WHEN MAGUIRE BECAME PARLIAMENTARY-secretary to the Minister for Roads and Railways, his wife wound her arms around his neck, lifted herself on her toes, gazed into his eyes and said, adoringly,

‘Now, Paddy, I must have a fur coat.’

‘Of course, of course, my dear,’ Maguire cried, holding her out from him admiringly; for she was a handsome little woman still, in spite of the graying hair and the first hint of a stoop. ‘Get two fur coats! Switzers will give us any amount of tick from now on.’

Molly sat back into her chair with her fingers clasped between her knees and said, chidingly,

‘You think I’m extravagant!’

‘Indeed then I do not. We’ve had some thin times together and it’s about time we had a bit of comfort in our old age, I’d like to see my wife in a fur coat. I’d love to see my wife take a shine out of some of those straps in Grafton Street-painted Jades that never lifted a finger for God or man, not to as much as mention the word Ireland. By all means get a fur coat. Go down to Switzers tomorrow morning,’ he cried with all the innocence of a warm-hearted, inexperienced man,’ and order the best fur coat that money can buy.’

Molly Maguire looked at him with affection and irritation. The years had polished her hard-politics, revolution, husband in and out of prison, children reared with the help of relatives and Prisoners’ Dependents’ Fund. You could see the year on her fingertips, too pink, too coarse, and in her diamond-bright eyes.

‘Paddy, you big fool, do you know what you’d pay for a mink coat? Not to mention a sable? And not as much as to whisper the word broadtail?’

‘Say a hundred quid,’ said Paddy, manfully. ‘What’s a hundred quid? I’ll be handling millions of public money from now on I have to think big.’

She replied in her warm Limerick singsong; sedately and proudly as befitted a woman who had often, in her father’s country store, handled thousands of pound-notes.

‘Do you know, Paddy Maguire, what a really bang-up fur coat could cost you? It could cost you a thousand guineas, and more.’

‘One thousand guineas? For a coat? Sure, that’s a whole year’s salary.’

‘It is.’

Paddy drew into himself. ‘And,’ he said, in a cautious voice, ‘is that the kind of coat you had in mind?’

She laughed, satisfied at having taken him off perch.

‘Yerrah, not at all. I thought I might pick up a nice little coat for, maybe, thirty or forty, or at the outside, fifty quid. Would that be too much?’

‘Go down to Switzers in the morning and bring it home on your back.’

But, even there, she thought she detected a touch of bravo, as if he was still feeling himself a great fellow. She let it pass. She said she might have a look around. There was no hurry. She did not bring up the matter again for quite fifteen minutes again.

‘Paddy! About that fur coat. I sincerely hope you don’t think I’m being vulgar?

‘How could you be vulgar?’

‘Oh, sort of nouveau riche. I don’t want a fur coat for a show-off.’ She leaned forward eagerly. ‘Do you know the reason why I want a fur coat?’

‘To keep you warm. What else?’

‘Oh, well, that too, I suppose, yes,’ she agreed shortly, ‘But you must realize that from this on we’ll be getting asked out to parties and receptions and so forth. And – well – I haven’t a rag to wear!’

‘I see,’ Paddy agreed; but she knew that he did not see.

‘Look,’ she explained, ‘ what I want is something I can wear any old time. I don’t want a fur coat for grandeur.’ (This very scornfully.) ‘I want to be able to throw it on and go off and be as well-dressed as anybody. You see, you can wear any old thing under a fur coat.’

‘That sounds a good idea.’ He considered the matter as judiciously as if he were considering a memorandum for a projected by-pass. She leaned back, contented, with the air of a woman who has successfully laid her conscience to rest. Then he spoiled it all by asking, ‘But, tell me, what do all the women do who haven’t fur coats?’

‘They dress.’

‘Dress? Don’t ye all dress?’

