In her book Victorian Babylon, Lynda Nead comes up with a striking metaphor for time, comparing it to a crumpled handkerchief.1 The metaphor suggests that time and history resemble a piece of crushed fabric. Elements of the past repeat in the present and future, the futuristic enfolds the archaic, and dramatic tears erase whole eras.

The idea of time as a crumpled handkerchief offers a welcome alternative to the notion of time as a linear trajectory that is moving in the direction of progress and continuous betterment. Perception of time as linear is one of the legacies of the Enlightenment era which saw history as moving away from ancient barbaric, uncivilised and primitive times towards perfection based on rational thinking and efficiency. Time, according to the ideals of Enlightenment, is not just linear, but also competitive – whereas some are closer to the perceived ideals, others are believed to be losing out, those are the people steeped in timelessness, unaffected by change.

This stereotype has, for centuries, served to justify the existence of colonial regimes the world over. In his seminal article Orientalism that preceded the publication of the eponymous tome, Edward Said writes about how the Orient has been Orientalised within the European literary and political discourses – precisely through its continuous relegation to timelessness:

Rather than listing all the figures of speech associated with the Orient – its strangeness, its exotic sensuosness, etc. – we can generalise about them as they were handed down through the Renaissance. They are all declarative and self-evident; the tense they employ is the timeless eternal; they convey an impression of repetition and strength; they are always symmetrical to, and yet opposed and inferior to, a European equivalent, which is sometimes specified, sometimes not.2

Said’s comment about the perceived timelessness of the Orient is adopted and expanded by Linda Nochlin in her essay The Imaginary Orient, where she discusses how Orientalist art and photography sought to visualise the absence of history and progress in non-Western spaces.3 Thus, The Snake Charmer by the French Orientalist painter Jean-Leon Gerome (used, by the way, as a cover image for the first edition of Said’s Orientalism) shows a crowd of mesmerised Orientals as they watch a naked adolescent snake charmer perform a risky show. The room is poorly lit, and the picturesque blue tiles on the wall are crumbling, as though to further convince the viewer in the ineptness and laziness of the Oriental folk. The scene is timeless, and time seems to be standing still.

According to Said, the Oriental timelessness is continuously portrayed as ‘opposed and inferior’ to the dynamic change in the West. This imagined difference has defined the position that non-Western knowledge and belief systems have occupied in the contexts defined and shaped by Western, post-Enlightenment values. The dichotomy between the West and the rest determines what has historically has been considered art or denounced as artisanship, what has been defined as fashion or dismissed as costume. The former, since the early days of fashion theory, has been defined by change and, hence, believed to be only possible in the changing and dynamic West. And all the East was believed to offer were the unchanging timeless ‘costumes’ and a rich repertoire of exotic styles and motifs for the West to borrow from. The colonial era culminated in a feast of cultural appropriation, from the Japonisme trend to the lavish cultural potpourri of the early-twentieth century designs, to the signature works by Saint Laurent, to the China-themed Met Gala: the list can go on.

Much to the dismay of critics of cultural appropriation and despite the many attempts to eliminate it, cultural borrowings, thefts and appropriations continue. As art historian Min-Ha T. Pham writes in her key piece for The Atlantic from 2014, the discourse on cultural appropriation is unproductive and futile.4 Cultural insensitivity occurs, is called out, apologised for, and buried in the annals of the Internet with little to nothing changed in our approach to or understanding of cultural appropriation.

The ongoing unproductive cultural appropriation discourse, argues Pham, only succeeds in solidifying stereotypes about the West as powerful and non-West as weak and open for plundering. As an alternative to it she suggests an inappropriate take on cultural appropriation. Looking at the history of the Indonesian plaid ornament, which continues to be appropriated and ‘elevated’ by Western designers season upon season, she encourages a more thoughtful and nuanced study of design history and design motifs. This can enrich and expand our understanding of non-Western fashion history, help recognise that fashion trends can originate in non-West, and, hopefully, promote more respect for non-Western fashion narratives.

Nead’s concept of history as a crumpled handkerchief might offer a good model for rethinking the hierarchies that still exist in culture and fashion. In my imagination, Nead’s crumpled kerchief is graced with a different ornament than the Indonesian plaid, albeit one with a similarly complex history. This ornament is a mutable motif, and at different times, in different places, it has been known as buta, Indian pine, cone, cucumber, or paisley – and it has also looked differently throughout the centuries. The Western reader would know it by the name of paisley, which evokes associations with contemporary luxury – fashion journalists have continuously referred to paisley as the signature ornament of the Italian house of Etro, and it sits with equal ease on an Hermes scarf, or a Ralph Lauren blouse.

And yet, however effortless and immediate the connection between the ornament and luxury fashion is, paisley’s history, once unfolded, presents a fascinating cloth, partially stained with violence and colonial prejudice. At different times, the ornament signalled affiliation with royalty and working class, evoked male elegance in India and ladylikeness in Europe, fashion and anti-fashion, mass production, artisanship and DIY chic.

