What we learned in school about labour and capital: it begins with the project of modernity, a history of domination and colonisation, which lead to the rise of the industrial revolution in the eighteenth century. From craft to looms and machines of mechanisation, our history books teach us that the nineteenth century was marked by the birth, rise, and making of standardised, industrial products. Capital derived from ‘the economy of machines and manufacturers,’ what the philosopher and inventor Charles Babbage marveled as ‘the accumulation of and science which has been directed to diminish the difficulty of producing manufactured goods.’1 He was fascinated by the Jacquard-loom, which could reduce the number of hand weavers and rid of the artistry in human error, to create intricately uniform details of leaves and flowers into the tapestry of fabric. Man and machine, Babbage wrote, lead to the economy of human time. Only a tool, a technology, could do the work of many and increase the number of things made. Soon, new divisions of labour would become possible, the breaking down of tasks of both the human hand and mind, where the constant repetition of the same process would produce in the worker ‘a degree of excellence and rapidity in his particular department’ which could never be skillfully carried out by any single person.2

Time was once an elastic measure, embedded in social relations, where the cycles of the sun had dictated the hours of the day and where the waning daylight of winters shortened the communal work of the harvest. By the mid 1800s, a new sense of time emerged from the textile mills, creating new rhythms that regulated industrial life. Time was now quantified and incremental, its economy dependent upon on the repetitious rhythms of the body’s same movements over and over again on the assembly.3 It had become abstract, a scarce commodity, and an indication of when one was free, or when one was not. The historian E.P. Thompson also observed how labour transformed our inner schema, or apprehension of time.4 People were now workers or employers who could not escape the anxieties of industrial time, as it appeared in every aspect of public life, from the church clock, clocks in town markets and squares, the grandfather clock inside the home, the pocket watch that hung from bodies. Industrial time even rang as sound, from the morning bell to curfew, the sound of the whistle and time stamp, the tick tock of hands that divided hours to minutes to seconds (today it glows through our iPhones). Work and life was neatly demarcated. Time had become the shackle of all workers.

On the assembly, industrial time subjugated worker’s movements, demanding a synchronicity that was anathema to the human body. Charlie Chaplin mocks this subjugation in workers’ movements, whose gestures were meticulously adjusted to working specific parts of the assembly. Chaplin mimics the fragmented movements – his tightening of screws carries out in stutters, hiccups, jolts and jerks, in staccato bits of movement.5 We can’t help but laugh when we see his inability to keep up, throwing chaos into the machinery and making it explode. Chaplin’s funny movements liberate the working body, reminding its audience of human capacity and experience. In the philosopher Walter Benjamin’s commentary on the film, he argued that laughter was critical to bringing us back to our senses and out from of our numbed alienation in time, labour, and capital. Film and the moving image of the body on screen could powerfully mirror back to us human experience, counteracting the body’s systematic subjugation in labour through comedy.

Today, time is no longer just the wage clock and time stamp – in global capitalism, it is now a never-ending twenty-four hour global day in the ‘just in time economy.’ It’s synchronisation globally has produced a new world of coordinated logistics with automated ports, timed with the movement of ships, cranes, planes, and millions of dock workers, port workers, seafarers, warehouse workers, truckers and rail workers who ship as many as four hundred packages and fill six million containers at any given moment.6 The build out of ports in the 1980s lead to the rise of the transnational corporation, producing both a retail revolution in the U.S. and Western Europe and the world’s biggest factories in history in Asia. Inside the world’s global garment factories, the measurement of time on the assembly was further fragmented into some hundreds of tasks, where workers’ bodily movements were punctiliously measured as ‘standard allowed minutes.’ Detailing the number of operations, length of seams, fabric type and stitching accuracy of workers performance, these new metrics estimated the exact time and cost of making a garment, dehumanising labor to determine ‘factory capacity’ for global companies.

