women posting pictures of themselves wearing white hijabs or white clothing to protest against the imposition of a mandatory hijab; the protest began in 2017. Alinejad is also the author of The wind in my hair. My fight for freedom in modern Iran London: Virago, 2018 ↩

Katy Scott, ‘Macy’s decision to sell hijabs sparks debate among Muslim women,’ CNN 20 February 2018 available at https://edition.cnn.com/2018/02/17/middleeast/macys-hijab-debate/index.html ↩