THE THIRD INSTALMENT OF a narrative interview conducted by Anja Aronowsky Cronberg for Vestoj ‘On Failure.’ Read the full chapter in the print edition here.

With:

Tim Blanks, editor-at-large at Business of Fashion

Thom Browne, founder & head of design at Thom Browne

Jean-Jacques Picart, fashion and luxury goods consultant

Glenn O’Brien, editor-at-large at Maxim

Steven Kolb, president & CEO at Council of Fashion Designers of America

Nicole Phelps, director at Vogue Runway

Nathalie Ours, partner at PR Consulting Paris

Robin Schulié, brand manager & buying director at Maria Luisa

Andy Spade, co-founder of Partners & Spade, co-founder of Kate Spade, founder of Jack Spade, founder of Sleepy Jones

***

Nathalie Ours: A garment should have a soul, a personality. That’s what distinguishes fashion from just clothes. But making fashion in big factories as we do today – where what matters is how much you can save on cost – you lose something. You lose the humanity. I’m not saying that this makes the product bad; it can still be desirable. I often see fashion shows and think a collection is amazing, but when I see it in the store I lose interest.

Nicole Phelps: Most consumers don’t want design innovation, exaggerated volume or a third sleeve on their garments. They want their garments to get them laid.

Andy Spade: Ultimately the consumer decides what works and what doesn’t. People in fashion like to criticise the big corporations who supposedly created ‘the system,’ but if the system were to break they’d all be without a job.

Steven Kolb: A fashion company has to worry about selling. That doesn’t mean that you can’t also strive to be creatively fulfilled, but being a fashion designer is being a businessman. Unless you make clothes as a hobby, you can’t use fashion as just a leisurely release of creativity – it’s very different from being an artist. To be a fashion designer is to participate in the fashion system.

Jean-Jacques Picart: In America fashion is an industry. Here in France we still find it hard to accept that fashion is commerce, and that beautiful things have to sell. Many designers suffer from a form of snobbery, where they think they should be above pedestrian concerns like how to sell a dress.

Robin Schulié: People talk about whether fashion is art or commerce, but that question is a false dichotomy. It’s both. The challenge if you’re a fashion designer is making a garment that has artistic value but that’s also commercially viable.

Thom Browne: The commercial side of fashion frustrates me. The way retailers buy collections, how conservative they are, how price conscious they can be, how they can just come into the showroom and say things they shouldn’t… I shouldn’t be so specific, but those are the little things that frustrate me.

Jean-Jacques Picart: The generation of designers that became established in the mid-Seventies knew how to bridge commerce and creativity. Kenzo Takada, Georges Rech, Sonia Rykiel. I call what they did ‘creative prêt-a-porter.’ There was an immediate connection to consumers. In 1976 I worked with Thierry Mugler and Kenzo Takada at the same time. Mugler would put on these spectacular and glamorous shows, and afterwards he would think of how to sell it. With Kenzo it was the other way around. He had his sales period before he showed the collection to the press, and we weren’t allowed to work on the show until the sales period had ended. The night before the show we would go through the collection. The sales people had organised two rails of clothing for us. One had all the clothes that had sold really well, and those we were obliged to show on the catwalk. And the other had clothes that hadn’t sold very well, so those we should show less of on the catwalk. Kenzo would come, look at both rails and start to mix the clothes that had sold well with those that hadn’t. He would mix a commercial flower pattern with, say, a more difficult graphic one to make both press and buyers happy. This is how the famous Kenzo mix-and-match style was born.

Robin Schulié: The retail landscape changed an awful lot in the late 1990s, when the big fashion conglomerates got involved. In the 1980s and early 1990s brands like Givenchy, Balenciaga and Louis Vuitton were still considered really stuffy and old-fashioned. Fashion-forward people bought clothes from new designers like Helmut Lang, Martin Margiela and Ann Demeulemeester – and they were sold in boutiques like Maria Luisa or L’Eclaireur here in Paris. When big corporations started investing in fashion, they realised that they had to get younger customers – the seventy-year-olds who were still buying Givenchy or Balenciaga were on their way out. So they started getting cool, young designers like Marc Jacobs or John Galliano to take over conservative old brands like Vuitton or Dior. These old brands had boutiques already, so to grow they started targeting department stores who were obviously interested because the big brands would hire floor space for ‘shop-in-shops.’ Department stores could make money the way a property developer would, with minimum risk involved. A department store structured in this way is like a mini-mall essentially. Independent stores like Maria Luisa have found it more and more difficult to compete, and many stores have gone out of business because of it.

Jean-Jacques Picart: In fashion we have to accept that there is an end to success. Every designer has a life cycle. An older designer retires, and a new one can flourish. This is the way it should be. That’s why I’m not keen on the revival of fashion houses. Why doesn’t a conglomerate invest in a new designer instead? An executive would say that an old brand already has a reputation, a ‘heritage,’ and that it will take less time to revive a brand like that than to build a new one from scratch. It’s a calculated risk, and succeeding in fashion is about taking calculated risks.

