I HAVE LONG CONSIDERED sewing to be my mother’s career, though she seldom refers to herself as a seamstress – a term she pooh-poohs with a mix of modesty and contempt. She prefers the more active: I sew, subtly implying, therefore I am. I assigned her the title out of necessity, in response to the many requests I received as a child regarding my parents’ vocations. Any time I made a new friend it was only a matter of time before her parents would curiously pry into my family life, wanting to know what sort of people their children’s friends came from. I dreaded this unavoidable line of questioning because neither of my parents really did anything in the traditional sense, as in a daily job that yielded a legal paycheck that was then used to pay bills. I also bristled at calling them ‘my parents’ because they were not a unit, nor had they ever been, but this was 1980s small-town America. Everyone still had two parents unless one of them was dead, which was at least a good excuse not to have a real job.

My father was generally out of the picture, so his career could be anything I wanted it to be. He usually amounted to a ‘house painter,’ which was at least partially true, though debatable as to how much of his total income was derived from this pursuit. That my father painted houses was often presented to me with a tone of knowing amusement, the way Tony Soprano works in ‘waste management.’ My father did not own a truck or a ladder or perhaps even a pair of overalls but I did once see him paint a house (ours), and this was evidence enough for me to fabricate his livelihood with some conviction.

My mother’s career had more of an evolution. ‘Tell them it’s none of their business,’ she’d say, when I sought her advice on how to respond. ‘These parents have some nerve.’ She instructed me to tell them she was a ‘homemaker,’ but this answer felt inappropriately antiquated. Homemakers were the women in black and white sitcoms on Nick at Nite, women who ironed all day and had dinner waiting for their husbands when they returned from work. My mother ironed a lot, but mostly loudly patterned slabs of fabric purchased from mail order catalogues. There was no husband.

Since she sometimes got paid to sew, I deemed my mother a seamstress. This title called forth a sort of romantic grittiness emblematic of Rosie the Riveter; sewing was a feminine trade but it was still a trade, one that involved machines and tools and sometimes bloody, calloused fingertips. Sewing suggested industry, craft, resourcefulness. Having a seamstress for a mother tapped into one of my many childhood historical fantasies of living off the land and fending for ourselves. More importantly it was a good enough answer to shut the parents up. It even made some of the other mothers a little jealous. I wish I could sew like your mother, they’d say, admiring some or other handmade garment I was wearing. I’d savour those moments, perhaps even do a little catwalk turn, pleased at my ability to render at least one of our unique familial circumstances into a social commodity.

***

My mother has not held a job in nearly fifty years. This is not because she chose to be a stay-at-home mom or enjoyed independent wealth or relied on a man to dole out an allowance. She had four children from different fathers, none of whom contributed financially in any notable or legally mandated way. We lived with my grandmother in her once-stately New England home in a small Connecticut town in which we, as a familial economic entity, were ill-fitted at best. The bills were paid by way of my grandmother’s social security allotment and my mother’s monthly welfare check. She later fought and won the battle to receive disability benefits for a health condition of which she is neither proud nor ashamed.

I’ve placed this up front so that the question of our finances will not distract from the point of this story, which is less about economics than it is about drive. We were poor and happy. And my mother was jobless but prolific. She woke every day between four and five in the morning, made coffee and began to work. That is: to sew. She did this for several hours a day, hunched over the machine’s dim yellow glow or splayed on the floor slicing swaths of fabric on a ragged cardboard cutting surface, her reading glasses perched at the end of her nose. Sewing was as much a part of our existence as, say, football or prime time television might have been to other American families. The foreign language of dressmaking snuck into my vernacular at a young age: darts, batting, selvage, ric rac. I knew how to find a bias and how to tell the difference between chevron and houndstooth. Ours was a home built on industry, the sounds of her sewing machine the accompaniment to our childhoods: a mechanical melody that signified the day had begun.

The seeds of my mother’s sewing habit were planted in the late 1960s, when she had a job working as a model at a boutique, back when boutiques routinely brought designers in to preview their lines on live mannequins. I picture her standing on a small pedestal, blonde and svelte, focusing on a distant object in the room while the men debate colour and trend, shape and profitability. Just out of high school and broke, she could not afford any of the clothes at the boutique, or at any boutique. At some point she realised that it made more sense economically (and, perhaps, politically) to make clothes rather than model them.

