‘The hypnotic power exerted by things occult resembles totalitarian terror: in present-day processes the two are merged. The smiling of auguries is amplified to society’s sardonic laughter at itself; gloating over the direct material exploitation of souls.’

Theodor Adorno, Theses Against Occultism

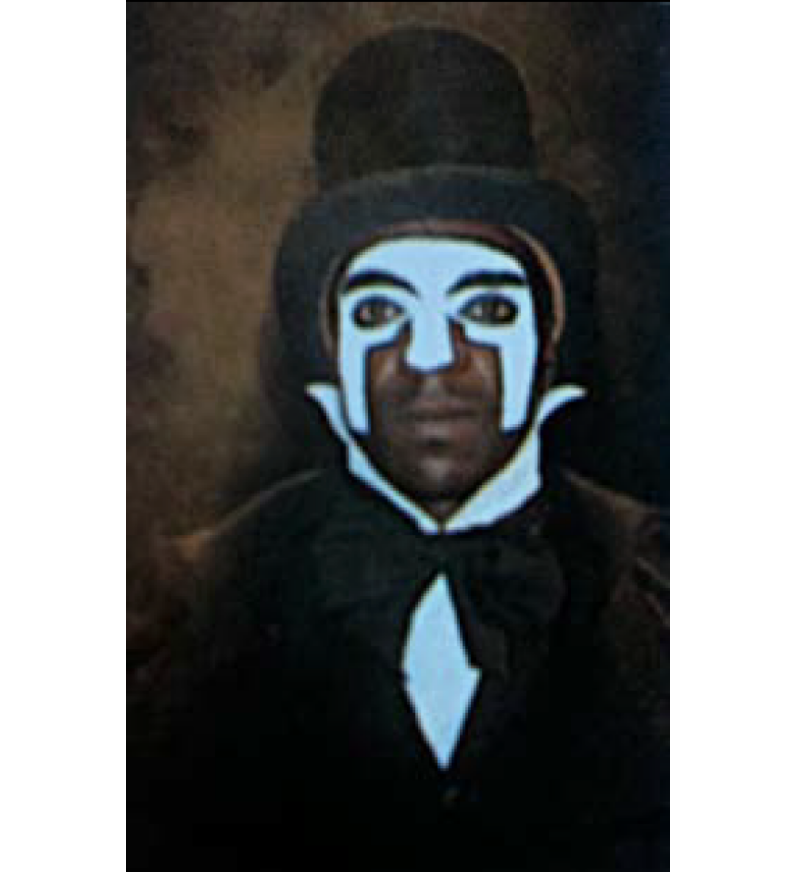

IN HIS 1946 THESES Against Occultism, Adorno addressed the swiftness with which occultism, when translated onto the political stage, could provide fertile ground for exploitation.1 Nowhere is this evidenced more theatrically than in the political intrigues of Haitian dictator François Duvalier, who from his election in 1957 to his death in 1971 harnessed and exploited the magical thinking of the Haitian people by dressing and acting like Baron Samedi, the voudou god of the dead. Duvalier used fashion to make implicit what he did not say explicitly: that he was a god, the god, of Haiti –and as such, was entitled not only to unmitigated power, but to absolution, loyalty, and even affection.

If Duvalier’s sartorial choices served to warn the people of Haiti that, like Baron Samedi, he controlled the border between life and death, they also had a secondary, more overtly political agenda couched in the Haitian ruler’s open advocacy for the religion of the Haitian majority: Duvalier legitimised voudou through his appropriation of the garments of one of its most precious deities. But, because much of the country’s budget was then underwritten by foreign aide, it was vital that, where a voudouist might see death incarnate, foreign administrations would simply see a man in a dark suit and glasses. His clothing, gestures and accoutrements served as a cipher, encoding to the Haitian people – to whom the significance of voudou iconography would have an immediate and visceral effect – but which would elude foreign observation.2

To unpack the political and sociological grounds for Duvalier’s psychological grip on the Haitian people, one must first understand the basic tenets of voudou, a religion that penetrates every facet of Haitian culture. Voudou dictates that below the surface of everyday life – which, for the Haitian, is a surface mottled with poverty and suffering – lies another, invisible realm, which runs parallel to our own but which is inhabited by voudou loa, or spirits. The role of the loa is a paternal and solicitous one: If respected and well nurtured, they provide protection and counsel, but can be fickle and quick to punish misdeeds. Loa are dependent on their living counterparts, requiring nourishment (literally, in the form of animal sacrifices) and attention (satisfied by voudou ceremonies led by houngan, or voudou priests).3