Tim Blanks: Death used to be so convenient for fashion; a brand stopped when the designer died. Now it’s like the walking dead; the whole notion of the zombie has had a pernicious effect on culture.

Thom Browne: A lot of people are afraid of taking risks because they’re afraid of failure. I’m not afraid of failure; I make sure that I don’t fail. At the beginning of my career in fashion, people certainly weren’t banging on my door to buy my collection. Not many people understood what I was trying to do. I remember thinking ‘What am I going to do if this doesn’t work out?’ And then I just thought, ‘I’m going to make it work.’

Andy Spade: My dad used to tape my pants up when I was a boy, and when I grew up I kept wearing my pants cuffed with coats from the boy’s department at Brooks Brothers. I used to work for Thom Browne, and he’d see the way I dressed and he started dressing the same. He’d turn up to the office wearing very short, cuffed pants. And then he took the idea and made a whole concept and a business from it. I was like, I should have thought of that! He beat me to it.

Jean-Jacques Picart: The generation of designers who are rising in the ranks today understand that they have to cater to the laws of commerce if they want to survive. They know that the era of John Galliano and Alexander McQueen is over.

Nathalie Ours: A designer who wants to stay in business has to take things very slowly, step by step. I’ve lost count of the designers who were the hottest ticket for a season; all the buyers wanted the clothes, and the designer got overwhelmed and couldn’t deliver on time. After two seasons like this the buyers get fed up because late deliveries mean that the clothes won’t spend enough time on the shop floor before the sales start. Or maybe a market blows up – as we had recently with the Russians. So many designers started getting orders from Russian boutiques, and then the market dropped. The designers never got paid. Young people think fashion is very glamorous, but really – it’s hard work. Fashion is glamorous for the two minutes it takes to take a bow at the end of a catwalk show.

Nicole Phelps: We’ve had few failures that can compare to John Galliano’s recent one. I guess the best way to describe it is as a private failure committed in public. People hypothesised that LVMH weren’t sorry to get rid of him. His business had been stagnant for a while and at least from an editorial point of view he had peaked a long time ago. And now he has taken on another very visible job at Margiela, and he’s back on the stage. He failed, but he’s managed to come back.

Tim Blanks: John Galliano was always a loose canon; he was always a miserable mean drama queen. I remember being with John in a London nightclub in 1989. He just got up from the table, pulled his cock out and pissed all over everybody. He could never handle his drink or drugs. McQueen was exactly the same, and on top of that severely unbalanced and heavily suicidal. He was always self-destructive. His experience as a child was so insanely traumatic that he could have been working in a road crew on a highway and it wouldn’t have made one bit of difference. You can’t blame the industry for the cracks in someone’s psyche.

Glenn O’Brien: What I see around me is only heartache and misery. Vanity. Enslavement of Third World people. People thinking that they are more important than they are. People without consciousness or principles. That’s the corporate world of fashion we have today.

Robin Schulié: The fashion industry today is a beautiful lie. Nobody is happy. Everyone is fucking frustrated. I don’t see happy faces – I don’t see happy people doing their jobs.

Nathalie Ours: In the 1980s fashion was still fun; there were no real rules yet. There were fewer brands so each designer occupied a much greater share of the market. Now there are so, so many brands.

Tim Blanks: As far as I’m concerned Cristóbal Balenciaga and Charles James are the two most fascinating people in the history of fashion. In fact, Charles James is a key person when you’re talking about success and failure. He was human and inhuman at the same time, such a genius. He was always pushing boundaries – never accepting the limits of his material. And at the same time he was a dyed-haired, drunken, queeny, vicious, bite-the-hand-that-feeds-you fuck-up. Like Caravaggio – biting his patron’s hand. I kind of like those people. John Galliano. He inherited Charles James’ mantle. Both were such utter successes and such devastating failures at the same time. McQueen is another one. A genius that destroyed his own genius. Sacrifices. With people like that it’s always a matter of when, not a matter of if.

Glenn O’Brien: People have always been attracted to success; it’s our natural instinct. We want to survive, move up and get rewards but those rewards are illusory. We find that out later, when it turns out we didn’t make it. We see the dream getting further and further away the more we chase it.

Nathalie Ours: Sometimes I wonder how long we can actually expect a designer to be successful when fashion is so fleeting.

Tim Blanks: I remember going to the Met to see the McQueen show; the queues were a mile long. There were people there who wouldn’t know McQueen from a bar of soap. There they were queuing up to see what this Icarus-like figure left behind. As if that would reassure them that they took the right course in their lives – that it really was better not to fly too close to the sun. That’s the price of genius – self-immolation.

Robin Schulié: We expect a lot from our designers today in order to think of them as successful. We expect them to have their own brand, while designing for a big house. We expect them to have shops worldwide. We expect them to constantly be in the press.

Tim Blanks: Someone like McQueen makes ordinary people fantasise: ‘What would it be like to be a staggering, glittering genius? What would it be like, to not be me?’

