ON A RECENT SATURDAY morning, I dream about clothes. On a single rack in a sparse space hang voluminous skirts in heavy, vintage fabrics of vermillion, baby pink, cherry red and monochrome; a jumpsuit in pastel stripes with rows of fringe; an off-the-shoulder dress of the softest silk in a rich, plum hue; and a collared shirt patterned with puzzle pieces. I run my hands over each piece, lovingly, longingly, prepared to buy and wear each one. They are completely within my grasp… Then, just as suddenly as I’d drifted off that evening, the dream ends, leaving me with little more than fragmented images of beautiful garments in a white-walled room. A question lingers, too: What – if anything – might the presence of these clothes in my dreaming mind mean? And why bother paying attention to them at all?

As I learn the following Sunday afternoon, this particular dream actually served as a confirmation of sorts – a sign that my unconscious and conscious minds were in sync. I bring my dream to Sarah Berry-Tschinkel, a New York City-based Jungian psychoanalyst in private practice who earned her M.S.W at Smith College and has worked in the field for over two decades As she explains in her sun-dappled office in downtown Manhattan, clothing and self-presentation have long held a particular fascination where the unconscious is concerned, even when that opinion has proven unpopular and unexplored among her colleagues. An actress by trade (analysing dreams marks her second career), Berry-Tschinkel pays close attention to what she terms the ‘embodied experience’ when she works with her clients. ‘Self-care and really understanding how you feel in your own skin – how you walk around in your own body – that to me is both fascinating and an important part of being a human being,’ she says.

Coming prepared is key to ensuring a productive and insightful session with Berry-Tschinkel. Before a new client arrives to her office, she asks them to choose a dream of late that they recall in relatively great detail (‘It’s the psyche saying, ‘Here I am.’’). She starts with the personal, asking such questions as, ‘What did the hat look like? Did you ever have a hat like that? Did it hold any significance for you? Did your grandmother have a hat like that?’ Then she tackles the symbolic and cultural associations, which naturally differ from client to client. Suffice to say, once you begin breaking down a single dream piece-by-piece – and garment-by-garment, as applicable to my session – you could quickly find yourself in a complex maze of possible interpretations. Berry-Tschinkel works to guide her clients through that maze and toward a sense of greater clarity about what their dreams might be trying to tell them.

When I ask what originally attracted Berry-Tschinkel to study Jung’s approach over Freud’s, she points to the Jungian belief that dreams hold ‘the potential of being prophetic or expansive or deeply creative…’ The distinction between Freudian and Jungian approaches to dream analysis is subtle yet significant. In contrast to a strictly Freudian approach – wherein dreams signify repressed contents and desires that may only be safely accessed via the unconscious, so as not to disturb our waking lives – Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung believed that our individual consciousness existed in intimate relationship to, and arose out of, our unconscious mental state on a daily basis. He theorised that understanding our dreams provided a means for the unconscious to communicate with the conscious mind in our waking lives. As he wrote,

Consciousness does not create itself – it wells up from unknown depths. In childhood it awakens gradually, and all through life it wakes each morning out of the depths of sleep from an unconscious condition. It is like a child that is born daily out of the primordial womb of the unconscious. …It is not only influenced by the unconscious but continually emerges out of it in the form of numberless spontaneous ideas and sudden flashes of thought.1

Applying the more open-minded, Jungian line of thinking to the visual and sensory contents of dreams ultimately allows for more generous – and generative – interpretations. It’s exactly why I sought out a Jungian analyst to help me unlock the underlying message that my recent dream featuring vibrant clothes at its centre might have been trying to send me.

Berry-Tschinkel was trained to think of the dream life ‘as much bigger territory.’ In short, every detail counts when you’re thinking like a Jungian. In clothing-centric dreams, sensory details ranging from colour, texture or quantity of garments to the feel of fabric on skin to childhood memories associated with the garments often enrich a preliminary interpretation. On occasion, Berry-Tschinkel might even encourage her clients (as she did me) to draw what they saw. This helps them to imagine what it might feel like to wear the clothes in the real world, beyond the dream landscape. Sometimes, the potent mood or feeling that wearing the clothes conjures matters more than the literal presence of the clothes themselves.

I experienced an ‘ego-near’ dream, according to Berry-Tschinkel. This means that the imagery that arose was not too far outside of my usual taste and sense of self, as demonstrated by the fact that I was the only figure present, save for the clothes, which provided me with a potent sense of pleasure and excitement. Berry-Tschinkel’s guess? ‘This in some ways was telling you you’re on the right track. There’s something here that fits you. That it is yours to have. And it’s waiting for you.’ She specifically calls this a ‘confirmation dream,’ in that the clothes, and the emotional significance they held for my psyche – a sense of possibility and joy – were accessible and within reach, even if they were not yet tangibly mine.

