- THE BODY, IN THEORY

ABSTRACT

The price on stripper shoes has dropped precipitously. From the display on the mirrored wall, I pick up an open-toed shoe in red satin, with a dainty ankle strap, a three-inch clear plastic platform sole, and a five-inch stiletto heel: $45. Insanely cheap. I take my own shoe off, put on this one, jack my pant leg up to my knee, and turn around to see if the shoe creates a nice wavy line from ankle to ass, which it does,

(as much as it can, really, considering; the shoe does its best with a body this age and at this point in the slow reverse-simian process by which we devolve from upright to hunchbacked to all fours to the belly-down slither back into the grave, where our rapid deconstruction from the complexities of self to the simplest sort of cell begins, proceeds, and ends with a maggot, a memory, a quark)—

which is to say that, as far as the shoes can make my ass look good, they do.

And they’re only forty-five bucks! Which I swear to Christ is half what the same shoes would have cost ten years ago — these ridiculous, anti-ambulatory shoes, which are worn in one industry only, but in that industry are universally worn, more stilt than shoe, unwearable outside the club or off the set — these are not your day-to-evening-wear shoes, ladies! These are special shoes, the shoes of fantasy and fetish. Watch this! I slip my foot into the red shoe: my clothes fly off! My face erases itself like an etch-a-sketch! These are the ruby slippers, the glass slippers, the magic shoes; they fit only Cinderella, Dorothy, and Barbie’s plastic arched tiptoeing foot. They are photo-op ready, a perfect fit for any form of theory and critique. They are Chinese foot binding and a corset and liposuction and a nose job all at once. They are a chastity belt, a push-up bra, a ball gag and a babydoll negligee. They are original sin, the fall of man, the failure of feminism, the fault of feminists, non-feminists, anti-feminists, post-feminists, deconstructionists and poststructuralists. They are the errors of Barthes and de Bouvier, they are beauty myth and backlash, they are postmodernist jabberwock nonsense. They are a blight on humanity, evidence of social decay, death of the nuclear family, loss of family values, they are not shoes! Duchamp! Tell us: when is a shoe not a shoe? When it is a picture of a shoe. Right! When it is not a shoe but a sign. When it is a signifier worn by a sign. Then riddle me this: when is a woman not really a woman, but merely a sign?

When she is wearing these shoes. These are stripper shoes. These are the shoes of shame.

But actually I like them, and I am going to buy them. Christmas is ten days away; the stripper store where I am picking through the racks is full of red. There are Santa velveteen bikinis with white fur trim, red and black lace Merry Widows, there are red satin boy-shorts with black Santa buckles, which could be worn with red-sequined pasties with red satin swag that, if you are both large-breasted and talented enough, you can make swing in tandem, or even in opposite directions at once—

NB: I am neither large-breasted nor talented enough—

so I skip the pasties, but take into the dressing room with me the boy shorts with black Santa belt, and the Santa bikini with white fur trim.

I close the door. I turn my back to the mirror. I unbutton, unzip, and strip.

NOTES ON THE FASHION/ED BODY

- We experience our physical forms as ornamental items we wear, not as bodies we are. And as Nietzsche would have it, ‘Body I am entirely, and nothing else’ — the mind being an organ; the self finding its source in the brain; the body inseparable from the self, except insofar as we separate the two in the copula, in perception and language: they are not separable in fact.

But we do not say we are a body; we say we have a body. It is one of the things in our possession; one of the basic items in any woman’s closet, the little black dress, the well-fitting jeans, the white oxford, the suit of flesh and face. The body is subject to fashionable taste or distaste; to approval or disapproval, as may be the case, depending on how closely it adheres to the sartorial demands of the time.

The body as object is like any owned thing, in that it is intended to bespeak something about the owner. This creates radical dissociation of body from self, and perpetuates a fallacy of physical perfectibility, which in turn is intended to create the illusion of a perfect self. We see these body-objects we own, generally, as failures; they do not adhere to the fashion; and in this grand-scale Cartesian mind/body split, we create a psychic abyss in which festers shame.

