1.

On December 8, 1952, less than a year after her television series debuted to audiences in the United States on the CBS channel, the eponymous star of I Love Lucy opened the tenth episode of the show’s second season complaining of feeling a little ‘blah.’ Standing by the mantelpiece in her front room, Lucy (played by actress Lucille Ball) told her friend and neighbour Ethel that she was off to the doctor to figure out her unexplained fatigue, weight gain, and general malaise. Clever Ethel’s expression shifted almost immediately from concern to elation, and after a beat she exclaimed: ‘Lucy, you’re going to have a baby!’

Lucy’s mid-century cultural context did not welcome the adjective that properly described her state and as such, the script was carefully calibrated, both on and off screen. The word ‘pregnant’ was considered so indecent that the episode was instead titled ‘Lucy Is Enceinte,’ purloining from the French to make the situation sound infinitely more genteel. Had audiences reached immediately for their Merriam-Websters, they would have found that Lucy’s condition was being summed up en français by a word that denoted ‘the enclosing wall of a fortified place,’ a perfect connection to that other public mother figure, Mary, and her virgin conception so often signified in early Christian visual art by a verdant, fecund walled garden.

TV audiences were mesmerised by the drama playing out on their screens. Ball, after all, was actually pregnant, and thus embodied the tension between a character circumscribed by domesticity and, simultaneously, a mother-to-be working (as an actress, no less) outside the home. While the stereotype of a housewife’s homelife was acted out, its public, popular nature troubled traditional notions of propriety which dictated that a burgeoning stomach was a literal sign of sex, an unflattering silhouette, and something more safely rested behind closed doors. The idea of having a pregnant actress portray a pregnant woman on television was considered so shocking that the show’s major sponsor, Phillip Morris, first suggested Lucy hide her changing body behind tables and chairs. (The company was yet to be aghast at the health implications of their cigarettes being consumed by pregnant people.) But Ball, Lucy’s on- and off-screen husband Desi Arnaz, and the show’s producers rejected that idea, transforming what could have been the end of the series into a new arena for television audiences. Using the very same lens as previous episodes – the day-to-day happenings of an all-American middle-class family – Lucy’s changing body, clothing, mood swings, cravings, and baby name choices made a formerly private experience a public one in front of an audience of forty-four million viewers, reflecting the particulars and power dynamics of family life amidst the emerging Baby Boom. And it was Lucy’s maternity clothing that, mining a childlike language of bows, tented tops, and Peter Pan collars, masked the unutterable, and made pregnancy socially palatable, cementing Lucille Ball’s capital, cache, and celebrity in the process.

2.

In his career-defining collection of ten essays published in 1974, Greedy Institutions: Patterns of Undivided Commitment, U.S. sociologist Lewis Coser defined the subjects of his text as organisations that ‘seek exclusive and undivided loyalty and … attempt to reduce the claims of competing roles and status positions on those they wish to encompass within their boundaries.’1 In essence, Coser’s research interrogated how human capital – in the form of emotional, physical, and spiritual labour, attention, and above all, personal allegiance – is marshalled, maintained, and instrumentalised within organisational structures. While Coser explored this idea of total loyalty within a wide range of social groupings – including sixteenth century Ottoman courts, nineteenth century utopian communities, and the Catholic Church – it was his wife, Rose Laub Coser, also a professor of sociology, who, in their co-authored chapter, applied this lens to the relationships between human capital and power within a far more pervasive social group: the ‘greedy institution’ of the family.

