Simone de Beauvoir once said that ‘one is not born a woman, but rather becomes one,’ and many would argue that the same could be said about being a man. The social nature of masculinity is a pattern of practice, and one rife with complexity and contradiction. Today, it seems more apt to talk about ‘masculinities’ in the plural, to underscore the many ways in which one can be a man, or become one. What we have thought of as ‘masculine’ has changed considerably during different historical periods and inside different cultures, and the social position of masculinity has helped shape not just the gender order by which we continue to define ourselves, but also a hierarchy of masculinities that encourages certain ways of being a man over others. What we consider masculinity is sustained by men, but also by women: how women interact with boys and men continues to have a considerable influence on what we regard as masculine. While the concept of the human mind as a tabula rasa is no longer fashionable, and most today agree that the answer to ‘what makes a man’ lies somewhere between the influence of nature and nurture, the society in which we live continues to have a considerable and ever changing effect on how we perceive ourselves.

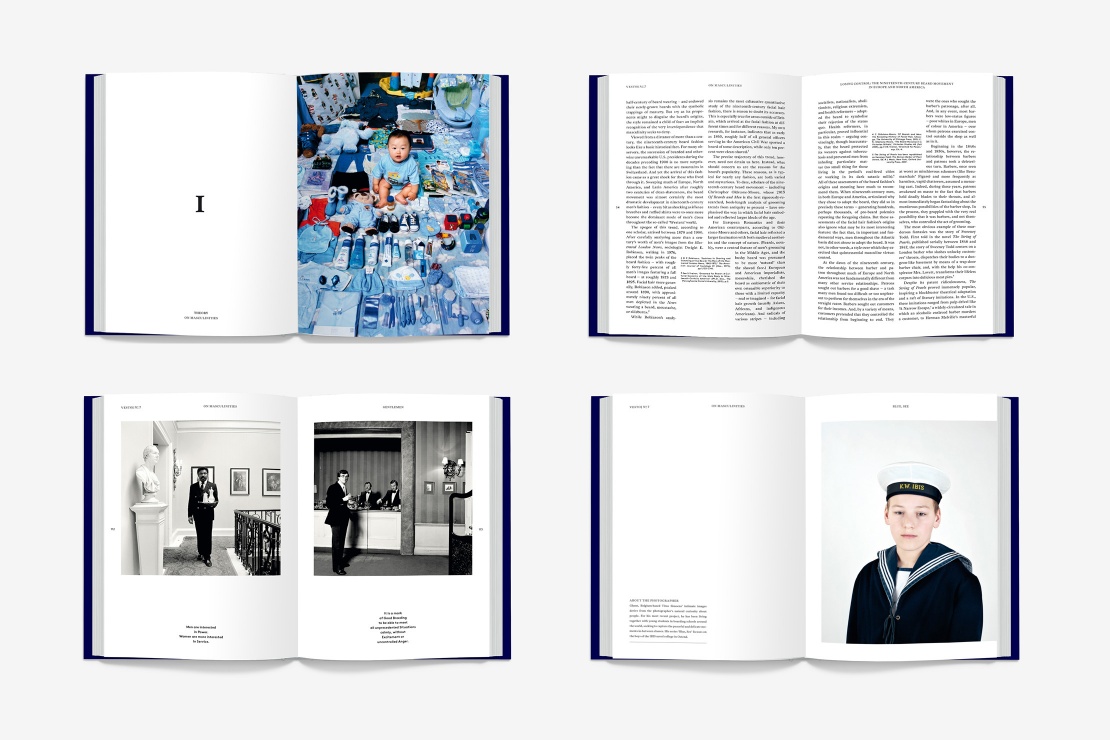

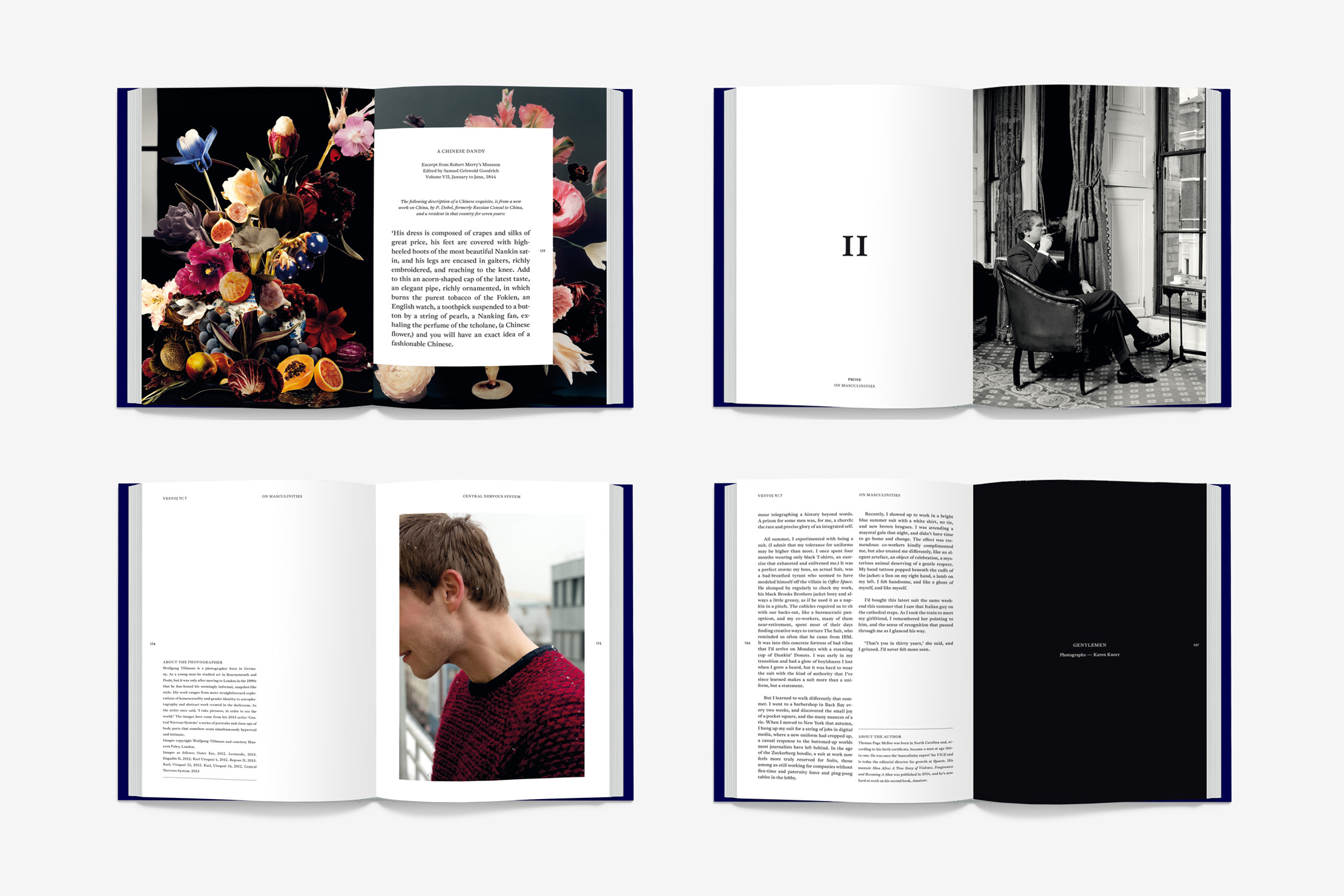

There is of course no natural link between a garment and a certain gender, but nevertheless sartorial transgressions of our moral and social codes remain rare. A telling example of how we as a society and culture value symbols of masculinity is the adoption of trousers by women in the West in the early twentieth century. Though women had to face ridicule and resistant legislators (it took until 1993 for women to be allowed to wear trousers on the U.S. Senate floor) we have, after all, had an easier time adopting these, and other, masculine coded garments than men