Listening to her speak is like being at an improvised spoken word performance for one. She’s magnetic and effusive, and it’s impossible not to be charmed by her. With her is her ‘fabulous husband,’ who from time to time interjects to offer some information that she’s forgotten: ‘cell phones,’ ‘Ronald Reagan,’ ‘MTV.’ In the 1980s she was among the fashion world’s first ‘supermodels,’ and one of the first African-Americans to work with Karl Lagerfeld, Thierry Mugler and Yves Saint Laurent in Paris.

Everyone is always so interested in what it’s like to know stars. They ask, ‘How is it to know Karl and Halston and Stephen Burrows and Antonio Lopez, and Josephine Baker and Miles Davis?’ Well to me they’re human beings with a heart that beats. It’s the same for everyone: you stack up the good memories, and then you struggle through stuff till you get to the next good memory. You’re trying to find the next person who’s going to relieve you of the burden of loneliness. I think everybody’s alone, they want love, and they’re putting out. Stars are no different: they make things, they cycling around on bikes, they make stories out of their lives, because what – are you going to sit still at home and die? No!

The Eighties was a sexy time and a very dark time too; people started wearing a lot of black, a lot of leather. Who was president then? I don’t remember, I was travelling so much. I think it was a movie star, there was a movie star who was president, wasn’t there? Reagan? Yes, that’s it. He was a movie star, so everybody could relate to the big billboards. It was a movie star kind of world. Did I feel like a star? I’m always out there somewhere twinkling. You know I just twinkle twinkle. I never felt like I was going to land on earth and make a dent in the planet, oh no I don’t feel like that at all.

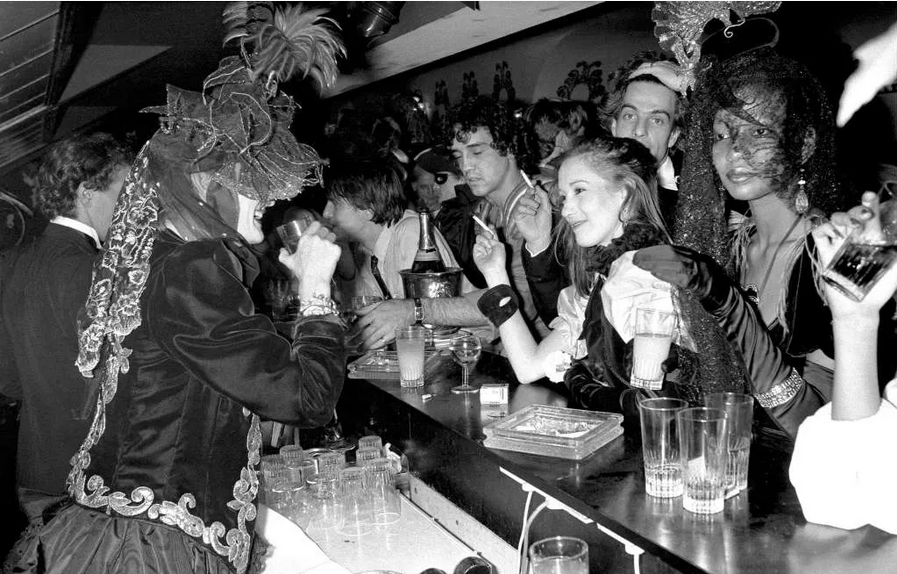

I spent a lot of time in Paris in the early Eighties; everyone was going to Le Palace. And it was like a plague had hit because of AIDS. Everyone was living at night and wearing sunglasses during the day. Then people started wearing sunglasses at night too, which was very odd. Everybody was so important and arrogant, so full of themselves with those sunglasses on. Like, ‘Oh I’m too good for you to look into my eyes,’ ‘Oh you mustn’t see me.’ ‘Don’t take my picture!’ But they arrived to have their picture taken, hiding behind the leather and the glasses. New designers were making forbidden, provocative looks, it was powerful, you know. Women were coming down the runway with giant shoulder pads looking like they were from another planet. I remember it being a bit painful to wear those looks: they were heavy and masculine, like shields. Everything was sort of S&M: iron and metal and steel. We were wearing armour. Those synthetic drugs were coming around but they weren’t that popular yet. It was all about cocaine and heroin. Very bright, creative people got carried away with the times and ended up leaving too quickly. ‘Live fast, die young,’ as they say. Ooh! Here comes a lady with a baby – will I be able to talk? Get them out of here! (Laughs) Babies are innocent, they mustn’t hear this kind of talk. I’m going to be quiet for a minute, out of respect for the budding population of the world.