‘Paddy, don’t be silly. They think of nothing else but dress. I have no time for dressing. I’m a busy housewife and, anyway, dressing costs a lot of money.’ (Here she caught a flicker in his eye which obviously meant that forty quid isn’t to be sniffed at either.) ‘ I mean they have costumes that cost twenty-five pounds. Half a dozen of ‘em. They spend a lot of time and thought over it. They live for it. If you were married to one of ‘em you’d soon know what it means to dress. The beauty of a fur coat is that you can just throw it on and you’re as good as the best of them.’

‘Well, that’s fine! Get the ould coat.’

He was evidently no longer enthusiastic. A fur coat, he had learned, is not a grand thing – it is just a useful thing. He drew his brief-case toward him. There was that pier down in Kerry to be looked at. ‘Mind you,’ he added, ‘it’d be nice and warm, too. Keep you from getting a cold.’

‘Oh, grand, yes, naturally, cosy, yes, all that, yes, yes!’

And she crashed out and banged the door after her and put the children to bed as if she were throwing sacks of turf into a cellar. When she came back he was poring over maps and specifications. She began to patch one of the boy’s pyjamas. After a while she held it up and looked at it in despair. She let it sink into her lap and looked at the pile of mending beside her.

‘I suppose when I’m dead and gone they’ll invent plastic pyjamas that you can wash with a dish-cloth and mend with a lump of glue.’

She looked into the heart of the turf-fire. A dozen… underwear for the whole house…

‘Paddy!’

‘Huh?’

‘The last thing that I want anybody to start thinking is that I, by any possible chance, could be getting grand notions.’

She watched him hopefully. He was lost in his plans.

‘I can assure you, Paddy, that I loathe – I simply loathe all this modern show-off.’

‘That’s right.’

‘Those wives that think they haven’t climbed the social ladder until they’ve got a fur coat!’

He grunted at the map of the pier.

‘Because I don’t care what you or anybody else says, Paddy, there is something vulgar about a fur coat. There’s no shape to them. Especially musquash. What I was thinking of was black Indian lamb. Of course, the real thing would be ocelot. But they’re much too dear, The real ones. And I wouldn’t be seen dead in an imitation ocelot.’

He glanced sideways from the table. ‘You seem to know a lot about fur.’ He learned back and smiled benevolently. ‘I never knew you were hankering all this time after a fur coat.’

‘Who said I’m hankering! I am not. What do you mean? Don’t be silly. I just want something decent to wear when we go out to a show, or to wear over a dance-frock, that’s all. What do you mean – hankering?’

‘Well, what’s wrong with that thing you have with the fur on the sleeves? The shiny thing with the what-do-you-call-‘ems – sequins is it?’

‘That! Do you mean that? For Heaven’s sake don’t be talking about what you don’t know anything about. I’ve had that for fourteen years. It’s like something me grandmother wore at her own funeral.’

He laughed. ‘You used to like it.’

‘Of course, I liked it when I got it. Honestly, Paddy Maguire, there are times when…’

‘Sorry, sorry, sorry. I was only trying to be helpful. How much is an ocelot?’

‘Eighty-five or ninety – at the least.’

‘Well, why not?’

‘Paddy, tell me honestly. Honestly, now! Do you seriously think that I could put eighty-five pounds on my back?’

With his pencil Maguire frugally drew a line on the map, reducing the pier by five yards, and wondered would the County surveyor let him get away with it.

‘Well, the question is will you be satisfied with the Indian lamb? What colour did you say it is? Black? That’s a very queer lamb.’

Irritably he rubbed out the line. The wretched thing would be too shallow at low water if he cut five yards off it.

‘It’s dyed. You could get it brown too,’’ she cried. ‘You could get all sorts of lamb. Broadtail is the fur of unborn Persian lambs.’

That woke him up: the good farmer stock in him was shocked.

‘Unborn lambs,’ he cried; ‘do you mean to say that they…’

‘Yes, isn’t it awful? Honest to Heaven, Paddy, anyone that’d wear broadtail ought to be put in prison. Paddy, I’ve made up my mind. I just couldn’t buy a fur coat. I just won’t buy it. That’s the end of it.’

She picked up the pyjamas again and looked at them with moist eyes. He turned to devote his full attention to her problem.