All this takes on new meanings and scales when it comes to Made in China. The U.S. and Europe’s largest retail companies manufacture in China’s newly built factories in special economic zones that attract foreign investment free of any regulation. This was part of the Open Door Policy by Deng Xiaoping that resulted in the privatisation of all state-enterprises and industries in China. By 2005, most everything Americans bought and wore — sneakers and sweaters, electronics, toys, Christmas decorations, and furniture — was marketed by four-lettered global companies such as NIKE, IKEA, APPLE, ZARA and manufactured in China. Of the 130 million migrant workers who toiled in these factories across the Pearl River Delta, from Guangzhou to Shanghai, 6.5 million were garment workers alone. Labour powered factories so large, that as many as 400,000 workers could be found working in one building alone.7 For the last three decades, these migrant workers left behind their villages to head for the city to service China’s headlong rush into global economic supremacy. They also left behind their children with grandparents, along with their youth and vitality. Today, migrant workers still consistently work twenty-nine days for fifteen-hour days straight. They will take the four-day train ride to their homes, once a year, to celebrate one holiday – the New Year.8

I have learned that this is what Capital with a big C, through labour, can now do. For the last three decades in the U.S., Wal-Mart in partnership with Made in China allows Americans to Make America Great Again, as one can now feel wealthy by affording cheap food, clothing, things of all kinds despite one’s lack of healthcare, job security, a free education, housing and public transport. Nevertheless, this kind of capital can give us jeans that are rhinestoned, sandblasted, embroidered, sequined, silkscreened, tasseled and frayed. We can mine for tantalum, gold, tin and tungsten as far as Cerro Rico, Inner Mongolia, and the Congo for those irresistible metallic rose gold iPhones.9 We can order formula and diapers on JD.com and UPS.com and have them dropped off to us by drone in some rural town.10 We carry on Twitter culture wars and learn from YouTube videos, whose algorithms lead us to makeup tutorials and white supremacist fringe communities, all in one go. We have TikTok memes and musers entertaining 500 million monthly active users who boast of one billion downloads. According to philosophers, we’ve become the digital swarm that rages on, where each post, tap, click, swipe, zoom or like is a vote to be tracked and monetised.11 The mature among us warn of our suspended senses and the general distraction that is now our daily affective condition. We tell our young that they have yet to wake up, though in the reality of this 24/7 cycle the young have not even gotten the chance to fall asleep.12

The protests in Hong Kong continue to swell because the young see in China a factory for the world.13 They understand that our fast-fashion, sneakers and metallic rose gold electronics have produced wealth for a few, and built only the backs of low-waged rural migrants without unions, a free press, or rule of law. In this city, the booksellers continue to mysteriously disappear. I’ve learned that if the protests had been in Shenzhen or Shanghai, it would have been another Tiananmen. In this hyper life of capital, the young and old alike seek out the meaning to all this – how to radically break down the barriers of work and life? How to re-enchant this social world, reactivate and recover our sense of collective agency, find meaning in the interstices of time? We are only human when our instinct tells us to seek escape from the homogenising processes of these modern times.

I think of all this as I pack up my belongings — all the stuff of my kids and family — from a rotting old house in the Hudson Valley to another one in the woods. I feel so far from the factory behemoths, of men and machines and industrial histories that I have spent my career learning about from textbooks. Here, I am reminded of a different kind of time in capital – the biological time that naturally resists it – where the crevices of days, one’s relationships with people and things, only heighten the awareness of mortality. Not men and machines, I think, but rather women and children in the kind of work that doesn’t seem to fit so neatly into the assembly or the measurements of some industrial clock or twenty-four-hour work day. This is an imperfect and preindustrial sense of time — of mothering and daughtering and preserving human life — which forces one to abandon any kind of synchronicity. The labourers were out in the fields, the factories and offices, or even out in the streets striking, but only because the women were at home, carrying out the invisible work taking care of the children and the elderly. Maintaining life is both hard labour and creative practice, as one in the same, continuing the next generation of workers while burying those who have perish after a lifetime of toil.

