Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

William Blake, The Tyger, 1794

*

The sexual act is in time what the tiger is in space

George Bataille, The Accursed Share, 1949

On New York’s Upper East Side, where Madison Avenue meets the mid-eighties, one can find a trove of athleisure and luxury activewear stores which provide the inhabitants of the area with the necessary uniform the zip code requires: running pants, yoga pants, body warmers and leg warmers, all in the latest gradient colours, graphic designs and high-tech micro-mesh, ultra-breathable fabrics imaginable. These highly sophisticated outfits for walking the dog, running in Central Park, having lunch or lounging at home testify to a shift in status and signification of sportswear: originally intended for exercise, these hi-tech iterations have become an all-round uniform for the wealthy, who like to feel comfortable all day and do not have to dress or change for work, now harnessing the contradictory elements of being active yet ‘at leisure.’ The high-powered social and financial status of these uptowners is hence sartorially mirrored by the sophisticated sportswear they dress themselves in, which ultimately reflect their status. Once known as ladies of leisure (or ladies who lunch) these women, though now often identifying with a profession (yoga teacher, interior designer, artist, model), they still all too commonly rely on a husband for their expenditure. When visiting the stores these women frequent, one is struck by the quiet demeanour of the shopkeepers and the general atmosphere of leisure: in the corner, a woman is trying on the new plum colour leggings, there a girl is perusing the T-shirts whilst chatting to her trainer on the phone, a young mom rocks her stroller back and forth in front of the puffer jackets. Behind the counter, staff is chatting to each other, they are plenty and do not hurry or rush to the customer; they are confident the customer will ask for what she wants, in time, and it seems like they in turn enjoy there being a crowd of people at the ready, but not ostensibly so. The atmosphere is the opposite to what one might find in similar stores downtown, where people (presumably) have things to do and work to go to, and where the shop assistants are few and far between, and where athletic garments are usually worn for some form of exercise. The surplus of time and money of the Upper East Side clientele is mirrored in the quiet and calm behaviour of the store personnel: it is a Veblen-esque type of conspicuous consumption which shows off the privilege of the leisure class: a dressing down of your high economic status, and squandering time just because you can. These leggings and sports bras in muted colours are markers of status and wealth, an opulent lifestyle expressed not through golden logos but mesh fabrics. The group habitus of these women shapes the bodies and local economics of the area, which is densely populated with plastic surgeons and athleisure stores, mirroring each other in the quest for physical perfection.

These dynamics of abundance operate on the principle of what French philosopher Georges Bataille called, ‘The Accursed Share’1 of the economy: the surplus, the luxurious, non-efficient part, an integral part of every society and especially under late-stage capitalism, when a large percentage of basic products such as food, garments and material good are wasted without being consumed. Technical innovation, he wrote in 1949, leads to more energy savings on the part of humans, but they also create dilapidation, a crisis of excess, and end up making life more complicated since, ‘if the system can no longer grow, or if the excess cannot be completely absorbed in its growth, it must necessarily be lost without profit; it must be spent, willingly or not, gloriously or catastrophically.’2 He then describes three ways different societies deal with excess energy: consumption, the non-reproductive sex act, and death, by means of war or human sacrifice. Bataille worked thirty years on his essay, and in a time of global over-production and -consumption, rapid technical innovation and a looming environmental crisis, his words shed new light on the notion of luxury and excess, which he sees as the driving forces of the economy. He even sees excess as a fundamental part of human identity, asserting mankind’s position at the top of the energy chain: ‘The general movement of exudation (of waste) of living matter impels him, and he cannot stop it; moreover, being at the summit, his sovereignty in the living world identifies him with this movement; it destines him, in a privileged way, to that glorious operation, to useless consumption.’3

In the first part of his essay, ‘Consumption,’ Bataille points towards the sun as the origin of the excess of energy that drives the earth’s operations, since most of the sun’s energy is ultimately wasted. For example, plants use solar energy to grow, but a herbivore eating those plants needs to consume more energy than the plant does in order to grow fat (another type of excess). The greatest example of this, in the animal world, is the tiger: that magnificent predator, whose existence ultimately depends on the massive amounts of molecular energy in space, and who needs the highest amount of energy and space ‘wasted’ in order to sustain himself. The tiger is the highest example of excess in the food chain: ‘In the general effervescence of life, the tiger is a point of extreme incandescence. And this incandescence did in fact burn first in the remote depths of the sky, in the sun’s consumption.’4 Similarly, he calls the sexual act a form of squandering excess, since more time is wasted in the sexual act than would be strictly needed, leading to his statement that ‘the sexual act is in time what the tiger is in space.’5 In terms of luxury, the Upper East Side clientele could be seen as the tigers (tigresses) of the fashion food chain.