Laub Coser’s work pioneered a close reading of the constraints experienced within the family unit by individuals who self-identified or were socially identified as mothers. From her first edited volume, The Family: Its Structures and Functions (1974), through to the manuscript unfinished at her death two decades later, World of Our Mothers, Coser articulated the frictions of women caught between the expansiveness of the modern world and the ancient demands of fealty to family.2 Laub Coser’s analysis tracked the ensuing tensions between these identities that have in great part defined modern life of the last century in ways that intersect class, culture, and community. Following her logic, when women occupy statuses outside of a single institution (the home), even if – and especially if – they are ‘incompatible and contradictory’ with one another, the resulting ‘segmentation’ of their attention and time resists the ‘greed’ of the family.3 Her scholarship, contemporaneous with groups like the Boston Women’s Health Collective (who authored the groundbreaking Our Bodies, Ourselves in 1970) and the radical Black feminist Combahee River Collective (founded in 1974, and also Boston-based, as the Cosers were for a large part of their lives), challenged the oppression inherent to an unyielding social expectation of women’s singular loyalty to the domestic sphere.

3.

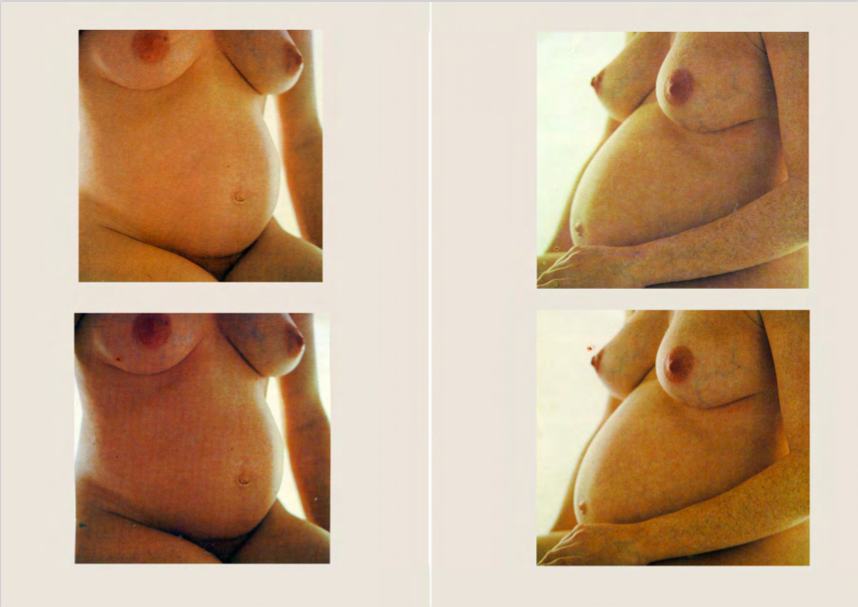

In the last few years, there has been a particular efflorescence of writing and visual arts practice centering on the stages of life that are sometimes collectively called motherhood, and that, knowingly or not, interrogate the power dynamic identified by Laub Coser. These include the photographers Carmen Winant, with her My Birth installation at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (2018), and Heji Shin’s 2017 Baby series currently on display as part of the Whitney Biennial, and writers Maggie Nelson (The Argonauts, 2015), and Sheila Heti (Motherhood, 2018). A particular standout is young Australian writer Jessica Friedmann, with her collection of autobiographical stories Things That Helped (2017), which describe the birth of her first child, Owen, during her mid-twenties, and her essay this year, ‘Motherhood Is a Political Category.’ In the latter, she invokes the term ‘matrescence,’ describing the psychological process of becoming a mother that she and her peers mine. Ostensibly things have progressed since Lucy and Laub made their transgressions. And yet, Friedmann writes, it is still true that:

Motherhood is a political category … we are told it is something we must cherish and excel at. Motherhood is janitorial work. It is health care. It is elder care. It is care for the environment, rapidly choking under industrialisation. It is working against the carceral system as it rips families apart … It is an exquisite pleasure and a wonder and a privilege. It is also, by every metric, just a fucking raw deal.4

Conjuring the work of anthropologist Dana Raphael and psychologist Aurélie Athan, Friedmann also writes of the need to construct an identity separate from her child. In one passage from her postpartum diary, this is achieved at the very threshold of preparing to deliver her son, dressed in the uniform of Cesarean section – blue hairnet, hospital gown, divested of all her own clothes, jewellery, and nail polish. She asks the attending nurse if she can retain her shock of red lipstick: ‘”I don’t see why not,” she says, laughing at me a little … I don’t laugh … My lips stand out like flames on an otherwise pale face – the last visible sign of any choices I have made on my own behalf.’5

4.