‘Molly, darling, I’m afraid I don’t understand what you’re after. I mean, do you or do you not want a fur coat? I mean, supposing you didn’t buy a fur coat, what else could you do?’

‘Just exactly what do you mean?’ – very coldly.

‘I mean, it isn’t apparently necessary that you should buy a fur coat. I mean, not if you don’t really want to. There must be some other way of dressing besides fur coats? If you have a scunner against fur coats, why not buy something else just as good? There’s hundreds of millions of other women in the world and they all haven’t fur coats.’

‘I’ve told you before that they dress! And I’ve no time to dress. I’ve explained all that to you.’

Maguire got up. He put his back to the fire, his hands behind him, a judicial room look on him. He addressed the room.

‘All the other women in the world can’t all have time to dress. There must be some way out of it. For example, next month there’ll be a garden party up at the President’s house. How many of all these women will be wearing fur coats?’ He addressed the armchair. ‘Has Mrs. de Valera time to dress?’ He turned and leaned over the turf-basket. ‘Has Mrs. General Mulcahy time to dress?’ There’s ways and means of doing everything.’ (He shot a quick glance at the map of the pier; you could always knock a couple of feet off the width of it.) ‘After all, you’ve told me yourself that you could purchase a black costume for twenty-five guineas. Is that or is that not a fact? Very well then,’ triumphantly, ‘why not buy a black costume for twenty-five guineas?’

‘Because, you big fathead, I’d have to have two shoes and a blouse and hat and gloves and a fur and a purse and everything to match it, and I’d spend far more in the heel of the hunt, and I haven’t time for that sort of thing and I’d have to have two or three costumes – Heaven above, I can’t appear day after day in the same old rig, can I?’

‘Good! Good! That’s settled. Now, the question is: shall we or shall we not purchase a fur coat? Now! What is to be said for a fur coat?’ He marked off the points on his fingers. ‘Number one. It is warm. Number two. It will keep you from getting cold. Number three…’

Molly jumped up, let a scream out of her and hurled the basket of mending at him.

‘Stop it! I told you I don’t want a fur coat! And you don’t want me to get a fur coat! You’re too mean, that’s what it is! And like all the Irish, you have the peasant streak in you. You’re all alike, every bloody wan of ye. Keep your rotten fur coat. I never wanted it…’

And she ran from the room sobbing with fury and disappointment.

‘Mean?’ gasped Maguire to himself. ‘To think that anybody could say that I…Mean!’

She burst open the door to sob.

‘I’ll go to the garden party in a mackintosh. And I hope that’ll satisfy you!’ and ran out again.

He sat miserably at his table, cold with anger. He murmured the hateful word over and over, and wondered could there be any truth in it. He added ten yards to the pier. He reduced the ten to five, and then, seeing what he had done, swept the whole thing off the table.

It took them three days to make it up. She had hit him below the belt and they both knew it. On the fourth morning she found a cheque for a hundred and fifty pounds on her dressing-table. For a moment her heart leaped. The next moment it died in her. She went down and put her arms about his neck and laid the cheque, torn in four, into his hand.

‘I’m sorry, Paddy,’ she begged, crying like a kid. ‘You’re not mean. You never were. It’s me that’s mean.’

‘You! Mean?’ he said, fondly holding her in his arms.

‘No, I’m not mean. It’s not that. I just haven’t the heart, Paddy. It was knocked out of me donkey’s years ago.’ He looked at her sadly. ‘You know what I’m trying to say?’

He nodded. But she saw that he didn’t. She was not sure that she knew herself. He took a deep, resolving breath, held her out from him by the shoulders, and looked her straight in the eyes. ‘Molly. Tell me the truth. You want this coat?’

‘I do. O, God, I do!’

‘Then go out and buy it.’

‘I couldn’t, Paddy, I just couldn’t.’

He looked at her for a long time. Then he asked.

‘Why?’

She looked straight at him, and shaking her head sadly, she said in a little sobbing voice,

‘I don’t know.’

Sean O’Faolain was an Irish writer best known for his short stories. ‘The Fur Coat’ was originally published in 1947, as part of O’Faolain’s collection, The Man Who Invented Sin.

