TEXAS HATTERS IN LOCKHART, Texas, is located just off Highway 183 to Austin, and staffed by a fourth-generation of hat makers; starting with Marvin Sr., the Gammages have made hats for all from Willie Nelson to Hank Williams, Ronald Reagan and Prince Charles. Joella Gammage, her son Joel and husband David today ensure that Texas Hatters is full to the brim with cowboy hats in every colour and style, and that each customer is welcomed with banter, smiles and expertise in abundance.

***

Joel Aaron Gammage: My friend has a hat that is in between a top hat and a bowler. He wears that hat so much, people call him Country Slash. He’ll even wear it to the swimming pool! He’s an I.T. guy during the day, and a base player at night. I think the right hat has the tendency to bring out the inner character of a person. Your attitude changes. Cock your hat to the right a little, and all of a sudden you’re ready for a fist fight or a poker game. You know, guys don’t have as many facets of articles of clothing as women. You have your cowboy boots, belt buckle, and hat – whatever style.

There’s a historical side to the cowboy, the vaquero, which dates back to Mexican history. In its origin, hats were sombreros. We adapted them to a Western-European style. If we go back to traditional cowboys, your work was signalled by your hat. Depending on what your place was on the ranch, your brim was shorter or longer. It’s very similar to English culture. A tall hat was a symbol of stature.

In my grandfather’s day, hats were black or brown and that was it. There was only one way to wear a hat. My grandfather changed that. Today, hats are becoming more statement pieces. The functionality changed quite a lot. In the actual ranching community, it’s to protect yourself from the sun. But we wear it a lot still because it’s so ingrained. When you walk into a grocery store in a hat, you’ll grab people’s attention. You kind of just want to call that person ‘Sir,’ and treat them differently.

Joella Gammage Torres: I’m third generation. My dad and my grandfather worked together. My father proposed to my mother with a hat and a poem. It was a ladies high roller, with a telescoped crown, and the poem was something to the effect of: ‘Texas crown for the queen of my heart.’ How could she turn him down, right?

We’re in Lockhart, Texas. Prior to that we were in Buda, and before that we were in Austin. When we moved here, people who thought we went out of business thirty years ago in Austin found us because Highway 183 was their favourite road to take to Houston. There is a cattle auction down the road. When cattle prices are good… ‘Sold my cattle, I’ll buy a hat!’ But we get everyone: from what people call hipsters, to politicians and businessmen, fashionable ladies, everything.

The anatomy of a hat? First of all, the important lesson, would have to be that the crown is the part that sits on your head, and the brim is the part that sticks out. A lot of people get that reversed, which I don’t understand. Hats are made from straw or felt, or both. Leather hats exist, but we never made them. For the creases in the hat, there are some styles that can be done with a preformed block. We have quite a few of those, that are seventy-five to one-hundred-and-fifty years old. But primarily we soften the material and then we use our hands to do the creasing.

To make a hat, we have about a two-week waiting period, but if we had to walk one through, it takes a full day. Everything is by hand. We don’t start with something round on the top and flat on the brim and then put a crease in it. We make the hat from scratch, we do all the finishing and sewing here, we don’t use glue, all the ribbon trim is by hand. My dad said, quality is like buying oats. If you want good clean oats, you need to pay a fair price. If you want oats already run through the horse, that’s a little cheaper. We make every hat as though we make it for the most important person in our lives.

Our most popular hats hail all the way back to my dad’s time in the business. He made hats for Stevie Ray Vaughan, Ronnie Van Zant and Donnie Van Sant. There’s fans all around the world that want their hats just like them. The Ronnie Van Zant is similar to what I have on right now, only it’s a solid felt, with a rattlesnake belt on it. There’s a Stevie Ray Vaughan on that stand right there, with the ‘Do Not Touch’ sign. Both styles actually have an oval telescope crown. It’s creased inward and then comes back up, which is why we call it a telescope. And then the Stevie has a flat, bolero-type brim, and the Ronnie has the opposite: a pencil-rolled edge on the brim and then kinda rolled up cowboy-style.