Robin Schulié: Look at young brands like Christopher Kane, Nicholas Kirkwood or J.W. Anderson. The corporations that own them are investing so much money in them, they aren’t allowed to just grow organically. The expectations are very high, and that in itself can be disastrous for a brand that is still establishing itself. These brands were profitable before they got investment from Kering or LVMH – they already had private backers. But they couldn’t afford to lose money so they couldn’t grow. When they get backing by corporations, their growth speeds up immensely all of a sudden. New shops are opened, new campaigns appear in the press. And now these companies that were previously profitable, start losing money. Their sales don’t match the investment they’ve received. The sheets aren’t balanced. It makes me wonder how long it’ll be before one of them hits the wall.

Tim Blanks: Cristóbal Balenciaga walked out of his office one day, turned around, locked the door and walked away forever. He closed his business when ready-to-wear started in 1968. A German company had the license to produce wedding dresses and perfumes, and they sold it to a French company in the mid-Eighties. In the early Nineties Josephus Thimister was placed as the head designer for ready-to-wear – Nicolas Ghesquière came later as a license designer. Thimister came from Antwerp and must have been brought on after the momentum that Tom Ford created at Gucci. Executives started thinking about another old venerable fashion label to resuscitate, and Balenciaga must have cost about a penny to buy. Thimister was just so fabulously wrong; he did a show with some Belgian New Beat band that played live so loud that by the third look the auditorium was a third empty. By the end of the show, the only person left – and this is one of my favourite fashion memories ever – was Suzy Menkes sitting in the middle of the front row, her hands covering her ears. When Ghesquière took over after that, there was really nowhere lower to go in the hierarchy – the next step would have been to get the receptionist on design duty.

Jean-Jacques Picart: A good collection is one that fulfils three key points. You have to present things that are already known, as well as others that are the same but with a slight twist. And then you have to present things that are completely new. Buyers never buy the thing that’s completely new – those serve as research for the following season. A designer also has to show that he understands the codes of the house: that we’re at Isabel Marant and not Haider Ackermann. The bulk of the show has to be recognisable looks but with new proportions, colours or a slightly different silhouette – that’s what will appeal to your buyers. And the completely new thing is what appeals to the press – it’s what we think of as risk-taking. And it’s what the buyers will order next season, when it already feels familiar. Few young designers understand this equation; they think that repeating themselves makes for bad design. They don’t understand that the focal point of their house is the product, and that the customer has to have a sense of familiarity.

Glenn O’Brien: Culture is getting stupider and stupider. I worked in the music industry for a long time. And what I learned was that a record company, Columbia Records for example, might have three hundred artists and they have to put the same amount of work – A&R, publicity, radio promotion – into each one. So when you come across a Michael Jackson and you make one hundred times more money than from all the other artists that still require the same work, the economies of scale dictate that you don’t want twenty really good artists, you just want one overwhelmingly popular one. Everything comes down to the bottom line.

This article was first published in Vestoj On Failure.

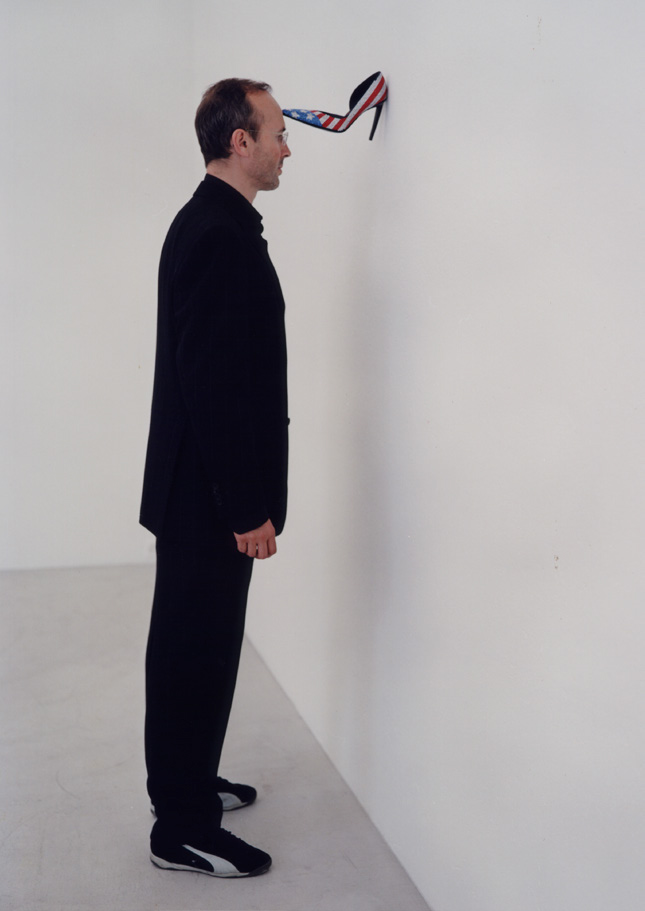

Erwin Wurm is an Austrian artist. These images are from his ‘One Minute Sculpture’ series, ongoing since the 1980s.

Anja Aronowsky Cronberg is Vestoj‘s Editor-in-Chief and Publisher.