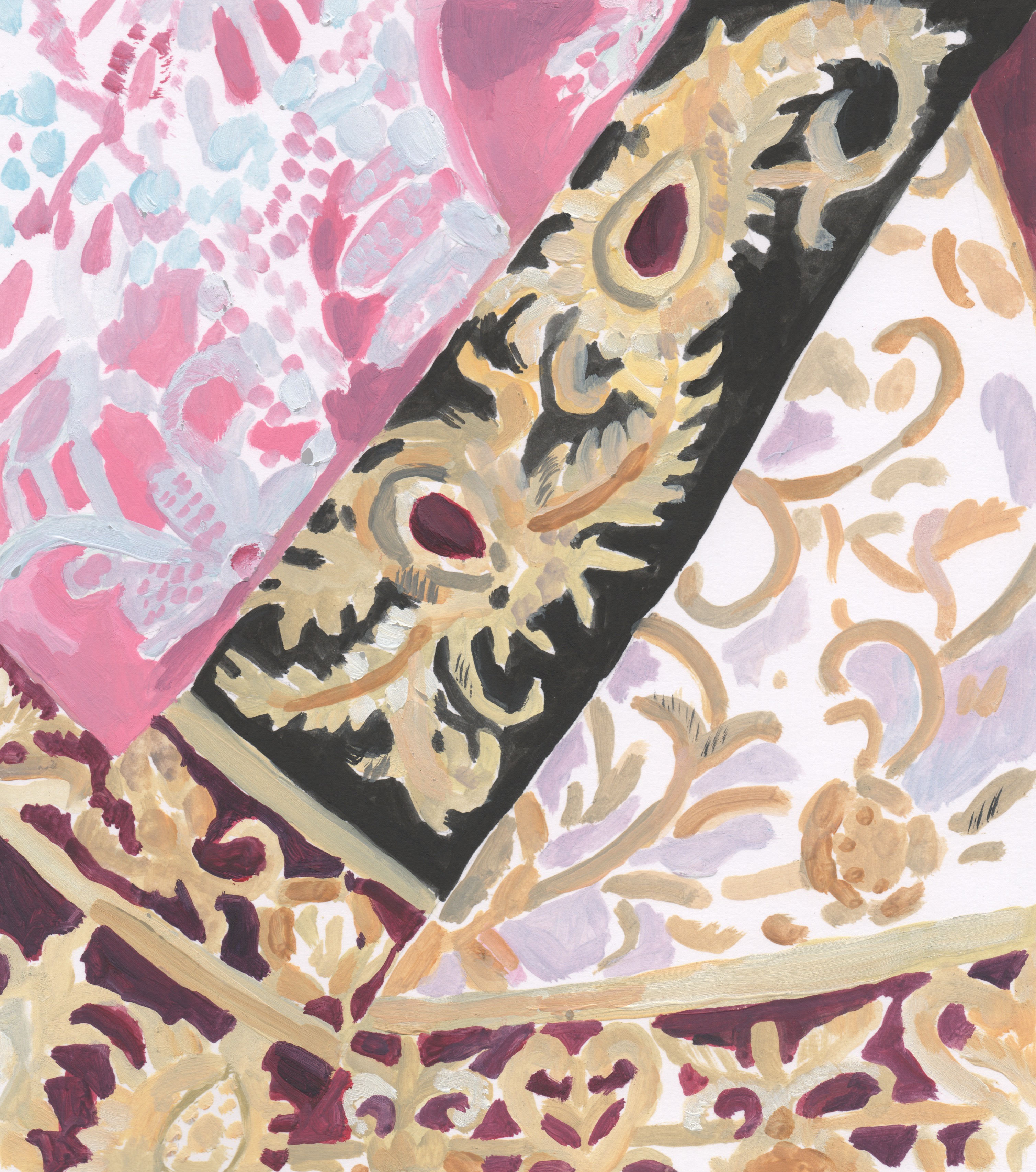

IN THE SPIRALLING LANES of Byculla – a bustling neighbourhood in Mumbai – is the workshop of bridal designer Mujibar Rehman Khan, an expert embroiderer and dressmaker. He sits down on a sultry Mumbai afternoon to unveil the process of making his elaborate bridal wear garments, and the changing landscape of this specialised craft. The Indian bridal industry is teeming with opulence and fine craftsmanship, but above all, tradition: the Lehenga Choli – the name of a bride’s traditional wedding attire – originates from the Mughal era, referring to a voluminous floor-grazing skirt, customised with hand-crafted embellishments and worn with the cropped bodice, or Choli. The bride is then draped in the Orhni, the long stole which covers the head and shoulders, and completes the outfit. In all Indian wedding ensembles, red is traditionally the dominating shade: an auspicious colour, according to Hindu traditions and belief, which signifies courage.