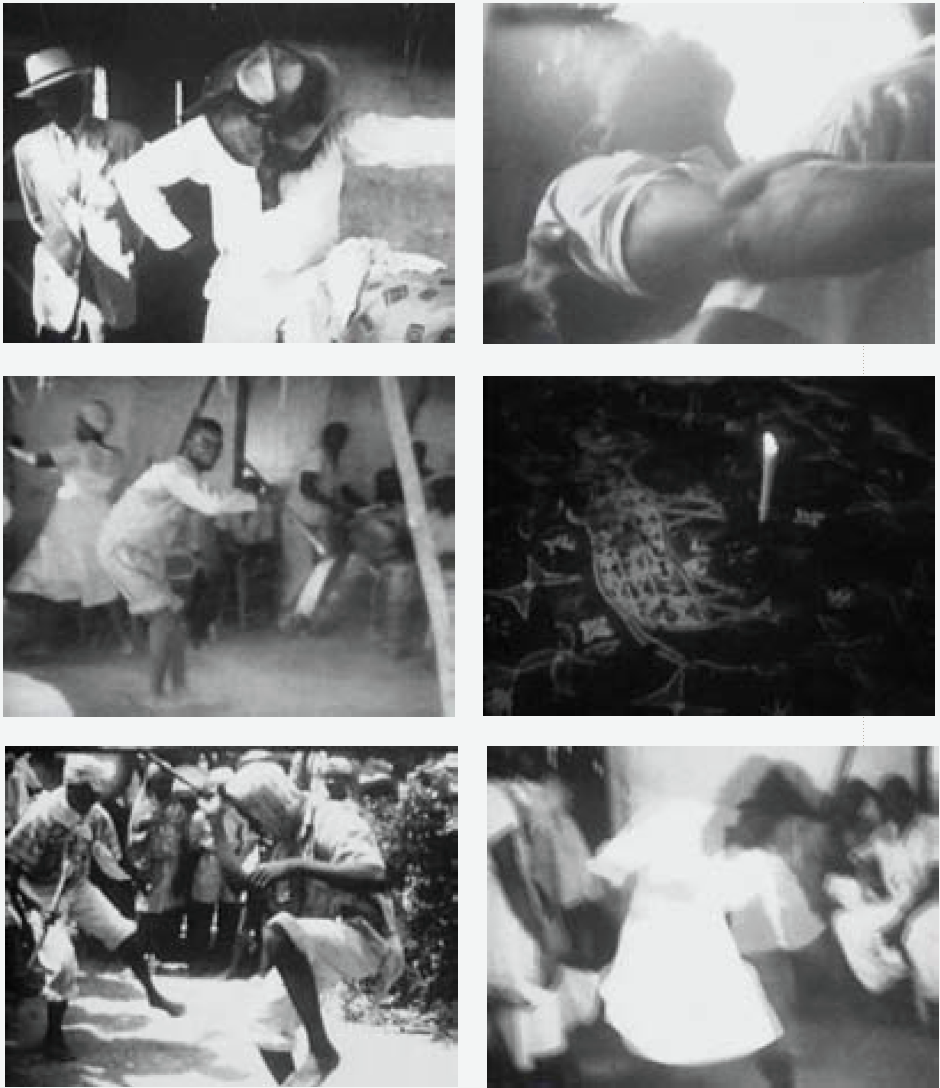

Entry to the spiritual realm is signified by the crossroads (represented figuratively as a cross within a circle, or a series of interlocking crosses), which figures symbolically into voudou ritual as the point of vertical axis between the physical and metaphysical planes. Crosses are drawn on the ground with flour, or traced in the air – around which participants in voudou ceremony writhe in a semi-circle, following a throbbing drum and rhythmic chanting.4 When a spirit manifests, it ‘mounts’ the body of the possessed person, like a rider on a feral horse. Images of possessed persons show them bucking, arms and legs akimbo and eyes rolled back, sometimes miming erotic behaviour, gyrating against trees or falling to the ground in a violent exhibition of mystical requisition.5

The goal of the voudou ceremony is to conjure these crossroads in order to make psychic contact with an otherwise unseen dimension. Of the voudou pantheon, deities closely associated with these points of contact are considered among the most powerful. Collectively called the gede, they are presided over by Baron Samedi, who – in alternating roles as healer, adviser and trickster – controls the portal between the living and the dead. Samedi is represented in voudou iconography as a corpse-like figure: white-painted or skull-like face, sunglasses (to protect eyes unaccustomed the brightness of the living), dark suit and top hat, and cane adorned with a phallus.6 Though certainly not the only ruler in history to strategically exploit costumery, his is among the most sinister – and, more importantly, the most self-conscious. Duvalier had studied the socio-cultural effects of voudou on the Haitian people and had co-authored essays on the subject.7

Voudou was the religion of the poor, black people of Haiti, and by becoming the first Haitian leader to publicly recognise voudou as a national religion, Duvalier legitimised the worldview of the common Haitian citizen. Though the majority of Haitian people were black, the mulatto class then controlled most of the wealth and was more closely aligned with foreign economic and religious power. Duvalier had campaigned on an anti-plutocratic, populist platform, eschewing foreign political and religious influence and representing himself as a simple country doctor to whom the humble, noirist values of the peasant class – voudou in particular – were sacrosanct.8

This had a binary effect on Haiti: on a spiritual level, Duvalier’s sartorial invocation of Baron Samedi conveyed his power over the lives and deaths of the Haitian population; his entitlement to respect and sacrifice; and his paternal role as provider and protector of Haiti. On a socio-political level, it communicated his backing of the populist, folk agenda and willingness to shepherd the neglected majority; to celebrate black culture; and to shelter Haiti from foreign powers who had done nothing – in the minds of the Haitian people – but exploit the island’s resources and repress its religion.