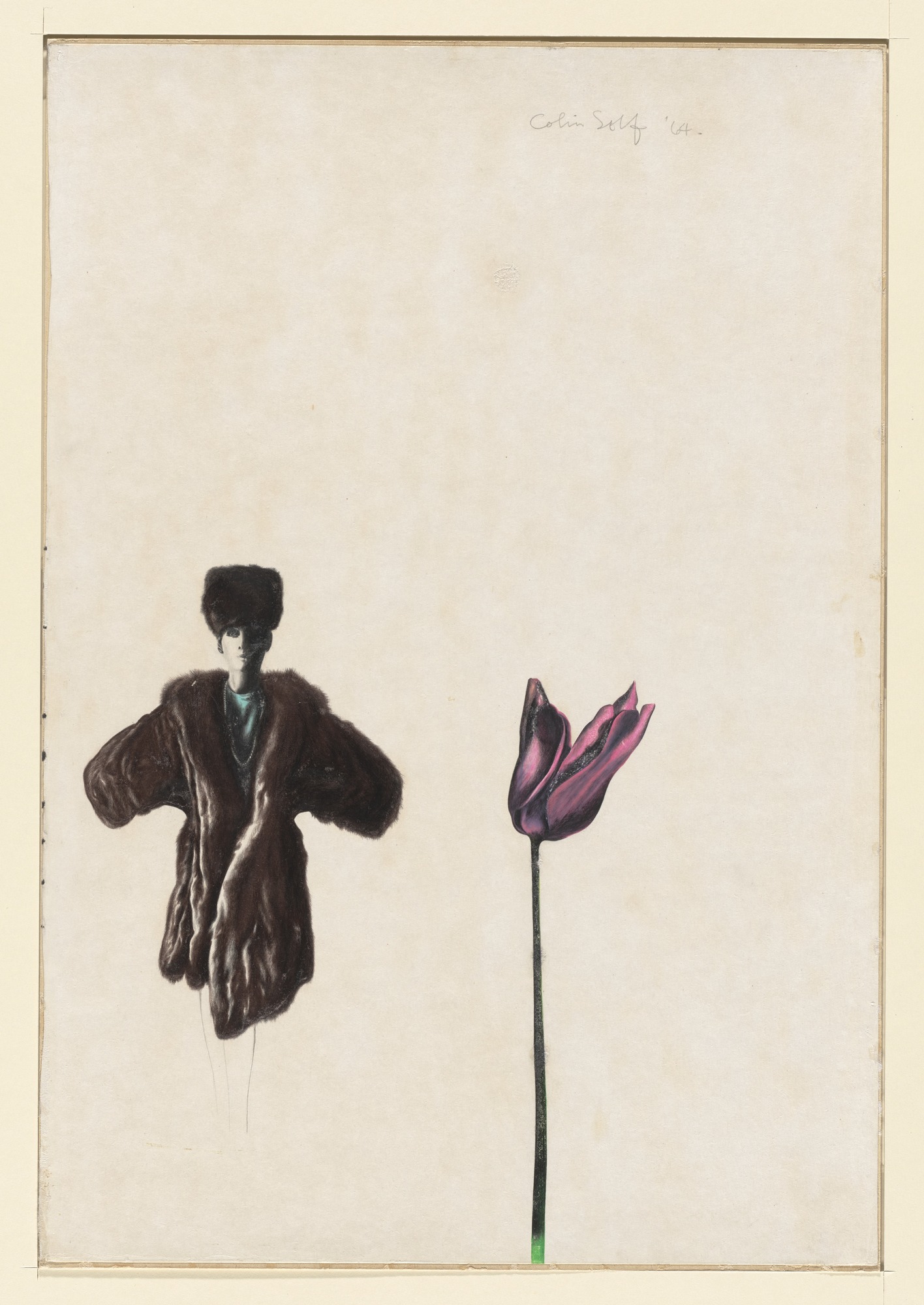

Image courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art (www.moma.org).