FOR MOST OF US, our closets are home to sentimental garments with a story to tell alongside clothes we tend to forget. Wardrobes reveal the complex and often contradicting perceptions that dictate how we emotionally prioritise our clothing. Within a fashion cycle that favours the production of one-off styles in an unending quest for the new, consumers often feel disengaged from personalising their clothes or cherishing them after trends expire. Enter the ‘Italyan Avlusu’ project, orchestrated by theorist and designer Otto Von Busch and the Turkish artist collective Oda Projesi. The Istanbul-based workshop illuminates a consumer-initiated pathway to sustainability that winds beyond the stigma of eco-friendly fashion. The workshop was aimed at decoding the dialogue between emotional and material durability, revealing the potential for meaningful exchange between garment and wearer.

Despite the hype surrounding sustainable fashion since the turn of the twenty-first century, sustainability still seems like an afterthought for most of the fashion industry. Material culture often aestheticises social and environmental issues to create a desirable image of sustainability.1 From this emerged the popular trend, ‘green is the new black’,2 which pioneered eco-chic fashion that promised to change the world through style. Concerned by such ‘myths of expectation’3 created by fashion, Otto Von Busch collaborated with Oda Projesi to establish the Italyan Avlusu workshop. The project was established in Istanbul, Turkey and operated from February through March in 2004. The workshops were situated at the Oda Projesi studio and led by the collective’s resident artists. Italyan Avlusu mainly targeted the local consumers, including children, but the project was also open to international participation through the now-defunct Oda Projesi website. While Italyan Avlusu took place ten years ago on a small scale, the project’s aim to embrace capacities over commodities is a valuable lesson in the importance of consumer participation to building a sustainable fashion industry. The purpose of the project was to establish emotional connections between a garment and its wearer by encouraging customisations, investigating a central problem with fashion: garments move from wardrobes to waste bins when they seem to no longer fulfil a perceived desire, even if they still satisfy their functional purpose.4 The current fashion system is underpinned by a cradle-to-grave lifecycle5) to support rapid consumerism. In objection, Italyan Avlusu endorsed the return of old clothes to closets, reviving the emotional value gained through wear.

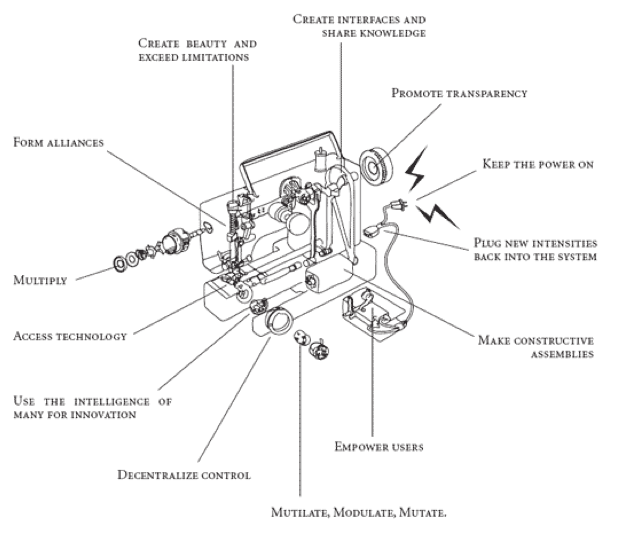

Personalisation got political as Itaylan Avlusu encouraged participants to hack the fashion system. Old garments brought along by participants were reassembled, deconstructed, embellished, fitted or repaired on-site. Curiously, the workshop revealed that a great amount of courage was necessary for participants to make customisations to their clothing. Most participants began with modest changes, only daring to make bold and creative reinterpretations in the final few weeks as the project’s operation gained momentum.6 This highlights just how effective the fashion system is at maintaining exclusive authority over the production of clothes and dreams. In a society of de-skilled wearers, these acts of customisation inspire consumers to ‘do’, lowering the threshold between producer and consumer. Italyan Avlusu celebrated action, rather than passive consumption. Modifying existing garments is not a move against, but within existing fashion frameworks to repurpose them and disempower the mass-production of homogenised wearer experiences.7 Fashion hacking demystifies and democratises garment-making techniques so consumers can build their own personal narratives. Indeed, customising clothes dispels fashion’s promise that it offers consumers something they cannot do themselves.