In the middle of my move, I pack boxes of things and throw other things away. So many things are thrown out. The opening up of closets, trunks, and boxes reminds me of the basement closet I hid in as a child, while my parents worked in the adjacent room painting cheap costume jewellery under fluorescent lights. The clothes smelled of mothballs and mildew, damp wool and old fur. Its rafters held my mother’s secret stash of cash and bills. The clothes in this closet — of dresses and jackets — were worn so long ago, pictured only in faded photos, worn on bodies before having children, when my mother was a different person, a young working woman in the city making money for only herself. Opening up of closets, like the one of my great aunt in her tiny West Village studio apartment, where she packed away a lifetime of small collected things that she never again revisited. After my great aunt passed, I found in her closet a pair of worn shoes – I can see them in a photo from when she was twelve. A small beaded purse wrapped in its dusty original tissue paper. An album of wedding photos in a six-week marriage I had never known about, with her husband cut out of every picture. Here is another photo of my great aunt in her in cap and gown. While the war raged on in her home country, while my fourteen-year old impoverished father was digging ditches to bury his family, her family’s wealth allowed her to escape to Paris and then to New York. On my gloomiest of days, I still walk by her old apartment thinking of my mother, my father, and her.

I am throwing out the clothing of my children, full of stains that make none of it worth saving, all evidence of their world of hard-play. Their clothes turned tattered from climbing, from throwing mud, getting snagged on trees and bushes, elbows and knees completely worn out. I ask my daughter to wash off the dust from her once shiny and new black boots – the black boots that the ninety-three year old horse lady who lives down the road from our new place told her was the most exciting thing for her to see and smell. ‘How many years does a horse live?’ I once asked the horse lady, only for her to quickly snap back, ‘but how many years for a human?’ making me think about this comment all summer long. On this hot summer day, I fish out from my closet my wedding dress only to find it with different coloured yellowed sweat stains on the bodice and deep black and grey mold mottled on the bottom. Though ruined, I save it not for my daughter but for the relief it brought for my mother, in hiding her shame for my six-month belly buried underneath these yards of lace. There’s a pile of old jeans and old bed sheets to wash too, though I know the bloodstains are permanent. This too reminds me of a different kind of time lived, which will soon enough arrive and be understood by my daughter. I am packing things up and throwing things away – this accumulation of obsolete things, used up, broken junk, which only I give my arbitrary value to. I think of Primo Levi in the camp, telling the story of survival from just a few key possessions — a spoon, a bowl, a piece of string, a button, a tin cup — which he also said put one at risk of getting killed.14

For some reason and at this age, I know these things — that these things made by others who have traded in lives and labour and that I have accumulated in one house — that sadly, none of this will even matter. That I have been in the houses of ninety-three olds — capsules of another time in beauty — with all those things now just rotting away, a burden for her children to clean out. When we stand in the horse lady’s house, my daughter only points out the birds’ nests in the rafters, a thing of beauty among the decay. I am moving out of my house so that my eighty-three-year old father will not hesitate to visit me — I bought a house without any steps — since, as he reminds me daily, I only have two more years with him yet. Eyes that can no longer thread a needle, ears hard of hearing, bodies that work to breathe and move forward. The horse lady will be gone. The terror that my parents will die soon, that I have just a few more years with my own children, before long they too will leave me for good. Will they remember how many times I dressed them, fed them, loved and cared for them? I have already forgotten this with my own parents. In the regulated and regimented hours of present day, I seek out a time and a place to understand these ungoverned thoughts.

Clothing and capital I have learned through grand structural histories of ‘the way things work,’ explained to me as men and machines and assemblies. And yet here I am, packing it up and throwing it away, thinking of the workers, my mother, my father, my children, my great aunt, what Primo Levi said about a spoon and a cup. These days, I can’t shake that ghostly photo of discarded clothes in dry arroyos abandoned by migrants in the Sonoma desert.15 I think of the images of garment workers’ daughters in cramped apartments in Chinatown.16 I’ve been consumed all summer by that photo of a baby held by a father, drowned in the Rio Grande — the very same river my mother-in-law was born next to — face down in the water.17 Only the black cloth of his own T-shirt prevented his baby daughter from washing away. Such anguish I feel these days, when thinking of clothing and capital. In between days, I crave something beyond formal histories and seek closets as interstices to history. These things I look at and pack up and throw away have me thinking of all these lives lived. There seems to be no economy to any of this. There is only survival, the maintenance and preservation of life, and the communal remembrance of it.