When talking about clothing in dreams, persona – a term coined by Jung to mean the personality that one projects to others, in contrast to what they consider to be their ‘authentic self’ – repeatedly arises. Persona constitutes one of Jung’s four central archetypes (the other three being the self, the shadow and the anima or animus).2 It’s fitting that he derived the term from the Latin persona, referring to the masks worn by Etruscan mimes.3 (But think of it less as a literal mask than as a social mask.) According to Jung, the persona may also appear in dreams – and that’s where clothing comes in. Just as people utilise clothing as a vehicle for self-expression in their waking lives, clothes often play a similarly expressive role in relation to the personas we assume in our dreams.

At a time where constant image control and maintenance, particularly across social media, is at its cultural height, the persona’s role in dreams has only grown more idiosyncratic. As Berry-Tschinkel explains, ‘it used to be that one had a persona that was both conscious and unconscious, but it stayed pretty consistent. If you were a doctor or a teacher or a minister, you had a role, and your persona was often consistent with your role. Your dress, your manner, the way you conducted yourself, the quality of your voice, was consistent with that. But we have a much more – interesting and creative, I think – relationship with persona now.’ When she sees persona in dreams, she often thinks of it as ‘a new aspect of persona being tried on.’ Just as a new outfit sometimes allows us to tap into previously unexplored parts of ourselves, trying on clothing in a dream as a tangible expression of persona might signify ‘an opening up of new aspects of identity as yet unknown.’

I wondered whether my dreaming of clothes in such vibrant detail was a rarity. Turns out it’s not, even if some analysts prioritise its meaning more than others. Berry-Tschinkel estimates that at least half of the dreams of people she works with involve clothing in some capacity, whether it’s a garment left behind or something they take on or off. For instance, someone who is not prone to dressing loudly in her day-to-day life might don ‘oranges and turquoises and reds’ in a dream, suggesting that ‘something more colourful needs to be expressed or that they have the possibility of opening up a more dynamic part of who they are, and they’re not there yet.’

Other times, though, the absence of clothing proves equally significant. Nudity constitutes one of the most constantly recurring dream images. According to Berry-Tschinkel, this can signify that ‘something is being revealed too quickly,’ or that someone is ‘not quite comfortable yet with what is being revealed or…how it’s being revealed. There can be a thousand different ways that you interpret that depending on what someone’s issues are and where they are in particular their life.’

For as much as Berry-Tschinkel pays attention both to what clients recall wearing in dreams – and even what they wear to an appointment with her – as a meaningful access point into their psyche, she laments that, in her field, creative expression has not often been written or talked about. This may, in part, come down to the fact that not all clients come bearing ‘creatively expressive’ dream imagery for an analyst to work with in the first place; more creative aspects of their psyche might be blocked or relatively inaccessible, due to the way they were raised or based on the relatively insignificant role they consider clothing to possess in their daily adult lives.

Yet there might also be some gender issues at play. Consider the central role that fairy tales and mythology play in the Jungian psychoanalytic field. Marie-Louise von Franz (1915–1998), the foremost student of Jung, with whom she worked closely from 1934 until his death in 1961, published widely on the intersection of dreams and fairy tales,4 often examining their central motifs in relation to Jung’s concepts of shadow, animus and anima. In studying fairy tales through a Jungian lens, von Franz believed they would offer insights into humankind’s shared archetypal experiences. Yet within these archetypically rich tales, Jungians have long privileged what Berry-Tschinkel refers to as the ‘hero’s quest,’ or ‘mythic journey,’ wherein the presence of seemingly insignificant details (e.g. what the protagonist wears whilst overcoming dangerous obstacles) are often relegated to the background. This is further complicated by the fact that many of these same fairy tales and myths are more prone to highlighting women’s appearance and clothing as notable elements (as in Cinderella or Rumpelstiltskin) while not placing equal importance on such elements for male characters.

Early in her career, Berry-Tschinkel observed a notable chasm between the content of such psychoanalytically relevant tales and the content of dreams as her clients presented them to her. ‘I would go back and look at what dreams were analysed and what the books were written about, and they were all about slaying the dragons,‘ she explains. ‘And I was looking at the dreams of my patients, and many of them were like, “Well, I had this blue sweater on and it had these tiny little buttons and they were pearls.” And I think other of my colleagues might miss that. They might not explore what that feels like. You know, what blue is in the client’s life and what it felt like [for them] to button up those tiny little buttons. I found that it took us into really interesting territory that was deeply about an embodied sense of the self, and it was incredibly rich.’

As someone with a demonstrated passion for personal style, I ask Berry-Tschinkel how much of herself she brings into the room when meeting with a client who comes bearing a sartorially rich dream. Does she ever get carried away? ‘What I try to do in my work with anyone is to stick very closely to what they bring me, because it needs to about their experience – not mine. And I can certainly bring insights to that, but I try to skew very closely to their imagery, their interests and what they bring into the room. Because in that way, I’m listening to their psyche.’

After I left Berry-Tschinkel’s office, I thought about how I’d never felt quite as immediately understood by a stranger I had met but an hour ago. In taking my dream clothes seriously – in thoughtfully and imaginatively considering how they connected to the person that was, at that moment, striding down Fifth Avenue toward whatever the future held, in platform boots and a printed dress salvaged from the fifties and a black faux fur coat – Berry-Tschinkel had not only listened to my innermost psyche: she had seen it.

