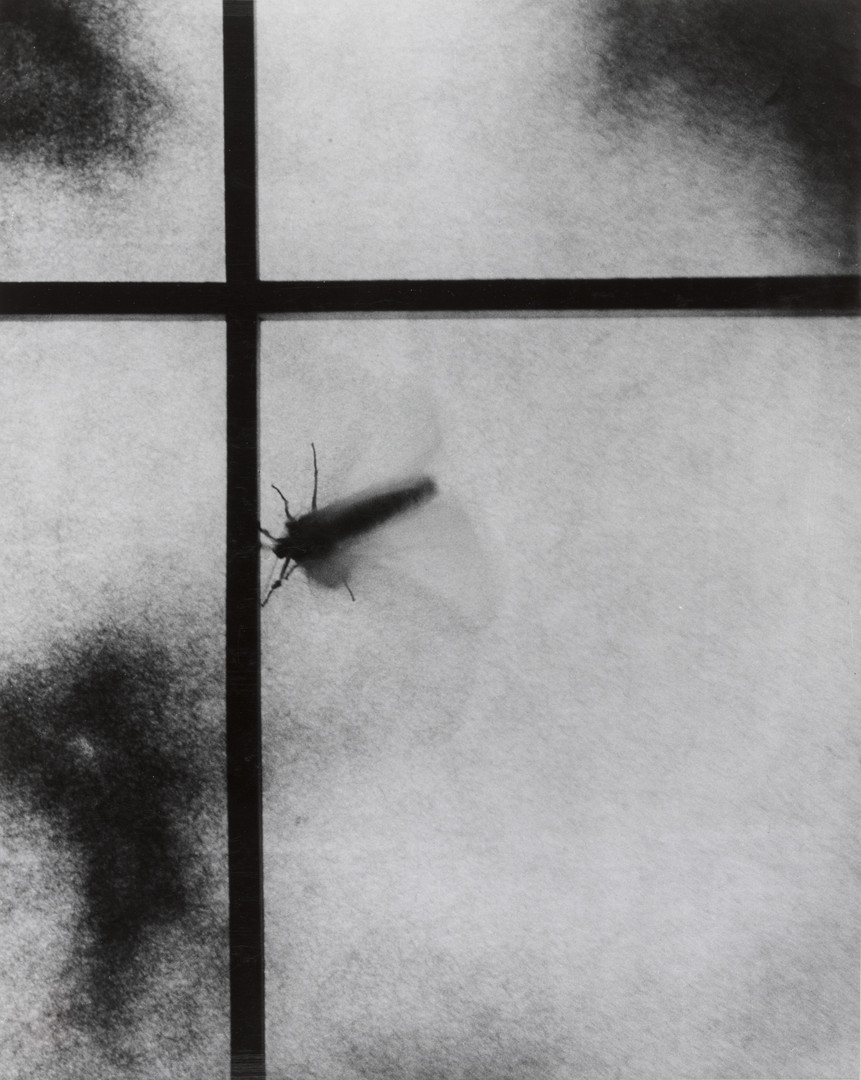

If this is a reckoning, let it start with a moth. With two moths. With three white paper moths pinned in place or time. With uncountable numbers of moths, cascading forth from long-closed attics (or wallets) or crumbling to powder across the centuries, oh so neatly labelled, in the drawers of museums.

The first moth is small and brown against the sallow textured wallpaper of our bedroom. Upon seeing the moth, my priority is to remove it. It is within a foot of my wardrobe and I am anxious. There are, as far as I can tell, two possibilities: the wardrobe, with all its irresistibly delicious woollen goods hung up or folded away, is either the moth’s destination, or – worse – its point of origin. Either it comes to lay eggs upon my clothing or it was itself born here and my cherished jumpers and trousers and jackets and coats have by now provided this moth and others like it with vital sustenance in their formative moments. Either way, moth, I’m afraid your time is up.