Dr. Christina Mooon is an anthropologist by training and an assistant professor of Fashion Studies in the School of Art and Design History and Theory at the The New School for Design in New York.

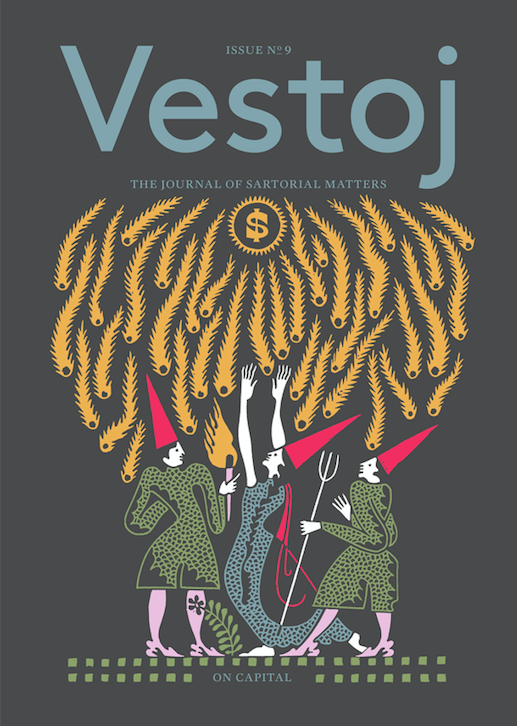

This article was originally published in Vestoj On Capital, available for purchase here.

C Babbage, On the Economy of Machinery and Manufacturers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. First published in 1832. ↩

Ibid. ↩

E.P Thompson, ‘Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism’ in The Making of the English Working Class, London: Victor Gollancz, Ltd./Vintage Books, 1963. ↩

Ibid. ↩

W Benjamin, ‘The Formula in Which the Dialectical Structure of Film Finds Expression’ (1935) trans. Edmund Jephcott and Harry Zohn, in Benjamin, Selected Writings, vol. 3, ed. Michael W. Jennings et al. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002. ↩

See A Madrigal, ‘Containers.’ Audio blog post. Episode 1: Welcome to Global Capitalism. Medium, 7 April 2017. Web. 28 July 2019. ↩

Freeman, Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018. ↩

The Last Train Home. Directed by Lixin Fan, Zietgeist Films, 3 September 2010. ↩

B Merchant, The One Device: the Secret History of the iPhone, New York: Bay Back Books, 2017; L Browning, ‘Where Apple Gets the Tantalum For Your iPhone.’ Newsweek Magazine, February 4 2015; R Mead, ‘The Semiotics of “Rose Gold,’ The New Yorker, September 14 2015. ↩

J Fan, ‘How E-Commerce is Transforming Rural China,’ The New Yorker, July 18 2018. ↩

B Chul Han, In the Swarm: Digital Prospects, Untimely Meditations (Book 3), Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2017. ↩

See J Crary, 24/7: Later Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, New York: Verso, 2013. ↩

A Weiwei, ‘Can Hong Kong’s Resistance Win?’ New York Times, July 12 2019. ↩

P Levi, Survival in Aushwitz: If This is a Man, Orion Press, 1959. ↩

R Barnes, ‘Debris Field Left By Migrants on U.S. Side of the Border, 2012.’ http://www.richardbarnes.net/state-of-exception. ↩

C Chang, ‘The Daughters of Garment Workers,’ USA, New York City. 1996. https://pro.magnumphotos.com/Asset/-2K7O3RC16RC.html ↩

J LeDuc, Photo of the bodies of Salvadoran migrant Oscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his nearly 2-year-old daughter Valeria, on the bank of the Rio Grande in Matamoros, Mexico, trying to cross the river to Brownsville, Texas, June 24 2019. The Associated Press, originally published in La Jornada. See https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/jun/25/they-wanted-the-american-dream-reporter-reveals-story-behind-tragic-photo ↩