have had embracing potent feminine symbols. Women’s espousal of trousers may have represented an important readjustment of the definition of femininity, but it hasn’t necessarily led to a change in the existing balance of power. ‘Default man’ is still at the top of the food chain, and men in skirts should be prepared to field questions about their masculinity.

How to be the ‘right’ kind of man is a battleground for many, and some might say that when it comes to manhood, man is warden and prisoner alike. Hegemonic masculinity stipulates how to act, dress and talk ‘like a man,’ and men who don’t want to risk being shunned have to position themselves in relation to it. Redefining this masculine ideal, and the power, legitimacy and privilege that goes along with it, takes time and concerted effort. Alternative masculinities are regularly subordinated to uphold the type we have become used to thinking of as ‘heroic:’ stoic, tough and honourable – the type that wears the trousers, the type that doesn’t cry. Considering masculinities in the plural might be one way to better understand how dominant masculinity is constructed, and why alternatives are so often rejected in order to uphold its status as ‘the real thing.’

What, then, is the difference between maleness and masculinity? To the Romans, the separation between virility and manliness was crucial. To possess virilitas, a Roman had to display, not just shrewdness and strength, but also self-control. Being virile, as opposed to being male, was a learned quality. Today we no longer refer to an accomplished man as ‘virile,’ but in many ways we continue to think of male identity as a combination of discipline and force. Pick up a copy of any men’s magazine for further proof: every tip about how to get the right abs, money or women seems to hinge on the notion that successful men control others by controlling themselves.