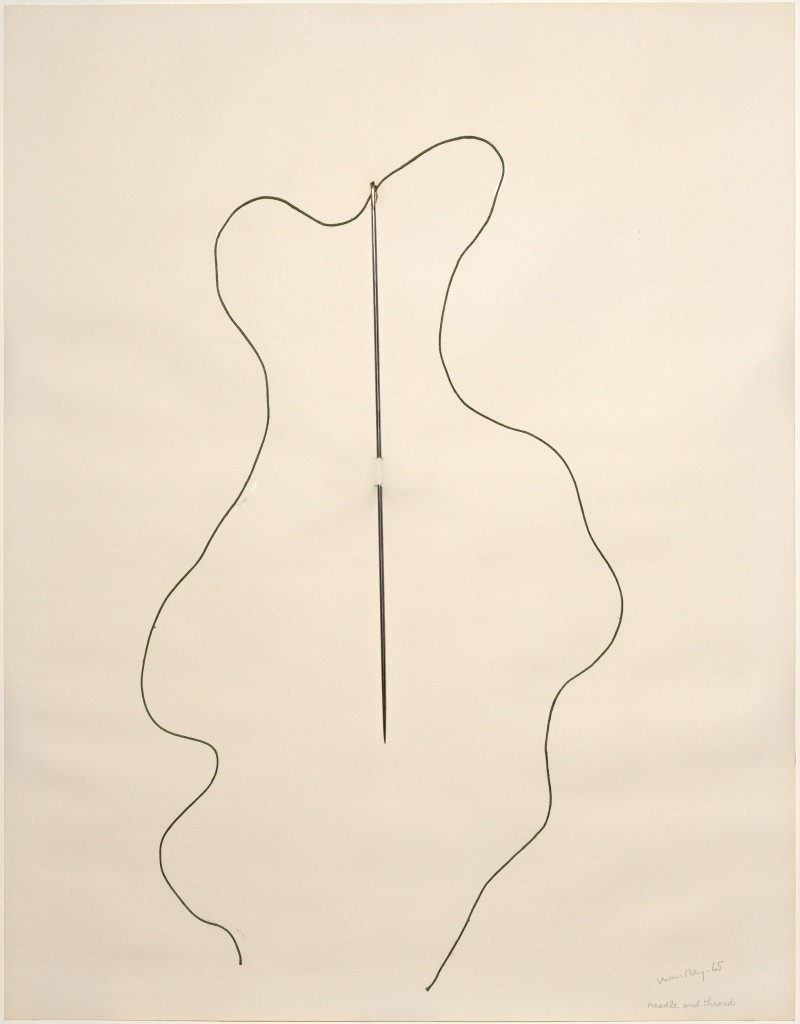

Over the next few years she taught herself using The Vogue Sewing Book, a hefty 1970 tome that elevates sewing to the art of sculpture. ‘The creative forces necessary to make flat, two-dimensional fabrics take on strong, structural three-dimensional shapes are no less important than those required to chip marble or mold clay,’ writes author Patricia Perry. ‘A fashionable woman is aware that she is a three-dimensional form that can be seen from all angles.’ Reading it now I can visualise the blueprint of my mother’s attraction to sewing in between Perry’s lines, so confident in the artistry and precision of this craft. At the time she was living with a man named Jimmy to whom she had eloped right out of high school. It was Jimmy who purchased her first low-end sewing machine – one of the more generous moments of their marriage; they would divorce by the time she was twenty-three and she would return to live with my grandmother in her Neo-Colonial New England home, the same home where we grew up and where she still lives now. She would eventually invest in a sturdier Singer model, which she would use for the next forty years, until its individual replacement parts became obsolete.

The Singer lived in our basement, built into a table at the bottom of the staircase. Threads hung above the machine, pointing skyward from a panel of wooden knobs; notions and zippers cascaded from uncloseable drawers below. Beyond lay her workshop: an ironing board, a ghostly female dress form and, of course, fabric. An early memory recalls the fabric being neatly folded and confined to a set of built-in shelves, though that quaint set-up could not support her rate of accumulation. In basement memories of later years, fabric encroaches all available surfaces: a derelict mid-century television set, a broken recliner, a large table that once provided a landscape for my brothers’ Star Wars toys. When the surfaces ran out the fabric grew in piles on the course crimson carpeting. Every so often heavy rains penetrated the house’s crumbling foundation and we were all enlisted to gather cuts of gingham and chiffon from the floor and pile them anywhere they would not be tainted by floodwater.

