IN MILAN AND PARIS, she went from boutique to boutique, morning to night, like one possessed. They did no sightseeing at all. Instead of the Duomo or the Louvre, they saw Valentino, Missoni, Saint Laurent, Givenchy, Ferragamo, Armani, Cerutti, Gianfranco Ferré. Mesmerised, she swept up everything she could get her hands on, and he followed behind her, paying the bills. He almost worried that the raised digits on his credit card might wear down.

Her fever did not abate after they returned to Japan. She continued to buy new clothes nearly every day. The number of articles of clothing in her possession skyrocketed. To store them, Tony had several large armoires custom made. He also had a cabinet built for her shoes. Even so, there was not enough space for everything. In the end, he had an entire room redesigned as a walk-in closet. They had rooms to spare in their large house, and money was not a problem. Besides, she did such a marvellous job of wearing what she bought, and she looked so happy whenever she had new clothes, that Tony decided not to complain. Nobody’s perfect, he told himself. When the volume of her clothing became too great to fit into the special room, however, even Tony Takitani began to have some misgivings. Once, when she was out, he counted her dresses. He calculated that she could change outfits twice a day and still not repeat herself for almost two years.

She was so busy buying them that she had no time to wear them. He wondered if she might have a psychological problem. If so, he might need to apply the brakes to her habit at some point.

He took the plunge one night after dinner. ‘I wish you would consider cutting back a little on the way you buy clothes,’ he said. ‘It’s not a question of money. I’m not talking about that. I have no objection to your buying what you need, and it makes me happy to see you looking so pretty, but do you really need so many expensive dresses?’

His wife lowered her gaze and thought about this for a time. Then she looked at him and said, ‘You’re right, of course. I don’t need so many dresses. I know that. But, even though I know it, I can’t help myself. When I see a beautiful dress, I have to buy it. Whether I need it, or whether I have too many, is beside the point. I just can’t stop myself.’ She promised to try to hold back. ‘If I keep on going this way, the whole house is going to fill up with my clothes before too long.’

And so she locked herself inside for a week, and managed to stay away from clothing stores. This was a time of great suffering for her. She felt as if she were walking on the surface of a planet with little air. She spent every day in her room full of clothing, taking down one piece after another to gaze at it.

She would caress the material, inhale its fragrance, slip the clothes on, and look at herself in the mirror. But the more she looked the more she wanted something new. The desire for new clothing became unbearable. She simply couldn’t stand it.She did, however, love her husband deeply. And she respected him. She knew that he was right. She called one of her favourite boutiques and asked the proprietor if she might be allowed to return a coat and dress that she had bought ten days earlier but had never worn. ‘Certainly, Madam,’ she was told. She was one of the store’s best customers; they could do that much for her. She put the coat and dress in her blue Renault Cinque and drove to the fashionable Aoyama district. There she returned the clothes and received a credit. She hurried back to her car, trying not to look at anything else, then drove straight home. She had a certain feeling of lightness at having returned the clothes. Yes, she told herself, it was true: I did not need those things. I have enough coats and dresses to last the rest of my life. But, as she waited for a red light to change, the coat and dress were all she could think about. Colours, cut, and texture: she remembered them in vivid detail.

She could picture them as clearly as if they were in front of her. A film of sweat broke out on her forehead. With her forearms pressed against the steering wheel, she drew in a long, deep breath and closed her eyes. At the very moment that she opened them again, she saw the light change to green. Instinctively, she stepped down on the accelerator.

A large truck that was trying to make it across the intersection on a yellow light slammed into the side of her Renault at full speed. She never felt a thing.

Tony Takitani was left with a roomful of size-2 dresses and a hundred and twelve pairs of shoes. He had no idea what to do with them. He was not going to keep all his wife’s clothes for the rest of his life, so he called a dealer and agreed to sell the hats and accessories for the first price the man offered. Stockings and underthings he bunched together and burned in the garden incinerator. There were simply too many dresses and shoes to deal with, so he left them where they were. After the funeral, he shut himself in the walk-in closet, and spent the day staring at the rows of clothes.

Ten days later, Tony Takitani put an ad in the newspaper for a female assistant, dress size 2, height approximately five feet three, shoe size 6, good pay, favourable working conditions. Because the salary he quoted was abnormally high, thirteen women showed up at his studio in Minami-Aoyama to be interviewed. Five of them were obviously lying about their dress size.

From the remaining eight, he chose the one whose build was closest to his wife’s, a woman in her mid-twenties with an unremarkable face. She wore a plain white blouse and a tight blue skirt. Her clothes and shoes were neat and clean but worn.

Tony Takitani told the woman, ‘The work itself is not very difficult. You just come to the office every day from nine to five, answer the telephone, deliver illustrations, pick up materials for me, make copies – that sort of thing. There is only one condition attached. I’ve recently lost my wife, and I have a huge amount of her clothing at home. Most of what she left is new or almost new. I would like you to wear her things as a kind of uniform while you work here. I know this must sound strange to you but, believe me, I have no ulterior motive. It’s just to give me time to get used to the idea that my wife is gone. If you are nearby wearing her clothing, I’m pretty sure, it will finally come home to me that she is dead.’

Biting her lip, the young woman considered the proposal. It was, as he said, a strange request – so strange, in fact, that she could not fully comprehend it. She understood the part about his wife’s having died. And she understood the part about the wife’s having left behind a lot of clothing. But she could not quite grasp why she should have to work in the wife’s clothes. Normally, she would have had to assume that there was more to it than met the eye.