***

I’ve been in the bridal business for twenty-two years now. My father is a farmer and a singer and we hail from the Howrah district in West Bengal. I initially began as an embroiderer for a small workshop and I trained for fourteen years under Miss Zeenat, a designer who had been in the business for decades. Soon after, her daughter became engaged, and I had the opportunity to design her wedding outfit: a powder pink Saree with silver Dabka work. The outfit reflected an infusion of Western elements, like sequins and Swarovski crystals, with traditional techniques like Zardozi, Indian metallic thread work. We were inspired by traditional jewellery designs, and we brought in samples that we transformed; the design of an uncut diamond necklace became the embroidery of a neckline, or a detail on the folds of the Lehenga. These early stages were very experimental. In this business there is no right or wrong, but it’s important to recognise what’s desirable to the client. We never used to start off with a clear result in mind; it was always an organic thought process.

Under the guidance of Miss Zeenat, I learnt the complexities and techniques of the business; I then decided to open a workshop of my own. I could only afford to hire one embroiderer who came to me as a teenager, and today he still works for me. Over time, I developed a loyal clientele who approached me with private orders. Young brides-to-be accompanied by their army of friends and relatives – often led by a tight-fisted mother – flocked to my workshop months before the nuptials. They would come with me with cut-out images from bridal magazines or newspapers asking to look like their favourite Bollywood actress.

There were very few popular bridal designers back then, so fashion magazines were the main source of inspiration. It was a less demanding business then; there was a sense of trust in our design capabilities and the clients would always walk away happy with the dress. Nowadays brides often shop from the high-end boutiques, but back then nothing was ready-to-wear, everything was created from scratch according to the client’s wishes. We would show the client a variety of patterns that we would then customise. We worked with a tailor who would stitch the entire outfit according to the bride’s instructions – from the cut of the Lehenga, to the pattern of the Zardozi embroidery. We would make individual swatches of the embroidery for the client’s approval before creating the outfit. We were never stingy with our work; a good customer relationship is vital because our business survives through word of mouth. I used to have clients from all religions and each had their own tastes: Muslim brides desired work that was shiny and contemporary – satins and silks in shades like lavender and emerald – and Hindu brides often opted for more traditional fabrics such as Bandhini and Zari in colours like gold and red. Nobody wears black though – it is considered inauspicious.

My specialty is Zardozi work; and to create a Lehenga with this technique is a highly time consuming process that requires deft craftsmanship. We often employ expert craftsmen, Karigars, who have been in the business for a minimum of eleven years. The Lehenga is a very opulent decoration to the fabric of the outfit; three-dimensional flower motifs seems to be the trend today. Swarovski work is also very popular: these crystals aren’t always available locally and often have to be imported from Japan. It’s like making a piece of jewellery: the placement of the crystal is so important in order to get the most from its sheen. To produce this work is very expensive, so we can only cater to stores that have a heavy footfall. To make an entire Lehenga can take weeks and the skilled hands of fifteen artisans.

Recently, there has been a Westernisation in terms of fabrics and silhouettes accross the Indian bridal industry. Twenty years ago there wasn’t the same use of silhouettes and materials. Back then, we would exclusively use traditional fabrics like brocade, Bandhani and raw silks with Zari work. Women shop for their bridal outfit differently too: high-end bridal boutiques have become the standard. I don’t feel they are producing an extraordinary garment, mostly they run their business off the marketing and brand value attached to their names. We can’t afford that sort of publicity. A lot of craftsmanship in the industry is also waning with modern technology. Patterns are now computerised, but while innovation is booming, customers are beginning to lose appreciation for hand-embroidered bridal wear.

With the emergence of large designer stores, my private client base has diminished and I now only cater to boutiques. I miss the old days where there was more enthusiasm and creativity involved in creating a Lehenga, but today’s work is more stable. I have a family to support even though the old romanticism of the business has faded away.

Tanya Mehta is a Mumbai-born writer.

Anna Skeels is an illustrator based in London.