Maternity and fashion have long been uneasy bedfellows. It wasn’t until the early twentieth century that maternity clothing was even available for purchase within the commercial fashion system. During ‘confinement,’ as the Victorians termed pregnancy – as opposed to ‘temporary disability,’ as the U.S. working world terms it today – women were expected to conceal their growing abdomens within their homes and, if they left the house at all (as so many working class women did), inside maternity corsets. At the turn of the twentieth century, New York-based seamstress Lena Himmelstein Bryant Malsin cannily recognised that the shape and size of women’s bodies fluctuate, pregnant or not, and accordingly marketed adjustable garments under her company banner, Lane Bryant. Her female customers came in all stripes. Some were pregnant, and others were not, but all wanted a dress that would fit their body size (which for all of us, is always subject to change). Because Malsin designed dresses that could accommodate shifting biologies and silhouettes, the history of maternity wear was irrevocably linked with non-sample size fashion (marketed by Lane Bryant as ‘stoutwear’). The company also offered maternity wear by mail-order catalogue, modelled there and in other advertisements by chaste waifs whose slim bodies remained within the bounds of good taste and aspiration. As Malsin discovered, there was power and currency in fashion for pregnant women. Even while it masked the biological inevitability of greater ties to the home, a good maternity dress was a woman’s ticket to the external world, enabling her to more easily run errands, visit with friends, or continue to work and earn money with minimum public opprobrium.

5.

As the twentieth century progressed, many in the U.S. followed in Lena Bryant’s wake, including the Dallas, Texas-based label Page Boy. In 1937, using one of her sister’s suits as a prototype, engineer and (along with her sisters Edna and Louise) Page Boy co-founder Elsie Frankfurt cut out a window in the front of a skirt and implemented a horizontal loop and drawstring to make for an adjustable maternity garment called the Tie-Waist Skirt. The Skirt’s clever construction caught on, and it quickly became the ‘it’ mid-century maternity item, worn by the likes of Lucy, Grace Kelly, and the modern American mother-next-door. The Frankfurt sisters cannily sited the first of the Page Boy stores next to obstetrician’s offices, intertwining their brand with the midcentury imperative of babymaking and buying things. Page Boy’s advertisements seemed to suggest that pregnancy itself was a kind of metamorphosis that, if dressed properly for, could wall-in the more out-of-control and future-oriented anxieties contained within pregnancy, trading all that was unruly and ugly for something more tasteful and stylish. Their clothes promised a ‘pretty pregnancy,’ with fashions for ‘smart, young mothers to be.’

Though pregnancy remained a ‘condition’ for mid-century Americans, the Baby Boom meant the sheer number of expectant women made pregnancy more visible. By 1954, the year after Lucy introduced Ricky Ricardo Junior to television audiences, there were well over four million U.S. births annually, and the demand for fashionable maternity wear grew concurrently. A front page New York Times article from 1956 called maternity wear a ‘big business,’ citing that prospective families spent upwards of $200 million a year on it: ‘Today the expectant mother seeks to be as well dressed as she was before she was expectant … [and] desirous of looking her best at a most important time of her life, is more liberal in spending money for her wardrobe.’6 Instead of disguising the body, midcentury pregnancy now had its own language of fashion. It was about outward appearances, for sure, but it was also about the creation of an internal status quo through dressing pregnancy up as another event or life stage – cocktail party guest, prom queen, bride, expert cook – for which women could buy a costume and play the part. Per Friedmann, writing in the next century, little has changed: ‘It is no wonder that motherhood is so pressingly marketed as feminine. It’s the feminisation of any work that allows us to pay lip service to its importance and then ignore its material conditions completely.’7

6.