- At the intersection of fashion and shame are bone-deep beliefs about sexuality, the body as sexual object, and the woman as sexual creature, which lie at the heart of a culture, and cannot seem to be killed off. The fantasised, fetishised nature of (especially, but not only) the female body perpetuates a culturally and historically specific varietal of shame, a doubled shame: for one’s failure to be object-perfect, object d’art, fashionably-bodied; and for having a body that is seen as a sexual object, not as fashion object or object d’art. The body-object is made up of fetishised parts that are alternately glorified and vilified, according to a visual and psychic vocabulary that compulsively reiterates the images of those parts. The body is broken down by our witness and internalisation of these images, until it is experienced as more part than whole, and the parts more empty sign than signifying entity. The attempt to amend the internal dissonance this creates is to fetishise oneself.

Today’s fashionable, fetishised body is, variously, sculpted, starved, shaved, waxed, toned, tight; childish, boyish; or, on the other hand, hyper-sexualised, performatively sexual, the epitome of sexual desirability, its sexual signs on display; but even this latter fashion requires upkeep and maintenance and perfecting and adornment and ornament — requires a certain sort of sexual performance even in repose — is not simply a sexual body, with sexual parts. It is a suit of sexual clothes. There is a way to wear it. It, like any other item of clothing, can’t just be tossed on and worn around; one must carry it off.

- And so the body is a creature created, controlled, manipulated, subjected to dictates of fashion, whim, and will. The body is fashioned of pieces, is made; is both fashion object and fetish; and is experienced as dismembered, as monster, mannequin, as Venus di Milo, headless and armless, as di Chirico’s severed heads and hands. It is kept in the room in the basement of the museum where they keep the smashed and broken bits of former masterpieces, the room where things lacking aesthetic beauty and wholeness are kept.

Our sense of self is infiltrated, in some cases defined, by a sense of being a shattered, broken thing; this consciousness of our own brokenness deepens our sense of shame.

The shame of being in a dismembered body is the shame of being a disintegrated self: a self without centre, without content, without worth.

This is not shame for something, some faux pas, some sin, for something done or left undone, not even for the failures, faults, and flaws of the body; the shame is deeper, more amorphous, and pervades the entire experience of embodiment. The shame is this: not only does my body fail to conform to fashionable norms; it fails as a body as such. It is not a body at all. It is pieces of a body, each inscribed with separate instances of shame. I am trapped in this cobbled-together creature’s form, and the fact that I can neither correct nor escape it causes both panic and shame.

I am not that body.

I am nothing but that body.

I am a thing less than the sum of its parts.

I am a surface, a scrim, a skeleton decked out with Christmas lights, a structure wearing a skin stretched taut over the empty hollow of what would be self.

I am not the self I seem to be.

I am not who I am.

I am not.

FASHIONING A BODY

So I must construct a semblance of self, or at least a place where one would be kept. Generally this means there is need for a body, a visible structure; one must be at least perceptible to the naked eye. The body should be fashioned of parts, the parts should be perfect, should be in keeping with the fashion of the time, should be placed correctly, none out of place, none marred; none worn out or old or past its prime.

Fallacies under which we labour: that the parts are not really attached. That we can replace the parts at will. That all parts must be perfect; that the parts we have are inherently flawed. That their flaw is our failure. That the flaw of the part ruins the whole. That a deviation or scratch or mar in the object ruins the object’s beauty; for example: as with a diamond, or a dog. Each is examined for the perfection of its disparate parts; the whole is judged on the presence of perfection in each.

As nice as a diamond might be, looked at from afar, if it is imperfect, it loses its value. Same with a dog; good dog, maybe, but imperfect, and therefore without value. The valuable dog is one whose parts all meet the standard of perfection of the breed.

The valuable woman is one who, peered at under the jeweller’s glass, has no inclusions, no marks, no scars. She is the one whose parts are compared to the parts of the phantasmal perfect woman, and are found to match. She is as good as a made-up woman: all perfect parts.

The valuable woman is clear as a diamond, good as a very good dog.