Back then she acquired most of her fabric from hodge-podge mail order catalogues and small, family-owned shops that had entered the twilight of their years, places with names like Miller Fabrics, McCrory’s, Horowitz. JoAnn Fabrics would eventually wipe these from the map, but at the time JoAnn’s was the JCPenney of fabric stores: decent prices but a rather generic selection geared toward a suburbanite demographic of which she did not consider herself a part. It’s important to distinguish that my mother was no Suzy Homemaker who spent her afternoons hemming and gathering bed skirts; she took herself to be a fashionista, pursuing a craft that required skill, patience and taste. Every Sunday morning was spent watching Style with Elsa Klensch, a CNN show covering international fashion trends, hosted by Australian-American journalist, Klensch, known for her contempo refinement and her blunt, Depression-era black bob. While our neighbours read the New Haven Register, we kept an unlikely subscription to the New York Times, predominantly for its esteemed Fashion section. She rolled her eyes at the type of women who frequented JoAnn’s, bored housewives who might fill their downtime embroidering pillows or – the hobby whose value it has taken her years to recognise – quilting. She often described those women as ‘beige,’ in other words, stripped of colour and couture.

My mother demanded a life of colour as though it were an act of defiance, a revolt against the ivory shackles of her Connecticut existence. She’d routinely fall in love with an obscure hue – chartreuse, fuchsia, ultramarine – and it would sweep its way through our everyday, making appearances as a wrap dress or a purse or an oven mitt. The house itself embodied her penchant for jewel tones and rich, velvety hues – the result of a remodelling that she and my grandmother undertook after her father’s death in the early 1970s. While posthumously going through his things they discovered a substantial wad of hidden cash. Instead of investing in practicalities, they used the money to revamp the home’s interior, erasing all traces of the various shades of vanilla and ecru that had defined the home’s mid-century aesthetic and, more subtly, their restrained domesticity under my grandfather’s heavy hand. They ushered in rolls of paisley patterned wall paper, blood red oriental rugs, deep purple drapes. Teal glass netted buoys hung from curtain rods. Tassels dangled from satiny gold lampshades. Daylight crept in through vintage lace hung over long vertical windows. ‘Your grandmother wanted to open a tea room,’ she tells me now, as though – if it weren’t for pesky zoning laws – that aspiration might have made it past the phase of a wistfully decorated dream.

***

My friends’ mothers did not sew because they didn’t have time and, more importantly, didn’t need to; for the white middle class, buying clothes was a privilege and a rite. That we could not afford that privilege was a reality obscured from my worldview, concealed, perhaps, under the bounty of loose yardage. I did not take issue with these circumstances until middle school, when it became socially imperative to own a pair of jeans with a little leather tab advertising their origin. Up to that point, I enjoyed what I believed to be the luxury of a live-in tailor.

This is not to say my mother’s talent catered to my every fashion whim. Our maker/model relationship was symbiotic in nature; though not the eldest child, I was the first daughter, and with that came the opportunity for her to fully realise her wardrobing fantasies. With the exception of underwear and socks, she constructed the entirety of my grammar school closet. This was the 1980s, so the selection was not short on pizzazz: pullover sweatshirts boasting multiple sequined appliqués, leggings in various vibrant hues, flowery summer dresses with full skirts; in winter there were tie-dyed ski jackets, in summer neon one-piece swimsuits, in spring shiny vinyl ponchos; leotards for gymnastics, bike shorts for gym class, something called a ‘skating skirt’ for trips to the roller rink before it shut down. And then there was the matter of ‘dress-up’: a metallic lycra tube top, a faux-suede zebra-print skirt, a white fake-fur coat with matching muff, a sleek pair of purple elbow-length gloves. Sometimes I looked like Shirley Temple, other times more like Cyndi Lauper.

Despite her knowledge of high fashion, she understood little of the style that guided actual suburban children and dressed me according to the trends in pattern catalogues. Most of the time I blended in but the moments of discord were baffling. For the last day of second grade, she made me a dress from a Vogue pattern, insisting it represented the latest in 1988 children’s fashion. This may have been true for children who spent their weekends at FAO Schwartz, but was not the case for those of us in a small Connecticut town seventy miles up the Metro North rail line. The dress was a pale shade of pink, came just above the knee and had sort of an avant-garde twist: T-shirt-length sleeves with a cut-out on each shoulder, exposing an almond silhouette of my olivey skin on either side. Still young enough to be naively confident, I went to school convinced my outfit carried an air of Hollywood; at the least it resembled something the older, more stylish sister on Charles in Charge would have worn to a school dance. This, however, evaded the other children, who only looked at me confused and kept asking why I had holes in my shoulders.