But, she thought, this man did not seem to be a bad person. You had only to listen to the way he talked to know that. Maybe the loss of his wife had done something to his mind, but he didn’t look like the type of man who would let that kind of thing cause him to harm another person. And, in any case, she needed work. She had been looking for a job for a very long time, her unemployment insurance was about to run out, and she would probably never find a job that paid as well as this one did.

‘I think I understand,’ she said. ‘And I think I can do what you are asking me to do. But, first, I wonder if you can show me the clothes I will have to wear. I had better check to see if they really are my size.’

‘Of course,’ Tony Takitani said, and he took the woman to his house and showed her the room. She had never seen so many dresses gathered together in a single place except in a department store. Each dress was obviously expensive and of high quality. The taste, too, was flawless. The sight was almost blinding. The woman could hardly catch her breath. Her heart started pounding. It felt like sexual arousal, she realised.

Tony Takitani left the woman alone in the room. She pulled herself together and tried on a few of the dresses. She tried on some shoes as well.

Everything fit as though it had been made for her. She looked at one dress after another. She ran her fingertips over the material and breathed in the fragrance. Hundreds of beautiful dresses were hanging there in rows. Before long, tears welled up in her eyes and began to pour out of her. There was no way she could hold them back. Her body swathed in a dress of the woman who had died, she stood utterly still, sobbing, struggling to keep the sound from escaping her throat. Soon Tony Takitani came to see how she was doing.

‘Why are you crying?’ he asked.

‘I don’t know,’ she said, shaking her head. ‘I’ve never seen so many beautiful dresses before. I think it must have upset me. I’m sorry.’ She dried her tears with a handkerchief.

‘If it’s all right with you, I’d like to have you start at the office tomorrow,’ Tony said in a businesslike manner. ‘Pick out a week’s worth of dresses and shoes and take them home with you.’

The woman devoted a lot of time to choosing six days’ worth of dresses. Then she chose shoes to match. She packed everything into a suitcase.

‘Take a coat, too,’ Tony Takitani said. ‘You don’t want to be cold.’

She chose a warm-looking grey cashmere coat. It was so light that it could have been made of feathers. She had never held such a lightweight coat in her life.

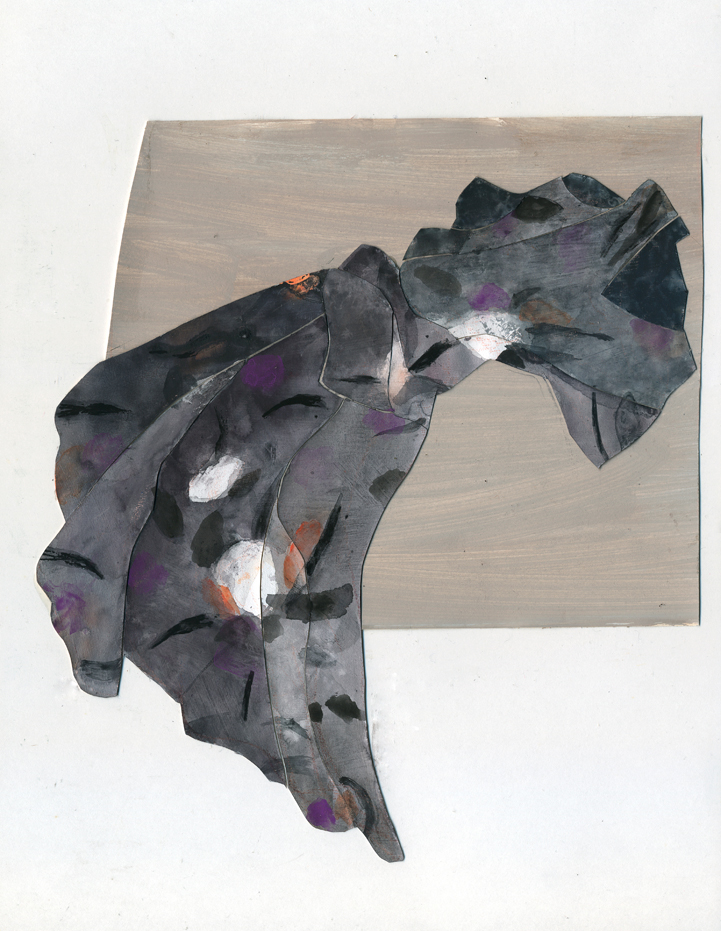

When the woman was gone, Tony Takitani went back into his wife’s closet, shut the door, and let his eyes wander vacantly over her dresses. He could not understand why the woman had cried when she saw them. To him, they looked like shadows that his wife had left behind. Size-2 shadows of his wife hung there in long rows, layer upon layer, as if someone had gathered and hung up samples of the infinite possibilities (or at least the theoretically infinite possibilities) implied in the existence of a human being.

These dresses had once clung to his wife’s body, which had endowed them with the warm breath of life and made them move. Now, however, what hung before him were mere scruffy shadows, cut off from the roots of life and steadily withering away, devoid of any meaning whatsoever. Their rich colours danced in space like pollen rising from flowers, lodging in his eyes and ears and nostrils. The frills and buttons and lace and epaulets and pockets and belts sucked greedily at the room’s air, thinning it out until he could hardly breathe. Liberal numbers of mothballs gave off a smell that might as well have been the sound of a million tiny winged insects.

He hated these dresses now, it suddenly occurred to him. Slumping against the wall, he folded his arms and closed his eyes. Loneliness seeped into him once again, like a lukewarm broth. It’s all over now, he told himself. No matter what I do, it’s over.

He called the woman and told her to forget about the job. There was no longer any work for her to do, he said, apologising.

Yuki Kitazumi is an illustrator based in Tokyo.

‘Tony Takitani’ was originally published in The New Yorker on April 15, 2002.