BEAUTY V. BEAST

Q: How to distinguish between fashion and fetish, object of fantasy and object d’art? Between a thing of beauty and a thing of shame? Between a woman who wears, as fashion, the objects of fetish, and the one who wears them as costume, and takes them off? Does one cast a shadow of shame on the wearer, while the other does not? Does the shame lie in the willingness to participate fully in fantasy, to subject one’s identity to the projection of the fantasising eye? Is donning a fetish object an erasure of self? Is it shameful, or is it playful, or is it pathetic, or is it an aesthetic choice, selecting the fetish-body from the array of women we keep on hangers in our closet? Where does the aesthetic (beautiful) end and the fetishised (shameful) begin?

A: I don’t know.

But shame goes deep, is sensed as self, is sensed as innate. Beauty is experienced as superficial, separate, projected onto the screen of one’s body by the scanning eye. Shame lies coiled in the core, is the raw sore of self; beauty skims the surface, rests lightly on the tensile skin of the water. Beauty—as we experience it—is only our portrait, our pose.

Q: Where do the crosshairs of fashion and fetish meet? On the female body, I’m asking. To what extent do we freely choose our aesthetic, our fashion; and to what extent is it a compulsory performance of body as fetish? What is the precise, pinprick-sharp site of shame?

FASHIONING A FETISH

Actually, what’s funny — the valuable woman, one who can exchange the disclosure of her parts for cash (the I for the eye) — need not have parts that match the standard of perfection of the breed. She need only have fetishised features; it is the fetish that pays. Some of these are exaggerations of the breed’s features: the ballooning breasts especially, but also the big ol’ ass. Some are derivations of societal fashion: the boyish hips, the barely-there breasts. Long hair is the more common fetish, but short hair has its fans; defined muscles are a drawback or an asset, depending on the taste of the viewer; they do not mean the same thing in the fashion of fetish as they do in the fashion of society (in the strip club, they are invested with meaning about feminine sexual willingness, not about personal power or self-control). Long legs are popular, but the exaggeratedly long, toothpick-straight, biologically impossible leg of the Victoria’s Secret catalogue is not required; curved thighs, a certain softness, a more Gibson Girl look, legs that may actually occur in nature, are cash-worthy as well. Each ethnicity has its fans; each of those fetishised bodies, in turn, has a fetishised fashion, which usually consists of a hyper-realised fantasy of a culture’s traditional garb. A pretty face is critical, of course, and calls a higher price; but the face is not a fetish object in itself; it need only have the requisite parts: primarily, a mouth that can make an O.

The only absolute in the saleability or valuation of the fetish body, more important than ‘beauty,’ more significant than a given trait, is youth — but this is imperative. The individual parts can be flawed, varied, deviating from or exaggerating the fantasy of perfection. But the body and face marred by the passing of youth are worth nothing at all.

- THE BODY, IN PRACTICE

ABSTRACT

They were plain shoes, unremarkable had they been simply shoes, had you seen them on the feet of a woman walking to work, or down the hallway of the standard-issue office to her cubicle, where she might sit down, kick off these unremarkable shoes, rub her nyloned toes together in the dark under her desk, sit for the day doing her work.

They were that sort of shoe, what used to be called a ‘pump,’ about a 2.5 inch heel, maybe 3. They were, one could tell at a glance, uncomfortable because cheaply made, with no arch support. They were made of dull black leather, though probably the leather was not dull when they were purchased, but now that the shoes had been worn and worn, day after day, the leather (probably not actual leather) had lost its sheen and its shape, taken on instead the shape of the foot, and because the foot bends, the shoes were bent and creased as well.

Additionally, the shoes were scuffed, and showed the outline of the smallest toe where it had been pressing through the leather for who knows how many years.

The shoes, in short, were old.

The shoes were out of fashion. The shoes were a bore. The shoes, had they been worn by the woman settling into her chair in her fluorescent office cubicle, would have been of no note. Would have gone unnoticed and unremarked; they were unremarkable, not ugly so much as simply worn out, and therefore without value, had they been simply shoes on the foot of a woman wearing clothes.