I do not look closely at the moth. I do not examine its wings or measure its antennae or admire the jaunty crook of a leg. I do not pause to imagine how moths encounter the world. Instead, I fetch the toothbrush glass from the bathroom and, with a firm but gentle sense of purpose, I place it over the moth. I hold the glass in place with my right hand and, with my left, reach across to the chest of drawers where lies my passport. Brexit blue, made in Poland and completely unused in the year and a half that I have owned it, the passport has travelled further in its making than I have with it. Yet, slim and stiff and portable, it makes for an ideal moth relocation utensil. I slide it between the rim of the glass and the textured wallpaper, careful not to crush the moth or inadvertently release it. With the moth now safely housed within the glass, I make my way downstairs, still paying little attention to the creature itself, beyond the fact of its presence within the glass and the need for its prompt removal. I open the front door, and release it into the night.

And now, moth rescued/evicted, I permit concern to give way to panic. What has happened here? I must hunt the wardrobe for any trace of tell-tale sheen, any pale wriggle of moth, any thread of glistening trail down a sleeve or trouser leg, any fine quenelle of wool about the cuffs. I must assess the damage and I must do so in order of priority.

First, my tweed suit, the only item of clothing I have ever had made for me. It’s Harris tweed, coarse and spongy. Really it’s coat-making fabric but it works somehow. Ça tombe bien, cooed the tailor at the first fitting. ‘That works well,’ but also ‘That falls well.’ The line of the lapel, the crease in the trouser, just so. The fabric is predominantly dark green with shades of blue and a subtle check overlaid in ochre. Up close, it reveals a dappled panoply of purples and crimson, yellows, blues and bright white. It’s a cliché to compare tweed to the landscapes from which it originates, but really there is a whole world of wonder in this fabric, a lustrous, sad vanished world of beauty and delight, nestled all in there among the dark fibres. When I first wore this suit on the Paris metro, I became so entranced by the colours magically revealing themselves as if on long moorland walks across my own thigh that I forgot for a time where I was, missed my station, and was embarrassingly late for a meeting. ‘Sorry to keep you waiting, I was staring at my own clothing.’

I realise I’m holding my breath as I unzip the suit-hanger, acutely aware of a myriad of possible moth entry points and taut with anticipation of the subtle delicate carnage I might find within. I check every seam and surface, jacket and trousers, inside and out. If you’ve touched this suit, moth, I’ll… The suit, is, I think, clean. But, upon tweed as rich with life and colour as this, how could I ever really know for sure. Panic begins to subside. Anxiety lingers.

Next I take out an ancient overcoat – made for HI Jeffreys by B Bernard of Great Marlborough Street in 1929. It is a splendid thing, venerable, preposterously heavy. It is like wearing a carpet – thick and brown with an unusual diagonal stripe pattern in reddish-purple. Despite multiple adjustments, multiple attempts to take ownership of this coat, it remains the property of my great grandfather. My father had it shortened by six inches or so. I had it taken in significantly at the waist and had a button at the throat shifted too, but it remains a little large for me around the chest and shoulders. I don’t mind. I know I’ll never quite be the owner of this coat. It will always remain something that I have received, a gift from a man I never knew.

I realise, as I’m writing this, that I don’t even know what his initials stood for. Henry Isaac, my father tells me later. English. Jewish.

I think of Maria Stepanova who writes of literature’s ‘guttering flame,’ kept alive by Russian Jews in the 1890s as so much of the world fell towards a frenzy of nationalism. I think of my own family’s past, about which I know so little. I think of those old prayer books, inscribed in Hebrew, a family heritage hidden away in the backs of drawers and wardrobes and perhaps best left there. My brother is interested in excavating all this – ‘the keeper of the flame,’ my cousin put it as he handed over a trio of chunky old photo albums. There are photos of Henry Isaac in there among the youthful swell-time grins of the 1930s, the privileged classes enjoying their privileges – all the more enjoyable for being, in retrospect, so very precarious.

Unlike my brother, I’d prefer to leave the past there, closed up in old books, something to imagine and not to know. Or perhaps I don’t care that much, or perhaps I daren’t admit to caring. This way, my family exists in the objects they left behind. Clothing enables a repurposing of memory in a way that photographs perhaps do not. And the moths will eat all memory in the end.