The midcentury maternity clothing boom predicted in the 1950s and 60s foreshadowed a market that would expand and diversify in the 1970s and 80s to accommodate popular demands for women’s rights to define a professional and personal life outside family structures. In the U.S. – and in other countries – policy began to evolve, including the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978. In the four decades since, its aftereffects have become resonantly codified in the rallying cry to ‘have it all’: to work outside of the home and experience motherhood, to have gender equity and celebrate biological reproductive specificity.8 To have choice, agency, multiple loyalties. The most ubiquitous design governing U.S. motherhood today (aside from lack of family leave and zero universal healthcare) has its history in this struggle. Not a garment but an accessory, the breast pump surged in sales after the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, which mandated coverage of lactation services (a mere seventeen years before, state laws had yet to be passed to protect the right to breastfeed in public). Lauded as a product that helps lactating people move with freedom while still being able to breastfeed their offspring, it is also a design that follows neatly in the path of the gadgets the I Love Lucy generation were sold for their home: washing machines, kitchen blenders, hair dryers. These ‘time-saving’ devices maximised productivity so women could do double (or triple) duty while making it look effortless. Little wonder the breast pump is operated out of sight, behind a locked door, hiding the labour involved – an output not yet matched by the thinking that has gone into designing the machine itself. New Yorker writer Jessica Winter has pointed out the ‘surprising and incalculable’ lack of investment in design products for pregnant people, and the amount of money Silicon Valley ‘kingmakers are leaving on the table by shunning women and mothers and babies. Breast pumps make up seven-hundred-million-dollar market, with ample room to grow.’9

7.

While fashion for working outside the home governs one branch of maternity wear, the late twentieth century bore witness to a second phenomenon that has come to shape cultural perception of pregnancy indelibly: the mass circulation of images of expectant celebrities (presaging reality television’s focus the intimate lives of others, and in many cases their home lives or reproductive capacities). One early – and perhaps still the most universal and global – example is Princess Diana of Wales who, in the early 1980s, utilised high fashion in the form of Bellville Sassoon coats, John Boyd hats, and Catherine Walker dresses as a strategic shield not only for her belly but also for her infamous shyness. On the flipside is the inimitable singer Grace Jones, whose maternity clothing was created in 1979 by her partner Jean-Paul Goude and Puerto Rican fashion designer Antonio Lopez. The most iconic of these ensembles, later to become the poster for the V&A’s 2011 exhibition, Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, was worn by Jones to her baby shower, held at 4am in a New York Night Club. Just like Lucy, both women used what they wore to mask their states – Jones because clubs wouldn’t book her otherwise, and Di because 1980s audiences were not yet ready to concede that even princesses had sex.

It took Demi Moore and Annie Leibovitz to truly break the mold in 1991. Their cover for Vanity Fair showed the actress eight months pregnant and naked save for a diamond earring and thirty-carat ring on a hand cupping her breast. There was no maternity fashion, per se (unless a ‘hand bra’ counts, which it doesn’t). The unclothed pregnant body was the story, and the scant, expensive accessories carried the day. Former Esquire art director George Lois called the cover an ‘instant culture buster,’ and he was right. In her 2008 autobiography, Leibovitz recalled the seismic waves her photograph created in terms of public moral offense: sold in a paper wrapper in some newsstands and refused at others, ‘as if it were a porn magazine.’ While pregnant women did not walk the streets naked as a consequence, maternity wear became less about cloaking the stomach and ‘the picture was held responsible for the rise of body-hugging maternity fashions.’10 Barely two years later, in 1993, the Family and Medical Leave Act was passed in the U.S. by President Bill Clinton. This act protected women’s jobs during pregnancy. In and out of the workplace, pregnant women traded smocks and tents for clothing that, for the first time, clung to the silhouette of the pregnant belly.

8.