But since she was naked, except for these shoes, they were noticed. They were not stripper shoes. They had no platform sole, no 5-inch heel, no ribbon, no strap, no bow. They were not a thigh-high pleather boot or a clear plastic mule with a spray of feathers in purple or pink on the toe. They did not cause the ass to bobble as the wearer sashayed between tables or swayed hips-out up the stairs. Walking in them took no special skill. They were not an astonishing feat of fetish or fashion. They did not hurt. They did not threaten to topple the walker. There was no sense of risqué or risk.

They were a pair of shoes. And just as a skin-tight black pleather boot and clear plastic feather-headed mule were objects of note for their daring, for the skill of the girl who slipped her feet into the fetish, the fairy-tale impossible shoe that none but the princess could wear, just as those absurdist gorgeous shoes bespoke something about the owner, these black (cheap) leather shoes with creases and the imprint of the little toe pressing outward were objects of note for their age, their lack of interest, their lack of any fashion sense whatsoever, their day-to-day wearability, their lack of nod to fantasy, their practicality, their sheer dullness in all ways, said something about the woman who wore them.

She was just a woman. She wore a pair of plain black pumps. She didn’t even bother to try. You’d think she’d at least make an effort, the other girls said, whispering to one another about the remarkable shoes, the shocking shoes, the shoes that were, the girls whispered, completely old-school, and they sniffed.

(Just as there are men who like the old-school tattoo — the bluebirds holding a ribbon that reads MOM, the verse of Scripture on the bicep in jailhouse blue, the gray-scale skull on the muscular forearm — there are men who like the old-school shoe. They like the woman who wears it. They like the faint scent of spilled beer and smoke and sawdust it carries, the Patsy Kline jukebox song they hear when they see a woman wearing it, the sort of dance she does, not shocking, just good old fashioned T&A, and enough of each to grab hold of and squeeze. These shoes are part and parcel of their fantasy, and are fetish objects in themselves: The real woman. The old shoe.)

Well, said one girl to the other, what do you expect? She’s been stripping for like a hundred years. She’s ancient. She has to work the split shift. She’s married, has kids, goes home at night to make dinner, etc. I think she does, like, PTA.

This last caused pause; the cluster of girls around the small table, hidden in their haze of smoke, the hiss of their whispers drowned out by the drone of the bass that shook the floor and walls, stared at the woman in the unbelievable shoes, stunned.

The woman on the stage dispensed with her forgettable lingerie (underwear would be more the word) in a bored fluid motion, hooked one leg around the pole, spun, slid down, lay on the filthy stage floor, writhed, rolled, arched her back, and stuck one leg in its ridiculous shoe in the air, as if the shoe was triumphant, as if it had won, as if it said not fuck me but fuck you.

The shameless shoe.

Totally old-school, one girl breathed. How old is she, anyway? Like, thirty?

I think she’s thirty-five.

The girls gasped.

The woman spun the old shoe on her big toe. The song ended. She got up, collected her dollar bills from the edge of the stage, turned her back, and swaggered naked through the swinging mirror, disappearing from view.

PHILOSOPHICAL ASIDE

Of what does a woman consist? Where does her selfhood reside? In some Platonic form Woman, the theoretical perfection of the breed? If so, we human, embodied women are always compared, found wanting, found always lacking and excessive all at once. Or is she the grotesque creature of bodily function that Aristotle describes? Or is she dangling above the Cartesian mind-body abyss, kicking her little legs like Jane on a vine, or is she Hume’s empty stage upon which perceptions play?

This is the impossible task: to enumerate, to number, to name the things that make up a self. This is Leibniz’s muddle of total description. He would say that the only legitimate indicator of identity would be a complete catalogue of a given self’s perceptions: the sights, sounds, scents, tastes, sensations, ideas, thoughts, the entire onslaught of information taken in by a mind, a body, an eye: these perceptions make up the I. The perceiving eye, then, is the I. They are one and the same.

And so she consists of the dark room. The smell of sweat and cologne. The grit and stickiness of the carpet and stage on her skin. The pulse-like throb of bass that shakes the tables, and the sound of ice rattling in a glass. She consists of the feel of the hands on her body. She consists of those hands. She consists of those people, that place.