The Gus hat is also very popular, it’s another one my dad created. If you’re familiar with Lonesome Dove, my dad created the styles for that mini-series. The Gus has a centre crease that runs from the front to the back, so it’s lower in the front, and two creases on either side of that so it looks like three fingers ran down the centre of the crown. It has curls on the side of the brim, as though you grabbed it with both hands. We call that a cowboy curl. The most iconic hat that came out before the Gus was probably the one James Dean wears in Giant.

Cowboy hat styles do evolve. Wider brims were really popular in the Forties, then in the Fifties they went a little bit shorter. I think part of it was people got cars. In the Seventies, all the crowns were really tall, like six inches, and really short brims. Today it is completely the opposite. Right now short crowns are really popular with a small dent, as if it fell off, and a really wide brim, barely curled on the side. Most of the colours are basic: black, silver buckle, straw coloured. But a lot of the guys and gals are going for brighter coloured brims now. They say, ‘I want you to notice that I have a style of my own.’ So they’ll put red, purple, or turquoise ribbons on the edges. As well as rhinestones now and then.

Each style also evolves according to who’s creasing it. There’s a design behind you called the horse shoe, it looks like a horse stepped on it. My grandfather would say that looks more like a mule shoe, because that’s how he did it. Everybody has their own hand. It’s like trying to copy some of the master painters, you can’t get the stroke exactly the same. [My husband] David has his style, I have mine. Often, when someone orders a hat from David or [my son] Joel, they have to be the ones that finish it up for them. And vice versa, the customer will recognise – that’s not how Joella did my last hat.

Joel is actually the most experimental. He went through this long phase of… particularly ladies that were interested in getting hats from him. And he’ll tell you, it drove me crazy! I like to think symmetrical, and everything he did was asymmetrical, kind of the Picasso of hat making. Technically they were still cowboy hats, but they were definitely a blend of Western fashion and high fashion.

Joel: In Austin you can pull anything off. You can walk down the street with butterfly wings, pink sunglasses and a miniskirt, and it would be fine. But if you would go to West Texas, and more traditional communities, you might get looked at a little funny. There’s still some traditional farmers and ranchers out there, but they are getting rarer, because you get a cultural shift where people want the modern standard that they see on TV, they want to live past the means they grew up with. For my family’s business, there was a need for somebody – after my grandfather died – to adapt to a variety of different cultures that come from the Austin community. You don’t notice it right now, but my accent will definitely change when I speak to other people. Before I got married, I went out dancing all the time, and I would wear a lot of hats, and sell a lot of hats. Now I do car shows and festivals and events and stuff. I was in the music scene already, so I wanted to bring that scene to Lockhart.

My personal favourite hat is a modified high-roller. If you’re familiar with the Ronnie Van Zant 38, it’s a telescoped crown, with a cylindrical shape and a curled brim. That’s one of the signature hats that I used to wear a lot. I called it my lucky hat. Whenever I wore it, people talked to me.

David A. Torres: I’ve seen wills being written up about hats. People come in here with their dad’s hat, which [my wife] Joella’s grandfather made, and they want it fitted to their size. Sometimes we’ll write down – made for so-and-so, passed on to so-and-so. In the twenty-nine years that I’ve been here, I’ve seen a hat pass on to the third generation once. Once I saved a family from not talking to each other, because two grandsons were fighting and both thought they had right to the hat. They didn’t want the money or the land, because the hat was a status symbol of an elder. They asked me to make another one just like it. I made an exact copy. I put them side by side, I knew which one was the original one, but then they got shuffled and I couldn’t tell which one was the real one. They both came and both offered money to me to let them know what the real hat was, but I honestly couldn’t tell them. They both have his hat over the mantelpiece.

Joella: There used to be drugstore cowboys, or urban cowboys. Someone who doesn’t actually work with cows, or on a farmer ranch, but dresses the part to attract women or men. Real cowboys looked down on them, but not so much now. We have a new generation of teenagers and twenty-somethings that do the rodeos. They raise their animals as children, and take them to shows. They’re real cowboys, but I’m always surprised when they come in here because they wear jeans other than Levi’s or Wranglers. They’re not wearing the traditional Western-style shirts. They’re wearing belts with fur and rhinestones, and headbands with rhinestones. But they’re not pretend, they’re the real thing, but their new style really surprises me. And they’re straight.