I did not then, nor do I now, possess my mother’s fashion forward sensibilities. Short of a few uncharacteristically brave periods, I have generally dressed in some variation of jeans and T-shirts. For this reason, the planning and crafting of my Halloween costumes presented an opportunity of great import, one that rivalled the dressing of Oscar nominees for the red carpet. My regalia ranged from traditional (a witch, 1985; Dorothy Gale, 1987) to exotic (a gypsy, 1989; a can-can dancer, 1991) to popular (Bugs Bunny, 1986; Morticia Addams, 1992) to age-inappropriate (a ‘greaser,’ 1990; Jessica Rabbit, 1988). A book of costume ideas floated around our house for a while, but the selection was entirely up to me, which exemplified my mother’s lack of a filtering mechanism. When I insisted upon dressing as the buxom Jessica Rabbit, she accepted it as sort of a professional dare. Made from body-clinging magenta spandex, the dress had slits up either leg to the mid-thigh and internal boning to support its strapless structure in the absence of my not-yet breasts. We found a pair of small purple heels at the local Thom McAn and stained my black hair red with an aerosol can of tinted spray. I was eight. When I showed up to school in that get up, proudly puffing out my flat chest, my prim, long-skirted third-grade teacher looked at me as though I had walked out of a John Waters movie.

Our school held a Halloween parade during which children shuffled clumsily around the gymnasium while parents watched and snapped photos with clunky black cameras. There was no formal costume contest, only the subtle, unspoken rivalry that exists among parents. My mother’s costume artistry indisputably outmanoeuvred that of her contemporaries, though she never volunteered the fact of her craftsmanship unless prompted. Another mother might say, Oh my, look at Candace’s costume, did you make that?, at which point she would smile and affirm their suspicions, patiently awaiting the look of amazement that came over their faces. I find it difficult to convey the tone my mother used around the discussion of her skill. It was not quite humble, though not pompous either. More like confident, in a way I witnessed her express only regarding sewing, as though she were saying, I’m no superhero and I can do this. What’s your excuse?

***

A modest, undocumented income came our way from my mother’s sewing, mainly from a small dry cleaning business a mile down the divided highway. The kind of place with an automated clothes rack and rows of glistening washing machines lit by suspended televisions. When someone showed up with a tear or needing a hem, my mother was enlisted to mend the stranger’s clothes, returning home with a shoulder-padded blazer or a shockingly large pair of men’s suit pants. Items that looked as out-of-place in our home as would the owners of the garments themselves. Often she and I would make up stories about these never-to-be-seen clients, assigning them comically villainous nicknames and farcical storylines that elevated what we presumed to be their humdrum existence.

When I was eight or nine she secured a regular sewing gig for a woman named Sherri, whose then-incarcerated husband Sonny had once run with my father’s disreputable crowd. Sherri and her two daughters lived in a house I likened to a mansion because it had two staircases and a marble fountain full of fluorescent fish in what Sherri referred to as the foyeé. The house occupied the last lot on a private cul-de-sac whose unmarked entrance we must have driven past a thousand times, though I’d never noticed it. The first time we visited I felt I was being shown a room in my own home, hidden behind a door camouflaged as a bookshelf.

Sherri enlisted my mother to sew various frilly dresses for her daughters, Lydia and Penelope. I’d tag along on trips to drop off or size a garment, which worked in both our favours; my mother used me as a buffer in the likely event that Sherri trapped her in a tirade of Sonny’s indiscretions, and I got to briefly enjoy the luxuries of her daughters’ privileged existence. Penelope was barely out of diapers but Lydia, seven, already exhibited a breed of sophistication I will never reach. She rode horses and slept in a canopy bed and ate with a napkin on her lap. An ordinary visit began with a housekeeper preparing us juice and Pepperidge Farm cookies that we enjoyed at a tea table overlooking their vast and flawlessly emerald lawn. Afterwards we’d retreat to her bedroom, which boasted a colour television and several shelves displaying plush stuffed animals whose fur had not been tainted by the drool and snot of love, nor did they display any evidence of having been touched at all.

It was Sherri who helped my mother profit briefly off the unprecedented popularity of scrunchies in the late 1980s. By the time these clownish hairpieces hit suburban fashion circles my mother had perfected the art of scrunching; I boasted a collection that could have equipped the entire female cast of Saved by the Bell. A diehard advocate of my mother’s designs, Sherri introduced her to a man who owned a small boutique nestled into a nearby shopping plaza. He was impressed and began selling a line of her hair accessories: gold lamé scrunchies, bobby-pin roses, clips bearing the weight of huge, taffeta bows. I remember visiting the shop and admiring the display of her work, priced at eight to ten dollars a piece. I thought about the more elite mothers in our town unknowingly modelling accoutrements made by the mother of that peculiar long-haired girl their daughters only regarded with curious disdain.

