This is a response to the article ‘The Maddening and Brilliant Karl Lagerfeld’ by Andrew O’Hagan, published in T Magazine, October 12 2015.

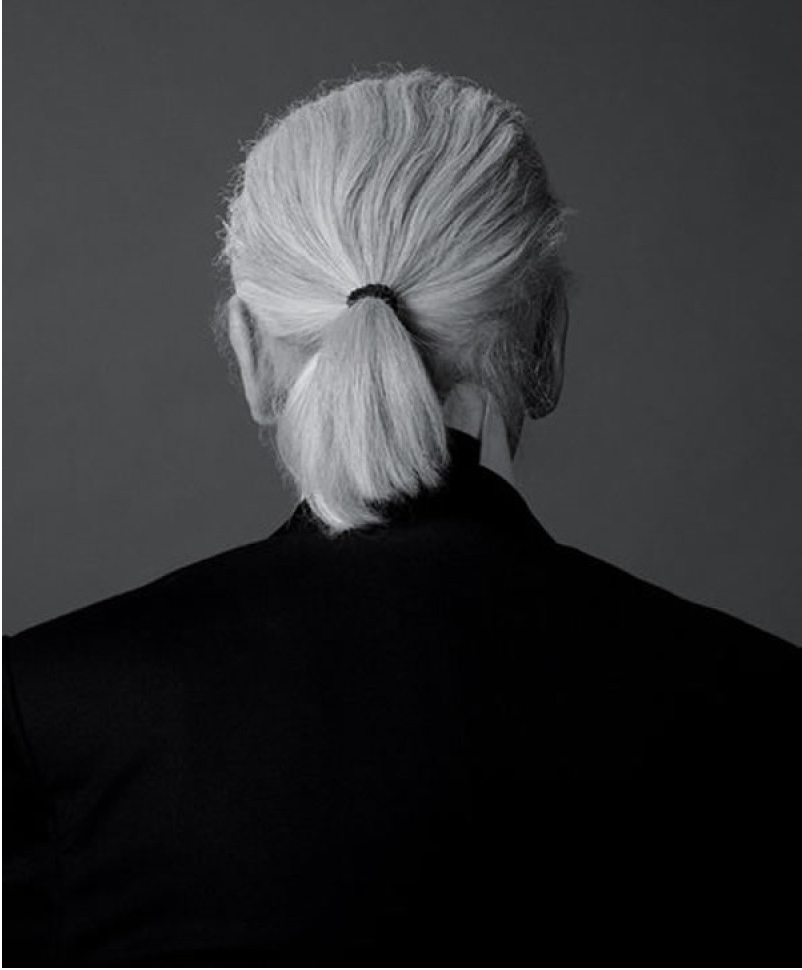

ON THE COVER OF the recent October issue The New York Times’ weekend supplement, T Magazine, Karl Lagerfeld’s profile looks out like some sort of modern renaissance bust. As one might expect, his severe white collar and dark sunglasses are firmly in place, as is the white ponytail. The cover is one of a series of six released for the issue, and accompanies a feature article inside on the designer. It’s a long-form profile and interview by Andrew O’Hagan that gushes over Lagerfeld, depicting him as the most important designer of our time, or in the author’s words: ‘fashion’s one and only.’ The high praise of the designer could be mistaken for an extended press release and might be construed as another example of the failure to present balanced and analytical coverage on fashion in mainstream media, particularly for a publication like The New York Times.

The interview itself takes place between the designer’s home in Paris and also in Seoul, where he is preparing for a Chanel presentation. O’Hagan opens the article and interview with a quote from Marcel Proust’s famous sartorial descriptions from In Search of Lost Time – a book that illustrates fashion as ‘not a casual decoration alterable at will, but a given, poetical reality like that of the weather.’ The preface leads into the sweeping generalisation that: ‘It’s about a hundred years since fashion took its place alongside literature, painting and music as a way to look for the social essence of one’s era.’ Fashion, which as we know is older than this, is immediately marginalised from the outset as a lesser, younger form of the arts. This is a statement that is reinforced in the intellectual banter about literary and cultural figures that ensues, an effort to add some sort of cultural capital to Lagerfeld and reassure us of his significance as an ‘intellectual designer,’ despite being embedded in the world of fashion.

Andrew O’Hagan is a Scottish novelist and non-fiction writer with seven books published and one Booker prize under his belt. His credentials as a writer suggest that the editorial choice of him as author feeds into the overarching semblance that this article will be looking at fashion seriously. This notion is reinforced by Lagerfeld’s cultural dexterity, which is constantly reminded to us throughout the article – from the setting of the designer’s Paris apartment with its ‘Art Deco ambience’ and ‘candle-scented air,’ to the art (a Jeff Koons sculpture) and its book-lined walls (‘the room is all about the books’). O’Hagan’s conversation with Lagerfeld begins with the name-dropping back and forth on twentieth century figures from film, literature and classical music, which are apparently more respectable streams of culture. Mentions of Françoise Sagan, Günter Grass and Thomas Mann emerge in the discussion, as a device that seeks to give Lagerfeld (and the author) a sizeable dollop of cultural capital. In effect, the dialogue reflects the pervasive hegemonic conception of fashion, and one that hinders its progress as a site for critical discussion.

Historically, fashion has an uncomfortable relationship with critique: mainstream media coverage by newspapers and magazines often shy away from rigour and analysis on fashion’s output of events and collections. This is a dynamic that is constantly repeated in its discourse. References to other cultural disciplines, namely art and literature, are used to legitimise the domain of fashion, and suggest that it’s an industry that fails to measure up to a similar level of intellectual rigour.

Reinforcing this notion, in the article Lagerfeld is presented as a creative genius in the world of fashion: ‘our premier idea of what a brilliant designer can be’; and is unashamedly showered with praise by O’Hagan: ‘I don’t know if I’ve ever met anyone more fully native to their own conception of wonder.’ In a more literal metaphor of the designer later in the piece, he is compared to the twentieth century conductor Herbert von Karajana as he tweaks the accessories to a Chanel outfit for the presentation in South Korea, a movement that is described as similar to ‘conducting the violin section during a rehearsal of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.’

Though some of O’Hagan’s comments to Lagerfeld are deserved, the heavy-handed approach portrays the designer as having a symbolic status that distances him from the commercial messiness of the industry.

‘The Maddening and Brilliant Karl Lagerfeld’ reinforces a convenient and problematic summary of fashion as a frivolous domain. Though T Magazine may not be the context for academic discussion on fashion, there is surely room for a bit more rigour when dealing with the subject matter. This may also reflect the dilemma facing all national newspapers and their glossy weekend supplements, which lend themselves as platforms for corralling (often luxury) ads, perhaps as a source of revenue to commissioning more serious news-style articles elsewhere. With that said, the history of The New York Times as a platform that offers more critical positions on fashion and dress – having featured writers like Ann Hollander, Cathy Horyn, Lynn Yaeger, among others – should set a stronger precedence for coverage such as this. Unfortunately, this article is yet another exemplar of the lack of critique in the discourse, a paradigm that means that fashion is constantly playing catch up on itself.

Laura Gardner is Vestoj’s former Online Editor and a writer in Melbourne.