Hence the impossibility of total description, and the impossibility of her. She cannot be described, named, defined. She contains, as Whitman wrote, multitudes. She contains all that enters her body, her skin, her twitching eye. So do all the watching eyes. So do I.

METHODOLOGY: CONSTRUCTION

I get up each morning and put on my suit of flesh and my face.

I arrange them as they should be arranged, straightening limbs, adjusting musculature, yanking at things that bag, tugging skin as taut as is possible without being inappropriately snug. This I can do in the dark. Next: I turn on the bathroom light and apply my eyes. I push at the putty of my face with fingers and thumbs, pressing cheekbones, chin, and brow bone into their proper protuberance. Then I put on my mouth, open wide, stick in my tongue and teeth.

Last, I colour myself in: scribble irises onto the eye orbs, make lopsided red bow-lips, give myself areolas.

I have never liked my areolas. Too pink. I would prefer more of a mocha shade.

I pinch my cheeks until they are ragdoll red. Thus attired, I go flopping out into the world.

METHODOLOGY: DECONSTRUCTION

But if we are to show how a thing is put together, constructed and fashioned from disparate objects into a seemingly singular Object, if we are to see how the magic is made and the illusion of integration pulled off, we need to take the thing apart, strip it of paint and adornment and this year’s fashions and the thinning skin that holds it together, to see the workings of the machine, how hinge and joint are joined, how seam is sewn. So instead of putting myself together, as one does, as one must, I will take myself apart. I will unhinge and detach my parts, lay them out, articulate each, examine them in the dressing room light, where they can best be seen for their imperfection, their flaws, their fashion faux pas. I am a child pulling Barbie’s limbs from her torso and cutting off all her hair and chewing off her arched little feet. This is dissection. Watch this! I lay myself out on the table, split open my belly, label my parts with their Latin names. There will be a quiz after the striptease. I will get closer to the disembodied core, the elemental, integrated, unshattered self, the single cell, the quark that cannot be further reduced, and I will whip off the final veil: Look! No self!

Oh! my dead grandmother gasps. For shame.

III. PARTS

FEET

My feet are unlovely and Hobbitish, square, squat, and toad-like. The toenails are also square and squat, but obsessively pedicured, painted red, so that the titbit of toe that peeps through an open-toed shoe at least pays homage to the need to keep one’s feet neat, the need to complete the look, and not leave one’s raggedy-ass toes hanging out all unfinished; to leave the part incomplete would ruin the whole.

There is no accounting for the fact that the rest of my feet are rough and dry as rawhide, covered with peeling skin, and faintly orange.

A foot fetishist would find my feet repulsive. But those who fetishise the shoe would find my slavish adherence to footwear fashion, a foot-crucifying fixation on pointed toes and needle-thin heels, quite delicious, for reasons of risk, self-impediment, the forgoing of comfort or practicality in favour of presenting oneself in, and as, a fetish object.

When I have unimpeded myself, unbound my feet, at night, curled up in bed, I rub my feet together, one over the other over the other, like an old woman worrying her hands, or a child stroking the side of her face with the smoothest corner of the sheet. Because of the aforementioned texture of my feet, this rubbing sound goes whoosh, whoosh, whoosh.

I find this sound comforting, as I find the action comforting, as I find the shoes comforting, and generally things related to my feet bring me pleasure, rather than shame.

LEGS

I yank myself apart at the hip joints like a turkey: here we have a drumstick, detached, with its naked white gristly knobs, round muscular centre, and the handy little bone that serves as a handle so you can sink your teeth into the meat of it like Falstaff at a feast.

The thigh is the best, densest, most savoury part. The fashion magazines do not agree with me on this point. But have you ever bitten someone, for example a woman with good thighs, on the thigh? For example, on the inner thigh? There is a salt and a sweetness to the skin. There is a softness between the teeth that gives but does not give way. There is a strength to the thick muscle that runs from knee to hinge of crotch, a tension to the tendon that lashes hipbone to pelvis, and holds the centre of gravity in place.