High off our short-lived scrunchie fame, I pestered my mother about advancing her sewing career. Why not? She was talented and people were always impressed with her skill. I fantasised about her opening her own boutique, a place where I could hang out after school and eventually be trusted to operate the cash register. When I presented her with these business plans she waved me off as though I were proposing something fiscally outlandish, like installing a heated in-ground swimming pool. I did not understand her limitations or the investment required to start a business or the reasons she only accepted cash for her work. I thought her refusal was stubborn and misanthropic and that she was hell bent on stifling the recognition I would earn as the daughter of a local business-owner. Even the four-eyed, frog-like children whose parents owned a mediocre pizza parlour were granted social immunity for their connections.

This, however, was not my fate or the fate of her designs, which went largely unrecognised. Small-town celebrity did not concern my mother. She maintained an air of exclusivity that I then considered disproportionate to our station in life. It was unfathomable to me that someone could be satisfied with their work in and of itself, free from remuneration or, at the least, public validation. She seemed content appraising her talent on our gratitude alone or, more likely, enjoying the uncomplicated satisfaction she got from the act of making, free from the judgements of a local audience she assumed to be unworldly and absent of taste.

Like most assumptions, this one is both gross and empirical, drawn from the observations of a lifetime spent in the same small town, the kind of place that favours blending in over standing out. My mother adamantly denounced that lifestyle; she was much more in her element in New York’s Garment District, bargain shopping in cramped fabric stores on the upper floors of creaky, un-air-conditioned buildings. Perhaps being condemned to a landscape of muted taupe and slate fuelled her appetite for a life of chromatic insubordination. One year she grew tired of the gray New England winter and planted fake flowers into the earth in her front yard. ‘Now they’ll bloom all year long,’ she said.

***

The recent proliferation of DIY culture has encouraged my mother to embrace the existence of like-minded rebel crafters and neo-seamstresses. The art of making is now commonly accepted as cool, resourceful and pioneering; perhaps it always was all those things, but lacked a mobilisation that only the web could engender. Instead of existing in a sub-rural vacuum, her creative undertakings have relocated to a global spectrum, somewhere between Etsy and the Colette Pattern blog. She proudly boasts an Instagram feed decoupaged with photos of her modelling homemade frocks, posed in front of colourful backdrops like brightly painted garage doors or vintage cars. She once had me photograph her next to a cobalt blue Mustang parked in the lot of a car rental shop while the clerk watched, confused, through the front window.

Occasionally she tosses out the idea of starting her own sewing blog, but when I offer to help her realise it she brushes the project aside, making excuses that she doesn’t have time or gets too frustrated with the photo editing apps on her tablet. I sometimes wonder whether she would have taken advantage of a venue like Etsy, had it come to be thirty years ago, but the answer is probably not. Marketing her skill would have meant becoming a part of the same system she spent a lifetime rejecting – a renunciation that is part humility and part insubordination. In her mind, sewing has always been an act of rebellion, a way to combat the consumerism that blanketed the latter part of the twentieth century. She looks upon the recent crafting revolution with a sort of stoic and amused consent, as though pleased the zeitgeist has finally caught up to her tenacious idealism.

I am often asked whether I inherited my mother’s sewing skills, as though such a thing is passed purely by genetics. While I can hem a pair of pants and have been known to make the occasional tote bag, constructing a garment from scratch is a feat outside the boundaries of my time and patience. I cannot unknow that purchasing a used shirt from my local thrift store will always be a more economical choice for someone with my skill and availability. I have a child, a job, a husband and the little writing career that could; pursuing a craft beyond the margins of hobby is a luxury for which the path I have chosen makes little room.

That my mother does not consider sewing an occupation or a luxury is pivotal to her pursuit. She would hardly describe her life as luxurious – so full of fiscal and circumstantial limitations – but her ability to devote herself to sewing is, in some ways, an endless exercise in self-care. The result is a lifestyle suited to both the aimlessly rich and the shrewdly unrich, lavish with eccentricity and free from the albatross of conformism. Perhaps sewing represents that most elusive and rarely indulged of lifelong hungers: a calling. I sew therefore I am. And a calling is not hereditary. If I am lucky, I have instead inherited her abhorrence of the status quo, her indefatigable quest for ingenuity, and her willingness to resurrect a paisley cushion with floral corduroy, knowing full well she can only partially conceal its state of disrepair.

Candace Opper is a writer, an advocate, a mother and a digger, bent on unearthing the insights buried between personal and collective histories. Her forthcoming novel, Certain and Impossible Events, will be published by Kore Press Institute in early 2021.