The market for maternity wear has always been difficult to monetise because it has – like so much design for women across sectors – failed to attract venture capitalists or investors. Many brands are only available online, and most are reluctant to invest in these size ranges as they suspect shoppers won’t spend much on clothes they will only wear for a short period of time. Even as fashion choices widen, dedicated maternity retailers like Destination Maternity have seen their profit margins tumble over the last decade, and fast-fashion brands like ASOS and H&M dominate the market.11 In the new millenium, cheap garments already designed for deliberate obsolescence have allowed a cross-section of pregnant women to simply buy a few sizes larger as their bodies change through the trimesters, and then discard after use.12 This explains in part why no contemporary high fashion houses produce maternity wear, even as they relish the inherent drama of the maternal form and send pregnant models down their catwalks.13 Hatch is a rare outlier. Founded by former Wall Streeter Ariane Goldman, hers is an upscale maternity wear company that has grown every year since its debut in 2010. Its focus is not simply clothing, but a concept store and an Instagram lifestyle that creates community through interviews with doulas, lactation experts, and – gasp – pregnant people themselves. At Hatch, the millennial generation can formulate a loyalty to self – through self-care and self-identity – as the foundation for family, work, or whatever comes next, moving the needle ‘from a two-dimensional, direct-to-consumer brand to a three-dimensional, meaningful destination where women can feel heard.’14

9.

On a sweltering Atlanta day in the summer of 2018, and with little more than a week to go before her due date, hip-hop’s breakout rap star Belcalis Marlenis Almánzar, aka Cardi B, broadcast her baby shower in real time over Instagram Stories. A fan of fake lashes and slicked back hair was business as usual for the singer, but her blush-pink bodycon dress and strappy stilettos highlighted the gait of a woman in late pregnancy. Unlike Lucille Ball’s public pregnancy six decades earlier, Almánzar eschewed flounces, peplums, tented overshirts, and clever tailoring. Instead, her ensemble took the dictate of a Vogue article almost a century old – to wear couture during pregnancy as ‘miracles of concealment’ – and turned it on its head.

To trace Cardi B’s meteoric rise to fame is to follow her from tabloid pregnancy rumour to the Labour & Delivery ward (which she also filmed – as did Demi before her). Her story has myriad precedents in the realm of music and entertainment, including Beyoncé Knowles-Carter’s internet-shattering 2017 pregnancy announcement (then the most ‘liked’ Instagram photo of all time), and a wave of influencers who have used social media to announce each stage of their fertility journeys before and since. Being outside the home no longer requires veiling pregnancy – and indeed, for some, the home is no longer the ‘greedy institution’ but a space for money-making and entrepreneurship as Cribs, the Kardashians, and the entrenchment of reality TV sited in the domestic sphere attest.15

While these beacons of matrescene break the internet, they are simultaneously enclosed behind an enceinte wall of glossy, social-media fuelled images that disguise and distract attention from the socially-dictated mandates that leave pregnant people so vulnerable. No matter what they wear, embodied experiences of pregnancy in the U.S. do not follow suit. That tennis star Serena Williams can as easily almost die of childbirth related complications as any other Black mother in the U.S., yet draw more attention for her on-court catsuit, proves that money and fame are still no insulation from racism and biology. When a quarter of postpartum U.S. women return to work outside the home within ten days of giving birth, we know that whatever they wear will not protect them against retrograde and wholly inadequate family leave policy. When the most provocative reproduction-related garment of the last two years wasn’t one worn by a celebrity on the red-carpet, but a red cloak and white winged bonnet on the Netflix series, The Handmaid’s Tale, we know that the biological promise and threat of the ovary might be mediated in part through fashion, but the structures that demand loyalty, that enforce social greed, and that ultimately define motherhood cannot be recalibrated by simply dressing the part. As Friedmann notes, over centuries, and over almost every intersection imaginable, ‘the self may transform, but the system stays the same.’16

Michelle Millar Fisher is a curator of contemporary decorative arts at The Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Amber Winick is a design historian, curator and writer. ‘Designing Motherhood: A Century of Making (and Unmaking) Babies,’ is Michelle and Amber’s co-curated and first-of-its-kind cross-institutional endeavour on the subject of design for re-production, pregnancy, birth, and postpartum.