But Duvalier’s built persona took on such an outsized grandeur that the division between real and magical thinking in Haiti dissolved, and discourse surrounding his presidency – which was often seeded to the people by Duvalier himself – served not only to perpetuate his personal mythology, but to obscure the far more macabre realities of his reign. Rumours circulated in Port-au-Prince that Duvalier took baths wearing nothing but the top hat of Baron Samedi; that he stored a severed head in his chambers with which to commune with spirits of the dead, that he studied the entrails of a goat to predict his future and that his wife and daughter were trained mediums.9 It was said that he had journeyed to Trou Foban, a mountain cave outside Port-au-Prince, where he and a houngan lured spirits of evil back to the palace and trapped them in an otherwise empty room.10

In reality, Duvalier was responsible for tens of thousands of deaths and disappearances and used terror and torture as implements of personal redress. He kept a private torture room – painted rust-red to hide splattered blood – with holes drilled in the wall so that he could watch from the comfort of one of his adjoining chambers.11 His personal guard, the Corps des Volontaires de Sécurité Nacionale, would nightly replenish the stock of prisoners. Commonly known as the tonton makoutes – Creole for bogiemen or zombies – makoutes had previously been a fixture in voudou parables about misbehaved children, whom they were said to kidnap at night. Duvalier’s personal cache of makoutes was responsible for several thousand executions per month.12 Like their commander, their attire was tuned to ignite both nationalistic pride and sheer terror in the Haitian people.

Initially their symbolic zombification was limited to the dark sunglasses they wore at all hours to replicate images of the dark-eyed, nightprowling zombies in voudou mythology. Later, they took to wearing farm labourer’s dark denim, with wide-brimmed felt cowboy hats and red scarves in the style formerly worn by peasant guerilla caco fighters.13 These costumes mirrored the duality of coded information invoked by Duvalier’s Samedi wardrobe. With their sunglasses, they forged a visual link between themselves and the spirit world. But with their red scarves and denim, the makoutes aligned themselves with Haiti’s anti-colonialist revolutionary legacy; the cumulative effect was to position the makoutes outside and above the hegemonic order of political and social life. Duvalier, too, used the clothing and accoutrements of voudou iconography to mitigate the social backlash against his grab for power, and to align himself – however hypocritically – with the Haitian people. In effecting the persona of Samedi, Duvalier replaced himself as the axis between the two planes of existence – living and spirit – becoming, in the minds of his constituents, a living god.

Julie Cirelli is a New York-born, Copenhagen-based writer and the current editor of Kinfolk.

All images from ‘Divine Horsemen – The Living Gods of Haiti,’ (1985) filmed 1947-1954 by Maya Deren. Courtesy Microcinema International.

This article was originally published in Vestoj On Fashion and Magic.

T Adorno, ‘Theses Against Occultism,’ Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life, Verso, 1998, pp. 238-243. ↩

P C Johnson, ‘Secretism and the Apotheosis of Duvalier,’ Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 74 (2), 2006, pp. 420-445. ↩

M Deren, Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti, 60 minutes, Microcinema, 1985. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Ibid. ↩

C Boyce Davies (ed), Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora, Volume 1, ABC-CLIO, 2008, pp. 821. Over the course of his reign, Duvalier metamorphosed into Samedi in manner and mien, deliberately donning the voudou loa’s signature accoutrements – top hat and long, black coat, thick glasses and gold-handled cane – and effecting Samedi’s slow movements and high-pitched nasal intonation. ((B Diederich & A Burt, Papa Doc: The Truth About Haiti Today, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1969, p. 354. ↩

Ibid, pp. 47 ↩

P C Johnson, ‘Secretism and the Apotheosis of Duvalier,’ Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 74 (2), 2006, pp. 420-445. ↩

B Diederich & A Burt, Papa Doc: The Truth About Haiti Today, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1969, p. 355. ↩

E Abbott, Haiti: the Duvaliers and Their Legacy, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1991, pp. 82. ↩

Ibid, pp. 133. ↩

R F Wagner Jr, ‘The Duvalier Regime,’ The Harvard Crimson, June 3, 1963. ↩

E Abbott, Haiti: the Duvaliers and Their Legacy, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1991, p. 86. ↩