There: the centre of gravity hangs like a pendulum, swinging steady, keeping time, deep in the centre of the female body, which is whole, which is not hollow, which does not shatter, which aligns itself with planets and galactic tides.

In fact, the centre holds.

HIPS

They are heart-shaped, bow-shaped, shaped like an apple or cello: they are shaped, formed, they are a shape, a form, a building block such as one might find in a child’s toy box, the box of body parts we get when we are small, along with the rest of the shapes, your usual triangles, ovals, and squares. From our set of blocks, we construct constructions. We stack block on block, balance oval on its end. We turn into tiny surrealists, testing the way a shape works in the world, given gravity, angle, and curve. We melt clocks and send men with umbrellas raining through the air.

And we make woman after woman after woman, brows furrowed, trying to figure out where to put her hips. They must be included, of course. They are the sign woman, more even than the breast: breasts, as anyone can see in statuary, are detachable, fall off. But hips, the perfection of smooth curve outward from waist and inward to crook of knee, are a necessity.

The fashions in hips are more variable than any other fashionable part, these variations being culturally specific, and so saturated with multiple meanings about motherhood, sexual desirability, erotic beauty, wealth, willingness, control, that they warrant an essay in themselves, and so I say simply this:

The nude, the painting, the photograph, the aesthetic image of the woman’s hip is not the same as the fetish object of the hip. The hip is not, in fact, a significant part of fetish fashion: for the fashionably fetishised body lacks hips. The fetish body is not a woman’s: it is a girl’s.

And so the fetish objects that adorn the girlish, high, tight hips of the fetish body are those that dispense with curve, dispense with the accentuation of shape and presence and taking of space, dispense with hidden places suggested by curve of derriere and inner thigh: instead the objects expose, grant access, place on display, and play up the childish nature of the fetish object: the g-string, the babydoll, the teddy, the schoolgirl outfit, bobby socks and all.

The eye that finds sexual satisfaction in the visual world of the strip club and pornography mostly has no need of hips. They signify the wrong thing. Instead, the desire sparked by fetish is as surrealist as a child’s, and creates of random pieces the desirable, willing, yielding, the anti-vagina-dentata, a girl whose sexual desirability is exaggerated by the burgeoning, unfallen breast, but whose threatening sexual nature is negated by the absence of hips.

As for myself: I have hips. I settle back into them now: they are comfortable as a collapsing velveteen couch. When I stand up, they will sway, will swing — as Lucille Clifton wrote in her magnificent poem, ‘These are big hips,’ — and will fall by slow degrees. But at least I can move. At least I am not a naked mannequin, impossibly posed, sharp ilium jutting out, hips thrust forward, white plaster hand gesturing casually at something no one has said.

HAIR

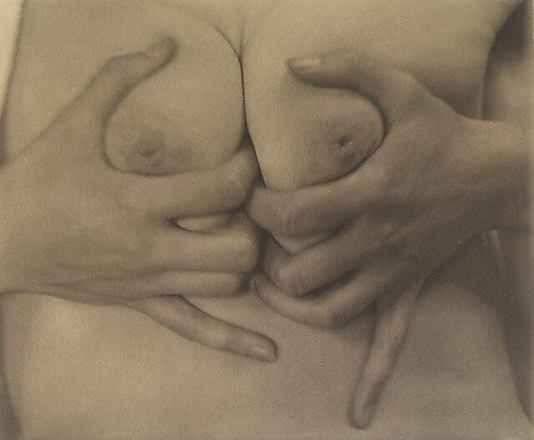

Consider the Stieglitz photo of O’Keefe’s midsection: from the base of her breasts to the middle of her thighs. Her pubic hair is thick and dark; her hands touch one another in a gesture that could be read as tentative, or not. The photo does not show the rest of her body or her face; some would say it’s a dismembered torso; I do not entirely disagree; but I am speaking here of hair. The fashions of it; the meanings it carries, in having or not having it, in shaving v. waxing v. trimming v. shaping it; the intersection of fetish fashion and fashionable norm, the seepage of fetish fashion into commonplace sartorial trends: the porno patch, the landing strip, the Brazilian, the simple bikini wax, the coveted all-out bald; I am speaking of it because I did not know that one was tacitly required to perform these careful and sort of apelike self-grooming rituals until I was well past my pubic-hair prime—and this was because I thought the Stieglitz photo, and O’Keefe’s hair, so lovely in their unassuming, gloriously, erotically real state.