On the other side of the spectrum of exuberance, we find a different form of excess, which links Bataille’s notions of sacrifice, sexuality and commodity consumption: the new generation of online, direct-to-consumer retailers such as PrettyLittleThing, Fashion Nova, Missguided and Boohoo who capitalise on the high demand for ever-changing and low-priced #ootds for young girls. These girls are both customers and consumers as well as peer-to-peer marketers of the brands (‘brand affiliates’ typically receive 6% of the profits earned through their traffic directed to the main platform). The outfits, ‘body-positive’ styles which are released at the staggering speed of seven hundred a week, are often pushed into the limelight by reality TV stars, Insta-influencers, bloggers and a mass of Youtubers and Instagrammers who are famous for their daily fashion and lifestyle content. On the brands’ websites, ‘Dresses from $10! ,’ ‘£8 and under!’ are some of the browsing categories, next to other interesting and identity-driven markers such as figure types (Curvalicious, Free the Leg, Sexy&Seductive, Petite), and style profiles (Girls Night Out, Boardin Jets, Vacay!, LittlePinkDress, GirlBoss). Most of the styles advertised by these sites are overtly sexy or unapologetically girly and easily recognisable. Young girls, from fourteen to twenty-five (with spikes up to thirty) from diverse backgrounds make up the largest share of these brands’ customers. Fashion Nova, one of the fastest growing platforms, is famous for its bodycon dresses and tight pants worn by curvalicious celebrities like Cardi B, Kylie Jenner, Blac Chyna, Amber Rose, Jordyn Woods (many of which are related, willingly or not, in some way to the Kardashian Klan). The body hugging and accentuating styles are reminiscent of Kim Kardashian West’s wardrobe staples designed by her husband’s label Yeezy and her show stopping archival outfits from 1980s favourites Thierry Mugler and Gianni Versace.

These platforms are currently accursed by the fashion world establishment and watchdog sites like Diet Prada who call out their supposed copycat behaviour (young as well as established design houses have led lawsuits against some of them). The brands are seen as examples of bad taste, akin to coyotes or vultures feeding off of other brands, and are sneered at by the fashion press, designers and high profile influencers (usually, the ‘Parisian’ type) alike. They are a form of ‘wear- once-and-chuck-in-the-bin’ excess, derided by the segment of the fashion establishment which prides itself on originality and quality, in- vestment wardrobe staples, and carefully planned editorial campaigns with blue chip models, stylists and photographers. Even though high fashion brands often use past creations as inspiration themselves, there seems to be a moral panic about this new type of design and customer. The new system of self-appointed celebrities, brand affiliates and influencers seems to have no gatekeepers, it it excessively democratic, its styles are ‘vulgar,’ derivative. What has the world come to when one can buy both access and influence while clad in $10 dresses?

It would seem like class distinction, rather than authenticity or originality, is the damning factor, since these brands cater to aspirational lower-middle class customers who, just like the upper tier, might like to squander their money and splurge on 80% off the whole website, even if starting prices are $28 rather than $280, or $2800. They are the great equaliser of the consumption drive at the heart of human endeavour, and the great equaliser of taste. The customers of these sites, usually from working class backgrounds, are the insurgents of the fashion economy, threatening the highest form of capital in the bourgeois fashion industry: good taste. According to sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s field logic,6 it is thus necessary for the fashion establishment to dissociate itself from these brands, as the lawsuits by designers and Kim Kardashian West alike against some of these brands prove. Bronx-based rapper and style icon Cardi B on the other hand, who produces collections in collaboration with Fashion Nova, has no such qualms, nor do Kylie and Kris Jenner, who publicly endorse the brand. Cardi B’s access to high luxury cars, yachts and watches and designer archives does not preclude her from boasting about a dress she got for $30: an interesting paradox which boosts the aspirational identification from young customers even more.