This hacktivism also brings fashion’s crusade to forget into a critical spotlight. As part of the workshop’s customisation process, participants answered a reflective survey asking why they bought their used garment initially, why they don’t wear it anymore and what it means to them on a personal level. This documentation was compiled with a photo of the garment and its original wearer. For some, reflecting on such memories enabled a sudden realisation of the garment’s precious value, overshadowing its previous insignificance.8 Reflection also revealed some garments lead a completely anonymous life in one’s wardrobe – emotionally, they are a blank canvas significant to nothing in particular, synonymous with the forgettable routines of everyday.9 Whether unchanged or transformed, personal reflection reconfigured the meaning of these garments to insert them back into the use cycle, liberated from their outdated image prescribed by the industry.

Italyan Avlusu culminated in a pop-up store where the work-shopped garments could be swapped or traded for an item the customer was wearing that day. Customers also completed the reflective survey for their garments, entering the store equipped with a story to tell.10 Transformed into narratives, these garments trigger awareness of one’s emotional connection to clothes otherwise overshadowed by fashion’s rejection of the immediate past on its ceaseless quest for all things new. Importantly, Italyan Avlusu did not oppose consuming fashion, but instead demonstrated an open dialogue between clothing and wearer, where consumption is an exercise in reflection, self-empowerment and shared experience. Rather than aestheticising sustainable action which keeps consumers disengaged, the project promoted an interactive, meaningful use-phase – a beginning rather than an end for clothing.

To understand the project further, I decided to have a go at this reflective exercise. Taking an old grey sweater – once a favourite that had since been adorned with paint spots, I still liked its shape and fit but I had ceased to wear it. Tracing the memory of these marks, I stitched over the stains in contrast colour, raised up like scars. During the process, I was confronted by the realisation that fashion prescribes newness an almost sacrosanct status, frowning upon the worn or hand-made aesthetic. Rethinking these standards of taste could widen the spectrum of beauty accepted by fashion to destabilise the stigma of visible hand-work in fashion. While sentimental reflection could encourage a bad case of hoarding, this practice can instead inspire more meaningful – and sustainable – post-consumer behaviour. Well-loved garments might be passed onto friends, donated to textile workshops, re-made into other objects, or even become bedding at animal rescue centres. Ultimately, these alternatives bypass the apparent waste generated by the fashion industry.

Italyan Avlusu demonstrated the possibilities for sustainable fashion, free from the stereotypes and commodification normally assigned to eco-friendly style. By reinforcing the relationship between emotional and material durability, consumers can lead sustainable fashion action from the stories worn into their wardrobes.

Nader, R. 2013. “Seeking sustainability”. Huffington Post. May 10 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ralph-nader/corporate-sustainability_b_3254162.html ↩

Styles, R. 2013. “Is green the new black?” Daily Mail U.K. September 14 http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-2420766/Is-green-new-black-Vogue-boss-Anna-Wintour-takes-time-LFW-schedule-premiere-eco-fashion-film.html ↩

Von Busch, O. 2004. Italyan Avlusu. P.01 http://www.kulturservern.se/wronsov/italyanavlusu/italyan_BookletODA-transCS.pdf ↩

Gwilt, A. Rissanen, T. 2011. Case Study: New Materials for Fashion in Shaping Sustainable Fashion. P. 39. Earthscan: London ↩

Cradle-to-grave is the process of use from design to disposal that typically defines the current, unsustainable lifecycle prescribed to most fashion product (Random House Dictionary 2013 ↩

Von Busch, O. 2004. Italyan Avlusu. P.06. http://www.kulturservern.se/wronsov/italyanavlusu/italyan_BookletODA-transCS.pdf ↩

Von Busch, O. 2004. Italyan Avlusu. P.01. http://www.kulturservern.se/wronsov/italyanavlusu/italyan_BookletODA-transCS.pdf ↩

Fletcher. K. 2008. Chapter Seven: Speed in Sustainable Fashion and Textiles: Design Journeys. P.168. Earthscan: London ↩

Von Busch, O. 2004. Italyan Avlusu. P.06. http://www.kulturservern.se/wronsov/italyanavlusu/italyan_BookletODA-transCS.pdf ↩

Von Busch, O. 2004. Italyan Avlusu. P.03. http://www.kulturservern.se/wronsov/italyanavlusu/italyan_BookletODA-transCS.pdf ↩