You don’t have to suffer you know. You should live well, that’s the whole deal. But things were colliding then. All the history that everyone had absorbed, they were trying to live it. Young stars were reading about this or that one who came before. They were reading about how great they were, and then they wanted to live up to the ideal. In the Eighties people were already at the pinnacle, the height of their careers. They had reached the top of the mountain, and then where were they going to go? I avoided all of what came next though. I fell in love and got married. I lived on a mountaintop and raised my kids with my fabulous husband, and lived very simply. I had a model agency and taught girls to walk. I lived like that for twenty years: on the mountain top, in a small village above Stresa in Italy, with a beautiful house looking out over a lake. I just skipped over the Nineties.

In some ways the superstar models ruined the business. They started charging the designers so much money, they put everyone out of business. A handful of girls were sucking up all the money, and the new girls coming up were getting pennies. It really changed the business. You could get ten girls for the price of one. All these young girls showed up on the scene; they were underage and had no kind of guidance. The business got really nasty; the playboys came in and tried to get the young girls. The girls would go to parties, and they’d be given drugs and disappear. It was hellish. I had my agency then so I saw it first hand. Fourteen-year-old girls were coming out of Russia and the Slavic countries, China and Brazil and wanted to stay in Italy where life might be better for them. I saw these girls trying to survive and it was oh so sad. Most of the time you knew they weren’t going to make it, because of the super – what do you call it – the supermodels. In the Nineties people were moving faster and they wanted to spend less money. The age of the middlemen begun. It used to be that the designer would find somebody and build them up, but now you’ve got to go through ten people to even meet the designer. There’s a casting door – and then door after door after door. Fashion became part of show business; it wasn’t a cosy house anymore, it became a factory. A conveyor belt of girls would go past the booker. Models booming in from all over: twenty, thirty, forty, one hundred girls standing in line, trying to get booked. It’s so pathetic, it’s so sad. Most of the time the girls don’t even know what they’re doing. They’re just so young. You get girls walking like, ‘Duh. Where am I?’ ‘I don’t know what to do.’ No sense of anything.

Were there moments where I felt despair at the state of the industry? Well that kind of negative thinking will just destroy you. I can’t have that, no. It’s a question of character, you know, how you feel and where you let your mind go. You could be in one culture and be the worst thing, and then go to another and be the best. That’s why we travel like nomads in the fashion world, we just keep fluttering around like butterflies. ‘Okay you don’t like me? Ciao, I’ll go somewhere else!’ We’re like dogs, ‘Oh I’m not getting a bone here? I’ll go to the next table and look cute, maybe they’ll adopt me!’ I feel like a pet for adoption sometimes, you know. Sometimes I think people want to pull the rug out from under me. You get somewhere in this world and it’s, ‘Oh, pull the rug out from under her, and let’s see how she falls!’ But then I just think, well I’m not standing on a rug anyway, I’m walking on clouds! (Laughs) And that’s when you get married, have kids and support yourself in another way, you know?

Beauty is my goal: to find the most beautiful things. Whether it’s inside a person, or a flower, or a place, or the clothes they wear, I try to find the most beautiful thing I can in the moment. I have this needle inside me like a compass that says, ‘due north, follow your star, this way, this way!’ My daughter is a model now, and when she gets tired I always tell her, ‘Take a break, rejuvenate your spirit, because nobody wants an empty cornflake box or an empty potato chip bag.’ In a way, we’re just bags, full of spirit, and then somebody puts a label on and you get out there and you push the product. I’m just the container you know, that’s all I am. I learnt that from Joan Crawford. She didn’t mind peddling Pepsi Cola. But I feel like a perennial; they planted me in the right soil and I just keep coming back year after year. I serve a purpose, you know me – I’m just a flag pole. People put their flag on me and I fly it proudly. That’s part of being a model. The rest is about understanding the people, you know, what’s going to make them happy? What can I bring to the room? How can I entertain them? That liveliness a model can bring is so important. I’m like a fruit. I’m still on the vine man. I’m just a banana hanging in the tree, with the rest of the crazy bananas.

Anja Aronowsky Cronberg is Vestoj’s publisher and editor-in-chief, as well as a Research Fellow at London College of Fashion.