Olivia Aylmer is a New York-based writer, editor and graduate of Barnard College at Columbia University.

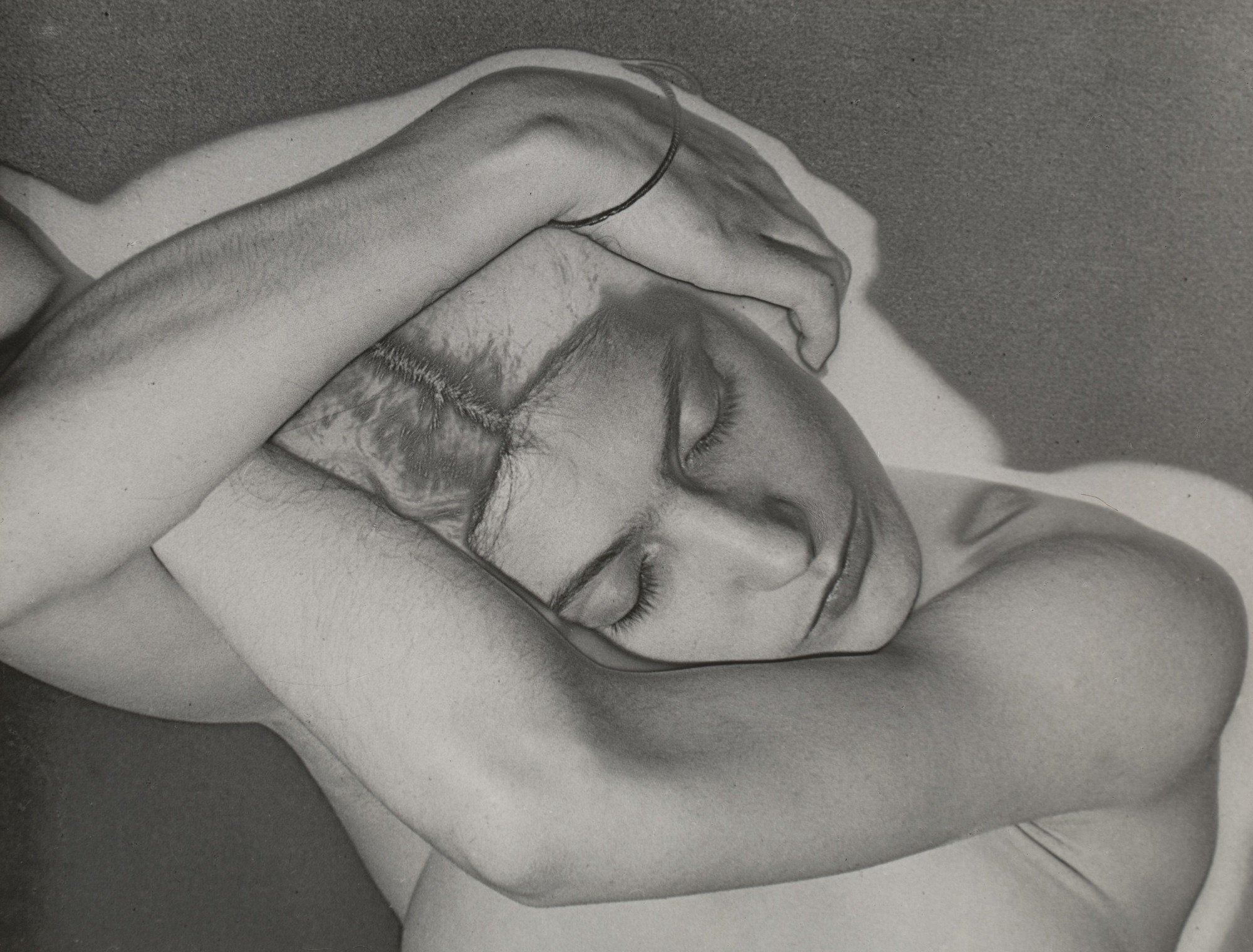

Photograph courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art (www.moma.org).

‘The Psychology of Eastern Meditation,’ par. 935, in CG Jung, The Collected Works of C.G. Jung. Ed. Herbert Read and Gerhard Adler. Trans. R. F.C. Hull. 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton UP; 1975. ↩

According to Jung, the self is the sum total of the psyche, with all its potential included. Those traits that we dislike form what Jung called the Shadow, a part of the psyche that is also influenced heavily by the collective unconscious. The anima and animus are the contra-sexual archetypes of the psyche, with the anima being in a man and animus in a woman, which seek to balance out one’s otherwise potentially one-sided experience of gender. See: Journal Psyche, “The Jungian Model of the Psyche,” http://journalpsyche.org/ ↩

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. ‘Persona.’ Encyclopædia Britannica, 12 May 2005. ↩

For further reading, see von Franz’s The Interpretation of Fairy Tales. Shambhala, 1996. ↩