As the coat nears one hundred years old, it is in need of some love. The fabric is thinning in places – near cuffs and around pockets. Black cotton threads have come loose about the button holes. If you’ve touched this coat, moth, I’ll… nothing. The coat, is, like my suit, clean.

Next I take out my morning suit – made in 1938 by Airey and Wheeler of 129 Regent Street for my grandfather, GM Jeffreys. Gordon Michael. English. English. The jacket is a beautiful thing: dark and matte and felty black, quilted interior, swooping lines of tails. Two rear buttons a legacy of some long-lost functionality. Like an appendix, a vestigial organ of tailoring evolution.

I recently had the sleeves lengthened by an inch and a half, the beautiful stitching around the (non-functioning) cuff buttonholes replaced with a perfunctory line by a person who did not have the same skills or time or who was simply working for a client (me) with significantly less money than the original client (my grandfather). The trousers have been widened at the waist and taken in again. The legs have been shortened, then lengthened again. The waistcoat, dove grey, double-breasted, is oddly backless – compensation perhaps for the warm weighty heft of the trousers. I examine it all closely with a sense of trepidation, And, sure enough, the tell tale signs of mothery.

Three slim white curling tubes like tiny cannoli made of petals, pellets of the fabric, gathered into grains of rice. Then, crawling slowly across the striped surface of the woollen trouser fabric, a tiny white larva, like a maggot. Then a second. Then a third.

*

A few days later, I remove the three-piece morning suit from the bottom drawer of the freezer. There are shimmering trails along the trousers – tracks caused, I imagine, by those little larvae seeking their freedom. I’m sorry, I say to them out loud or nearly out loud. But I don’t really mean it.

I associate moths with the destruction of clothing. But the relationship between the two is of course also creative. Moths have been making their own clothes long before humans got involved and moth larvae have been farmed for their silk for thousands of years. The moth, like the butterfly, is an agent of radical change. The moth transforms via its clothing. Shy, it first builds itself a dressing room.

But I’m afraid there can only be one species dressing in this house.

I make a visit to one of those shops that functions like a staging post on the journey from factory to landfill. Row upon row of hooks and screws, pots and pans, cutlery and lightbulbs, tupperware, tablecloths, tools and glues and tapes and paints, printer paper, luggage and, my favourite, a wide selection of plastic bins – objects for the temporary storing of rubbish which are themselves destined to become rubbish. Matter is matter out of place. Everything in here is pointless yet everything will be needed by somebody at some time. The shop was one of the few permitted to remain open during the lockdown of 2020. Food: essential. Booze: essential. Bleach, batteries and bulldog clips: all equally essential.

I purchase a selection of products designed to eliminate moths. I’ve tried the gentle approach – sachets of lavender, miniature globes of scented sandalwood – but they never really work. Now, my wardrobe is to become a fortress, impenetrable to moths, guarded at all hours by the unsleeping power of transfluthrin, its toxic stench impregnated into paper strips, purple pouches and capsules wrapped in plastic. The wardrobe is filled with chemical agents that will seek out and interrogate any potential traitors, fifth columnists moth sympathisers that somehow found their way in or were lurking here, sleeper agents, all along.

The result is a hot, close acrid smell that hits the roof of the mouth, lingers at the back of the throat and triggers my wife’s migraines. It lasts for weeks, even seeps into my dreams.

*

Next to me, as I sleep, are three other moths, each one quite white. They form a row, mounted on a ground of pale grey inside a white box, sheltered behind UV-protective glass. These moths are not really moths but moths made from paper by the artist Laura Culham. They are the first work of art I ever bought.

Culham’s work combines sensitive attunement to the beauty of the mundane with a love of paper and of trompe-l’oeil. Almost everything she does is small, delicate and incredibly time-consuming. She has recreated found fragments of blue and white china, made blades of grass and ears of wheat or corn out of paper, produced exquisitely delicate pencil drawings of water or spilled ink, and crafted a dozen perfect paper sculptures of scruffy nameless weeds.

These moths, a triptych of sorts, hang on the wall just a few feet from my wardrobe. I saw a version of the work in the artist’s degree show and asked if she could make me something smaller – three moths instead of eight.