Ironically, Kim Kardashian, oft reviled by mainstream cultural media and serious fashion press because of her commodity fetishism and exhibitionism, puts herself in the position of the fashion establishment in a series of defensive tweets against the fast fashion brands who knock off the archival silhouettes she wears at the speed of light and tag her name in their posts: ‘It’s devastating to see these fashion companies rip off designs that have taken the blood, sweat and tears of true designers who have put their all into their own original ideas. I don’t have any relationships with these sites. I’m not leaking my looks to anyone, and I don’t support what these companies are doing.’7 Whether or not Kardashian West secretly collaborates with these fast fashion brands (like watchdog Diet Prada argues) while publicly chastising them, she certainly wants to distance herself from these ‘accursed’ brands, aspiring herself to be respected and seen as part of the establishment, as the holder of cultural and social capital, the tiger of luxury and ‘good taste.’ In a continuous play of tag, ‘You are it!’ ‘You are accursed!’ between these brands, the boundaries between high and fast fashion, between good and bad taste, and between the holders of cultural capital become increasingly blurred.

Apart from class distinction, another possible factor for these brands being ‘accursed’ by the fashion establishment might be their unapologetic sexual nature, their youthful and provocative styles which are perceived as the overt squandering of young human flesh at the altar of both sexual as well as material consumption. The out-there names of the bum-skimming, thigh-grazing and boob-squishing outfits available on these platforms do not lie: I got the drip; Bite the Bait; Taste my horchata; Everybody wanna be this miniskirt; She Bad. The shiny fabrics and pink tones recall the interior of the boudoir, if not softcore adult lingerie catalogues. It is a loud type of sexuality, which high fashion, even in its most provocative and sexual imagery, always seems to mute, by stylising and polishing the reality of human sexual functions through instrumentalising thin, usually white, sleek, Photoshopped bodies. The curvaceous, tan and overtly sexual, fertile female figure on display is vilified, seen as an outdated form of 1950s femininity which, in its new, coloured and working-class appearance, is threatening and castrating all at once. The body-positive celebrities with surgically altered, non- white bodies, are often ciphers for online abuse and criticism because of their use of exaggerated female stereotypes.

Whether the violent power dynamics of the contemporary fashion field are based on classist, racial or sexual anxieties, with different parties accu(r)sing each other of being a form of excess baggage, underneath these socio-economic and cultural motivations might lie a fundamental fear, the human fear of impending auto-destruction: ‘For if we do not have the force to destroy the surplus energy ourselves, it cannot be used, and, like an unbroken animal that cannot be trained, it is this energy that destroys us; it is we who pay the price of the inevitable explosion.’8

Karen Van Godtsenhoven is an Associate Curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, and works on the museums exhibition programming and collection development.

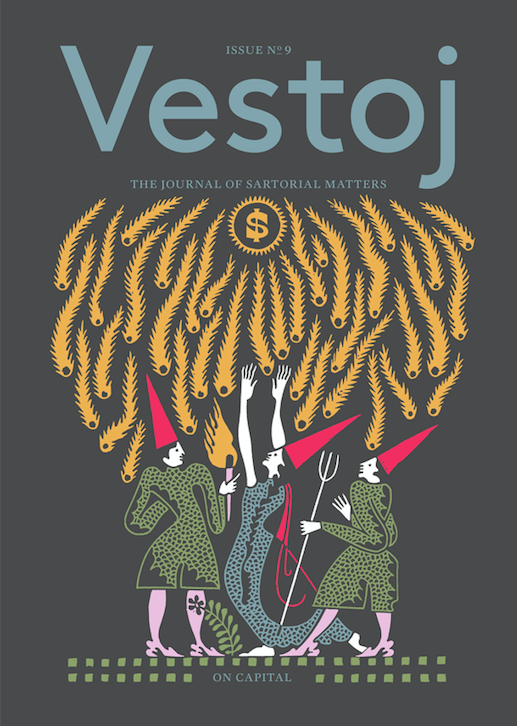

This article was originally published in Vestoj On Capital, available for purchase here.

G Bataille, The Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy, Vol. 1: Consumption, Zone Books, New York, London, 1988. ↩

Ibid., p.21. ↩

Ibid., p. 23. ↩

Ibid., p. 34. ↩

Ibid., p. 35. ↩

P Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, trans. R. Nice, Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1984 ↩

https://twitter.com/KimKardashian, on February 19, 2019 ↩

G Bataille, The Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy, Vol. 1: Consumption, Zone Books, New York, London, 1988. ↩