Lately there have been cries about masculinity ‘in crisis’ and the emergence of a ‘new man’ – an idea that the fashion industry in particular has been quick to capitalise on. What should this new man wear? In a shifting landscape where masculinity is being supplanted by masculinities, surely another wardrobe is being called for? But while men try on pussy-bow blouses and extra-long sleeves, sceptics point out that the catalyst for this plethora of new looks might be more closely related to the ever-increasing commodification of everyday life and advances in marketing and advertising, than it is to any kind of new man.

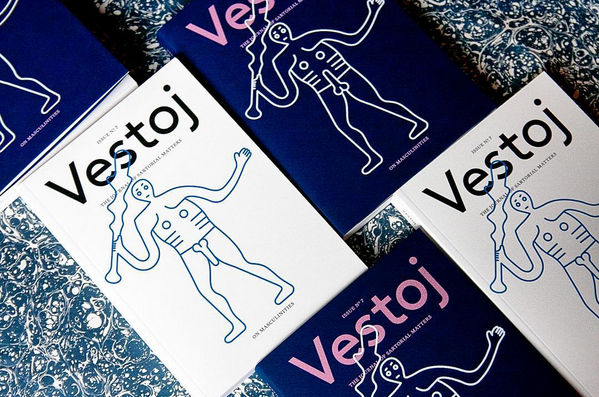

Whether modern masculinity is a construct, and men’s fashion a tool intended to keep the wheels of consumption turning is one of the questions we would like to raise with this issue of Vestoj. But we also aim to explore the making of masculinities and the experience of men’s bodies, as well as how people who identify as masculine are portrayed along with how they choose to portray themselves, both in public and in private. We will look at how we express masculinity through appearance, and how changes in fashion have been influenced by a perception of gender constantly in flux. We will ask why blue is for boys, how machismo affects fashion and why it’s so hard to shake the whiff of absurdity that stubbornly clings to male pin-ups. Typically male coded garments will get a close reading, and we will apply an ethnographic perspective to how men shop. All the while, we will ask, in as many ways as possible: what do we mean when we say ‘the clothes make the man’?

In his Symposium Plato wrote that we were all hermaphrodites until the gods decided to split us in two. That men have feminine traits and women masculine ones has entered the mainstream by now, but even so, when it comes to our appearance we continue to favour convention. Curiously, even unorthodox displays of masculinity ultimately point to their deviation from the norm, and as such they reinforce the standard. Even the man in a skirt is always already not a man in a suit.

Texts by

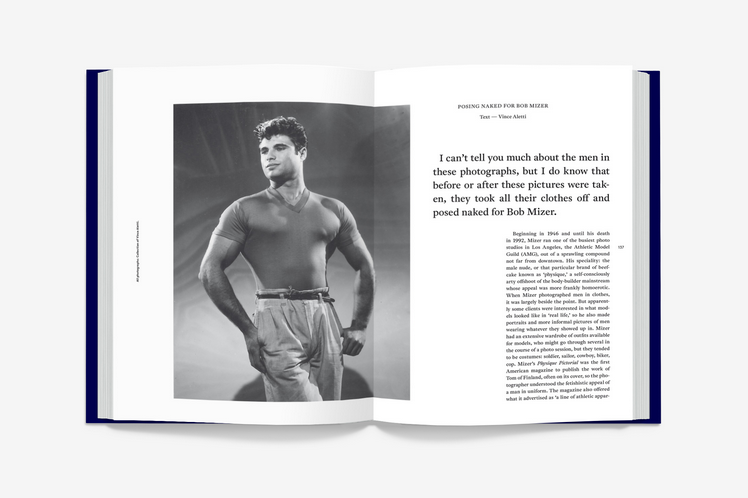

Jo Barraclough Paoletti, Victor Rios, Patrick Lopez-Aguado, Johannes Lenhard, Sean Trainor, Annebella Pollen, Christina Moon, Shaun Cole, Thomas Page McBee, Claire Marie Healy, S.G Goodrich, Christopher Breward, Vince Aletti, Alice Hines

Interviews by

Anja Aronowsky Cronberg

Fiction by

Mark Twain, Sloan Wilson, Nate DiMeo

Visuals by

Jason Fulford, JeongMee Yoon, Camilo José Vergara, Titus Simoens, Karen Knorr, Wolfgang Tillmans, Scheltens & Abbenes, Bob Mizer, Pawel Jaszczuk

Design by

Studio Blanco

All images courtesy Studio Blanco