The history of the ornament – or at least the history we have access to – dates back to Persia at the times of the Sassanid empire between the 3 – 7th centuries. The butoh pattern of the Sassanian times looked differently from the teardrop-shaped motif we know today, and the word butoh was used to mean a whole group of decorative floral and plant motifs used in architecture.5

In the 15th century, the butoh motif was gaining recognition in Northern India as a shawl pattern. The shawls were woven in Kashmir by – predominantly Muslim – weavers from the finest goat-hair fabric, sourced from the northern region of Ladakh. The word ‘shawl’ is derived from the Persian shaal and, in the 15th century, meant a fashionable mantle-like garment draped over the body.

The shawl production flourished under the patronage of the Mughals emperors, who ruled India from the 16th until the 19th century. The empire was established in 1526 by Zahiruddin Babur, a descendant of the legendary conqueror Tamerlan. The Mughal court replicated the organisation and aesthetics of the Persian court, Persia being the cultural trendsetter within the region at the time. One of the traditions the Mughals maintained was khilat, or gift-giving, through which the emperor would manifest his authority over vassals through presenting them with luxurious robes of honour. The Mughal khilat was a sumptuous set of clothes, which would consist of turbans, shawls, trousers, shirts, robes and scarves, all made from finest fabrics and embroidered with gold. The shawls, decorated with embroidered or printed floral motifs, were brought in fashion by the emperor Akbar in the 16th century and constituted the major detail in wardrobes of Mughal nobles. As the miniatures from the 16th and 17th centuries show, the shawls were styled as fitted to the body and were worn by men.

Patrons of art and culture, the Mughal emperors invested heavily into the development of shawl production as well as the patterns that graced them. As noted by Michelle Maskiell, the 17th and the 18th centuries saw the popularity of ornaments conceived specifically to please and honour the Mughal rulers ( the names ‘Shah Pasand’ (Emperor’s Delight), and ‘Buta Muhammad Shah’ (Muhammad Shah’s Flower) are telling).6

The buta ornaments constituted a whole wide category of floral motifs. The butoh-buta design was not static and timeless, but was influenced and shaped by the cultural processes happening in India and in the wider region. As John Seyller remarks, the 17th- and 18th-century Mughal art and design were impacted by the gardening culture and artistic exchange with Europe.7 At the Mughal court, cultivation of flowers and gardens was seen as a sign of culture, refinement and civilisation. Representations of the floral patterns on shawls celebrated and reflected the prestige of the court-approved art of gardening.

The design and production of shawls throughout the 16th and 17th centuries were highly competitive and dynamic. On a par with the Mughal-sponsored production of shawls in Kashmir, there existed other centres of shawl production across the region, like Kerman, where a different type of fleece was used for the production of shawls and similar floral designs were gracing them. The competitiveness between different artistic and design centres drove excellence and continuous improvements in the techniques of production and ornamentation, employed by the weavers. This dynamic competitive process starkly contrasts with the Orientalist image of the unchanging and timeless field of Indian artisanship, shaped by ancient traditions.

Europe encountered the Kashmiri buta-graced shawls by way of trade with Egypt, Ottoman Empire and Russia. By the middle of the 17th century, the shawls were known in Europe and, by the end of the 18th century, they were recognised as a stylish and highly valuable accessory for women. Then, at the beginning of the 19th century, the shawls, graced with the teardrop-like Indian-pine patterns were embraced in France, where Napoleon’s wife Josephine draped them over column-style, empire-waist gowns, as she is shown in Prud’hon’s portraits.8

Since the arrival of the shawls to Europe, they symbolised luxury and status – in Vilette by Charlotte Brontë, an Irish woman passes for ‘an English lady in reduced circumstances’ and is employed as a governess into a respectable household by virtue of owning ‘a real Indian shawl “un veritable Cachemire.”’ Costly and unique, the shawls were re-sold, inherited and sought after – London had a secondary market for the Kashmiri shawls, where high-society women in difficult circumstances could pawn theirs.

All the while, the British government sought to relocate the centre of production of the shawls to Britain, as the high import tariffs on imported luxury goods made the shawl trade senseless. After multiple and largely ineffective attempts to bring Kashmiri goats to Europe, the invention of the jacquard loom proved to be a game changer, leading to the foundation of British centres of shawl production – the most famous of them in the Scottish town of Paisley.