Each is a precise, laborious recreation – a fixing in time, redolent of all those entomologists obsessively pinning the world in place, one specimen at a time. But Culham’s devotional care is creative not conservative. Like her other works, Culham has not named these moths. Every work is untitled. There are no labels, no bipartite Latin names, and each moth remains, as a result, anonymous. I don’t even know if these are modelled on specific moths or imagined, generalised composite moths. It hardly matters. Here they are individuals, without the need to fix with terminology or the steel pin of scientific research.

Left to right, they lie: the first on its front, wings down, thorax fluffy; the second on its side, a mothy profile with antenna swept back like plumage, forewings horizontal, hindwings down, and, just there, a hint of proboscis. The third lies on its back, wings behind but curving up and forwards, antenna twirling out like moustachios. It’s legs are crossed in front of its body as if atop the tomb of some medieval knight – dignified, but also a little silly. They are, together, a study in delicacy. Those frayed edges, those finger-furrowed wings. Moth wings are often described as papery. Here the paper is as fine as wing.

As I’ve moved, these moths have moved with me: carried from flatshare to flatshare in Hackney and Bethnal Green, to Stoke Newington, back to Bethnal Green, into storage in my parents’ garage, and now, most recently, here to Edinburgh. Many moths live only a few days, some up to a year. These moths are a decade old now, the only signs of age a loosening of part of the paper mount and a slight dark scuff to the bottom of the frame. The moths themselves remain pristine – frozen in their papery whiteness.

Colour rarely features prominently in Culham’s work. But the whiteness of these moths is especially striking – as if all the colour and pattern of life has been bleached from the world. Texture is all that remains. I keep looking at Laura Culham’s paper moths and I start to think about the centrality of death in the scientific study of life: so many moths and butterflies killed in the name of learning or progress or love. The heartless dead sterility of knowledge, the desire to isolate, fix, kill. What kind of understanding is an understanding generated through destruction? When a need to know slides easily into a need to have, possess, destroy through having and possessing?

As I look at them now, I feel a desire to reach out and touch, to feel, just to know that it feels like to feel. But the glass prevents you. I think about that desire to touch, which is maybe never far from a desire for ownership, control. Owning the work, I forget, but also I remember art’s Faustian pact with private property. Commodities, commerce, scarcity, exchange. I picture the powerful hand of modern science which, like Lennie from Of Mice and Men, crushes to death the fragile thing it loves. I think of something Rupert Sheldrake once said or wrote – that people come to biology through a love of living animals but swiftly find that, as a scientific discipline, it mostly involves imprisonment, death and dissection. ‘Science is how capitalism knows the world,’ wrote Rebecca Solnit. It is no coincidence that the most biodiverse places in the world are those that modern, Western science has not got to yet.

The moths appeal and resist. You can only look, right up close but always through a barrier. This is work that walls itself off from the world – the same world (or is it) that was attended to so carefully during the time of its making.

The glass makes visible this walling-off, so carefully protective, but of what? Some paper, in the end, an exquisite non-encounter between human and nonhuman. The real thing, this moth, was just over there, six feet away, on the striped wallpaper, and I let it go, freed it, exiled it, hardly looked at it as I did so. And then I froze all its brethren to death. Interspecies cohabitations are easier to read about than to live. Objects are simpler to be with than people and sometimes they even mean more, matter more. I’m sorry not sorry. It’s hard to say when it’s hard to know. And perhaps Culham’s work is a memorial to those moments of impossibility, a careful, slow meditative attention that is bound, in the end, always to come up short.

One day soon the moths will return, slowly at first, then all of a rush. From art to dust, from clothing to food, from larvae to imago, and all the way back around: a wearing down, a crumbling, a slow, sudden transformation from one life to another. Oh so fleeting. Then, the moment you fix a thing in place, and lean back, that’s the moment you know, just then, it’s gone.

Tom Jeffreys is a writer living in Edinburgh, mostly covering contemporary art, particularly work that engages with environmental questions. He is the author of two books: The White Birch: A Russian Reflection (Little, Brown, 2021) and Signal Failure: London to Birmingham, HS2 on Foot (Influx Press, 2017).