This article was originally published in Vestoj On Capital, available for purchase here.

L A. Coser, Greedy Institutions: Patterns of Undivided Commitment, New York: Free Press, p.4, 1974 ↩

L Coser & R Laub Coser, ‘Stay Home, “Little Sheba: On Placement, Displacement, and Social Change,’ Social Problems, Volume 22, Issue 4, 1 April 1975, pp 470–480 ↩

R Laub Coser, ‘The Complexity of Roles as a Seedbed of Individual Autonomy,’ in L A. Coser (ed.), The Idea of Social Structure: Papers in Honor of Robert K. Merton ↩

J Friedmann, ‘Motherhood Is a Political Category,’ in Human Parts, Medium.com, May 10, 2019 ↩

J Friedmann, Things That Helped: On Postpartum Depression, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p.29, 2017 ↩

G Fowler, ‘Baby Boom Helps Maternity Wear,’ The New York Times, January 22, 1956. ↩

J Friedmann, ‘Motherhood Is a Political Category,’ in Human Parts, Medium.com, May 10, 2019 ↩

Ironically, the phrase was coined by Cosmopolitan editor-in-chief Helen Gurley Brown in 1982, a figure who found human procreation so antithetical to getting ahead in work, intimate partnerships, and social circles that she mandated that her editors cover ‘no glums, no dour feminist anger and no motherhood.’ Helen Gurley Brown obituary, The Telegraph, August 14, 2012. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/9474548/Helen-Gurley-Brown.html ↩

J Winter, ‘Why Aren’t Mothers Worth Anything to Venture Capitalists?’ The New Yorker, September 25, 2017. https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/why-arent-mothers-worth-anything-to-venture-capitalists ↩

A Leibovitz, Annie Leibovitz At Work, New York: Random House, 2008 ↩

E Silverman, ‘Maternity clothes overlooked working moms-to-be. Retailers are looking to change that.’ Philly.com, February 9, 2019 https://www.philly.com/news/destination-maternity-clothes-pregnancy-working-moms-20190209.html ↩

The potency of Kate Middleton’s royal pregnancies in 2011, 2015, and 2018 has shaped this taste. They occurred during intense austerity in the United Kingdom and her fashion was scrutinized and praised by the British press, tabloid and broadsheets alike, who approved the wearing and re-wearing of high street brands like Jigsaw, ASOS, and Zara, as well as maternity-specific labels like Seraphine. ↩

Jourdan Dunn was an early pioneer for Jean Paul Gaultier’s spring/summer 2010 show, Eckhaus Latta sent a pregnant model down the catwalk for their S/S 2018 show and model Slick Woods even walked for Savage x Fenty while in labour in A/W 2018, going straight from the catwalk to the hospital to deliver. ↩

V Decker, ‘Ariane Goldman Redefines Maternity Fashion and Lifestyle with Hatch,’ Forbes.com, October 17, 2018. https://www.forbes.com/sites/viviennedecker/2018/10/17/ariane-goldman-redefines-maternity-fashion-and-lifestyle-with-hatch/#667fa8e3245f ↩

A decade before social media was endemic, in 2009, nine-months-pregnant musician MIA wrapped her polka-dot berobed performance with T.I. and Jay-Z on stage at the Grammy awards on her due date and, hours later, went into labour. Melanie Blatt, a member of the 90s alt-pop group All Saints, was a pioneer too, performing onstage in London in 1998 wearing a crop top that fully exposed her second trimester bump. She was in good company, with Victoria and Mel B of rival band, the Spice Girls, also expecting at the same time. ↩

J Friedmann, ‘Motherhood Is a Political Category,’ in Human Parts, Medium.com, May 10, 2019 ↩