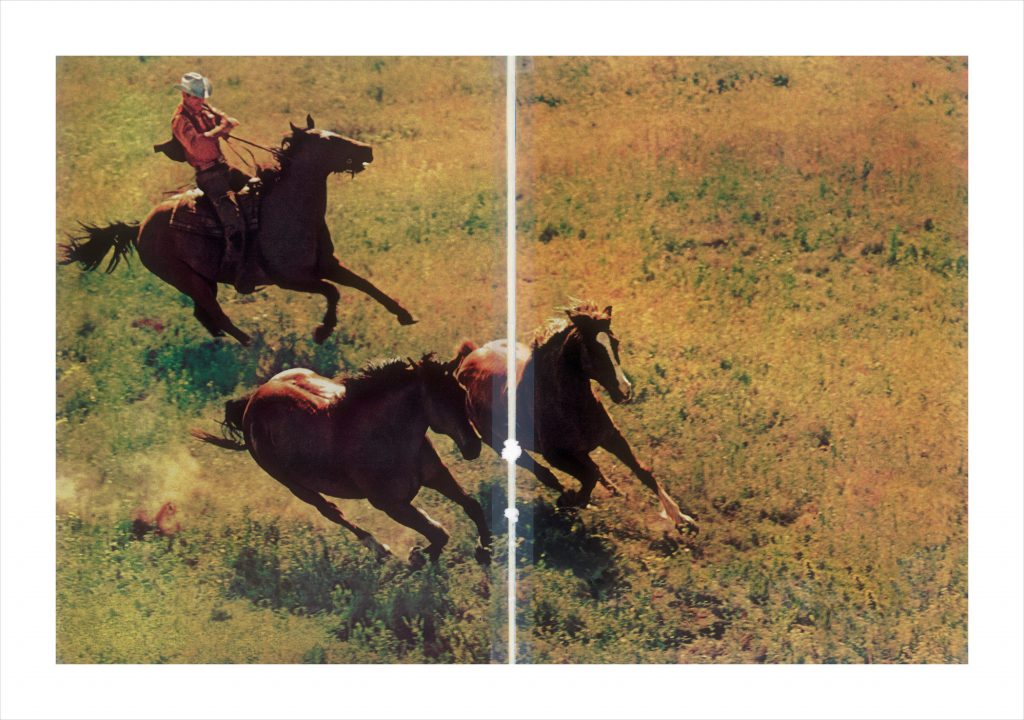

As a woman – not as a hatter – when I see a man in a cowboy hat, provided that he looks like a cowboy, not in shorts and flip-flops, I think: ‘That is a real man.’ I don’t know if it’s cultural, bred into us, but my mind goes to – he probably rides a horse, and deals with cattle, all those little-girl fantasies.

Joel: When I think about what a cowboy is, defining it in the traditional sense is almost impossible. There’s fewer and fewer ranches and farms. I’m one of the few people in my generation that actually decided to stay involved in my family’s business. And if you do manage to find a traditional cowboy, in certain communities, they might close their doors to you just because they’re afraid someone might want to come develop on their land. It’s gotten that serious; development has changed so much, there’s cotton fields and oil fields all over Lockhart, polluting all these areas. Places that have been cotton fields for a hundred years are now bought and sold for mass-housing production, so they’ll just become sub-divisions. And for whatever reasons, maybe that family needed the money, but it’s all changing everywhere.

To me, the definition of a cowboy is carrying on the heritage of, ‘When you say something you mean it. When something’s broke you fix it. When something ain’t broke you don’t mess with it. You preserve it.’ What a cowboy is to me, it’s maintaining integrity, and being able to stand behind what you say.

Anja Aronowsky Cronberg is Vestoj’s editor-in-chief and founder.