But nowadays I understand. One must manage this most unruly part. One must manipulate, maintain, fashion, turn it into a work of art. So I, too, groom. Sit on the edge of the tub like a hairless monkey, peering down at myself, shaving and plucking till I’m satisfactorily smooth, and even my snatch is a snap-on, snap-off part like the rest.

TORSO, BELLY, BREAST, BACK

It is a fairly ordinary midsection, has the usual parts: breasts and ribcage, belly and back. These are parts I like, and they cause me no shame. But in this middle region of my body, I am never naked. I am always adorned.

I am heavily tattooed and pierced. I have yet to determine if that was a way of using my body as canvas, as site on which to inscribe the image and language I chose; or a way to inflict only chosen pain; or not to inflict pain at all but simply to ornament my flesh; or a way of staying hidden, dressed, even when undressed.

Choose from the following: Adornment, claiming, marring, beautifying, mortifying the flesh. Fashion, fetish, self-injury, shame. Any or none or all of these may be accurate terms. But whatever is the truest term, those of us who wear ‘body art’ wear a second skin. It is a choice; and as with other choices of fashion, wearing and ornamenting the body in this way makes you a certain sort of person, reduces you to a certain sign, and places you somewhere in the social structure. There is some mobility to this; one can cover this part of the body, can don a Cinderella dress and go to dinner in a carriage without causing shock and being turned away at the door; but if the sleeve slips to reveal the lover’s name on the forearm, if the orchid’s lip shows on the shoulder, if the scar is seen, the dress turns to rags. You are revealed as what you are: as what your body says you are and are willing to do, what fetish you choose, what sort of object you are.

FACE

Say, then, that Hume was right: the woman, the fetish body, but above all the face, is that stage upon which perceptions play. It is the blank canvas, empty screen. It is the mirror in which you see reflected what you want: your own desire, projected into the empty eyes gazing back.

But this is the joke! The face falls. It moves. It no longer reflects. It loses its sheen, fails to be the still water where Narcissus falls for his own image, it goes from the smooth, taut, blank beauty of youth to a textured, eroded surface, deeply inscribed with things that signify, that say. It is not an empty sign; and so it is not a fetish as such. It defies the gathering eye. That eye skips over this face like a flat stone.

And that is the body’s fatal flaw, isn’t it? And its most egregious fashion faux pas: it grows old. And in that inevitable progression from smooth object of fetish, to textured human face, we feel a convoluted sort of shame. As we age out of the fantasy of the sexualised child, and lose our capacity to spark that kind of desire, our lifelong identity as fetish object slips. We slip. We falter. We wonder why we begin to feel invisible, faceless, unseen. Many of us, horrified by the crone we see taking our place in the mirror, cannot tolerate it, and attempt, at all costs to body and soul, to stop time.

But this is the point at which we transform, if we allow ourselves to, from object to subject, from fetishised part to integrated whole.

My various parts are arrayed in the dressing room light. The crackling fluorescent bulb casts in garish relief the lumps, the dimples, the hair, the scars. Bodiless, I bend, put the pieces back in place, fashion of my pieces a person—attach limbs at hip joint and shoulder, shrug into my skin, put my head on like a helmet. I stare at my face: so many parts! Where the blank screen was, now I have wrinkles and furrows and eye bags and eyelid folds and parentheses around my mouth and a web of laugh lines that make me look like I am laughing even in my sleep.

Then, intact, wearing the insane, absurd red shoes, I leave the store and stroll invisibly down the street.

Marya Hornbacher is an American writer, and two-time fellow at Yale. She has written extensively about her own struggle with eating disorders and mental illness.

This essay was first published in Vestoj ‘On Shame.’