The designs from Paisley were of a lesser quality and much cheaper than the fine Kashmiri shawls, and the ornaments used to decorate them were imitations of the pinecone motifs, which, before getting renamed into paisley, were called, Suchita Choudhury points out, the Cashmere shawl design.9

The Scotland-produced shawls happened to become the epicentre of discourses around progress, modernity and class. On the one hand, the ornaments used for the Paisley shawls were decried as tasteless, incongruous and altogether inferior to the ones gracing the original Kashmiri shawls. On the other hand, they were celebrated as a testimony to progress that set Britain apart from the ‘unchanging’ East. Writing for the popular magazine Household Worlds, author Harriet Martineau argued:

If any article of dress could be immutable, it would be the shawl; designed for eternity in the unchanging East; copied from patterns which are the heirloom of a caste, and woven by fatalists, to be worn by adorers of the ancient garment, who resent the idea of the smallest change.10

The ‘Indian shawl design’ started to gradually go out of fashion in the second half of the 19th century and after the Mutiny in India – the 1857 uprising against the East India Company in India provoked a series of repudiations of the Indian designs, the most passionate one coming from John Ruskin, who denounced ‘the exquisitely fancied involutions’ of Indian design as signs of ‘lower than bestial degradation.’ From the end of the 19th century, the Paisley shawls and their curled ornaments would be relegated to working-class fashions.11

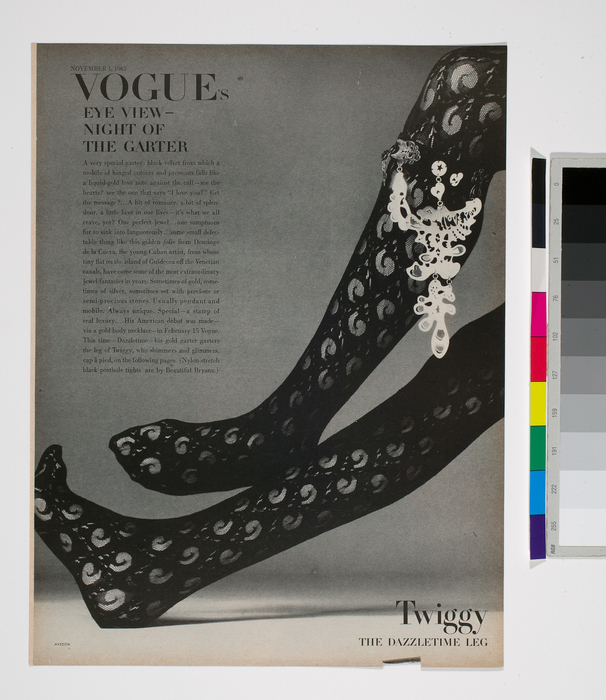

The next major resurfacing of the paisley ornament occurred throughout the 1960s – 70s during the hippie era and symbolised hippies’ attempt to radically divorce themselves from the disappointments of the Western culture. While the summer-of-love era decried racism and ushered in multiculturalism, it reiterated the old Orientalist dichotomies, portraying West as rational and modern and East as spiritual, timeless and mysterious.

Around the same time, a collection of old shawls and a trip to India kickstarted the history of Etro, celebrated for its ingenious interpretations of the paisley pattern and accused – every couple of seasons – for cultural appropriation. Yet, with Etro, the pinecone ornament is yet again firmly established in the vocabulary of global luxury fashion.

The story of the paisley ornament – or would it, in fact, be more accurate to call it the ‘Cashmere shawl ornament’? – is a testament to the non-linearity of history. Its shape and design have been formed by travel, trade, cultural exchange, imperial violence desire for distinction. It has been praised, criticised and forgotten, and at different times, it has channeled different meanings – through its associations with aristocracy and masculinity in India, femininity in the post-French revolution Europe, mass production and working class in the colonial-era Scotland. It is hard to say which of these meanings are truer, purer, or more important – all of them resulted from change in history and cultural exchange. The metaphor of a crumpled handkerchief allows us to admit the complex and illogical developments in history, letting us see fashion and culture in their rich randomness and to seek answers for the future of fashion beyond the great narratives.

Ira Solomatina is a researcher, lecturer and writer whose interest lies in the intersection of globalisation, gender and fashion.

L Nead, Victorian Babylon: People, Streets and Images in Nineteenth-Century London, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000 ↩

E Said, ‘Orientalism,’ The Georgia Review, Spring 1977, 31:1, pp. 162-206 ↩

L Nochlin, The Imaginary Orient, 1989 ↩

https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/05/cultural-appropriation-in-fashion-stop-talking-about-it/370826/ ↩

S Khazaeimask and S M Hejazi, ‘Plant designs in Sassanid Period mouldings,’ Bulletin de la Société Royale des Sciences de Liège, 2017, p. 696-710 ↩

M Maskiell, Consuming Kashmir: Shawls and Empires, 1500– 2000, Berg, 2009 ↩

J Seyller, A Mughal Code of Connoisseurship, Muqarnas, 2000, Vol 17, pp 177–202 ↩

C Zutshi, ‘“Designed for eternity”: Kashmiri Shawls, Empire, and Cultures of Production and Consumption in Mid-Victorian Britain,’ Journal of British Studies, 48: 2, 2009, pp. 420-440 ↩

https://www.vam.ac.uk/dundee/articles/a-tasteless-history-of-the-paisley-pattern ↩

C Zutshi, ‘“Designed for eternity”: Kashmiri Shawls, Empire, and Cultures of Production and Consumption in Mid-Victorian Britain,’ Journal of British Studies, 48: 2, 2009, pp. 420-440 ↩

https://www.vam.ac.uk/dundee/articles/a-long-way-from-home-the-paisley-pattern-and-india ↩