A hard-wearing cotton twill fabric, typically blue and used for jeans and other clothing. From late 17th century (as serge denim): from French serge de Nîmes, denoting a kind of serge from the town of Nîmes.

Oxford English Dictionary

JEANS ARE ONE OF the most powerful clothing icons of the twentieth-century. Famously named after the French town of Nîmes where the characteristic twill that forms the denim fabric originated, the etymological origin of the word is surprisingly literal: the simplification of the phrasing ‘de Nîmes’ into a single noun.

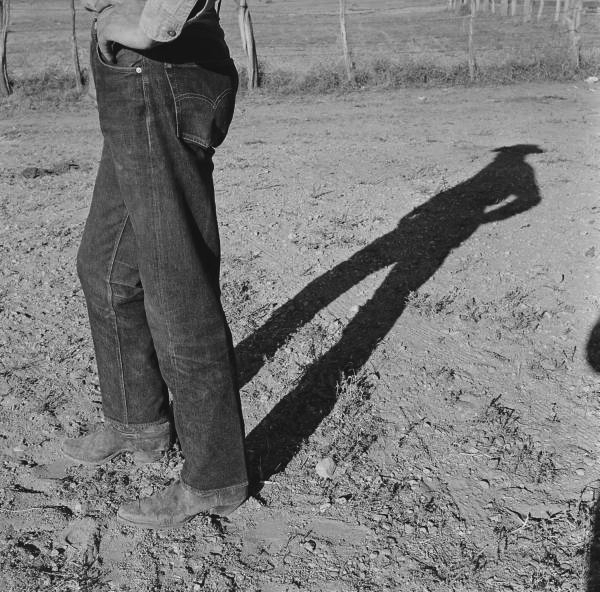

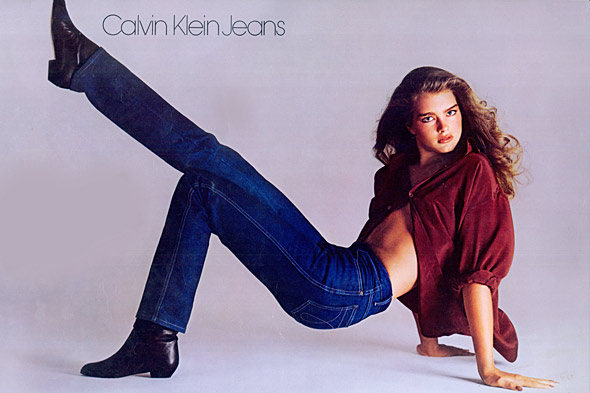

From their European origins, denim was adopted into American culture as a fabric ideal for workwear. During depression-era America, images of sharecroppers and farm workers in denim (like those by Walker Evans in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men from 1941) linked the fabric with the image of the ‘every man’. This symbolism was revived in later years with the rebellion of youth culture during the 1950s: the image of James Dean in a white T-shirt and jeans, for instance, is now embedded in the American iconography. Later, during the 1980s, Bruce Springsteen capitalised on this potential with his ‘Born in the USA’ tour and album. The cover (and the clothes he wore on stage for the tour) depict the singer, blue-jean clad, against the backdrop of the American flag, the blue of the denim fabric echoing that of the stars and stripes.

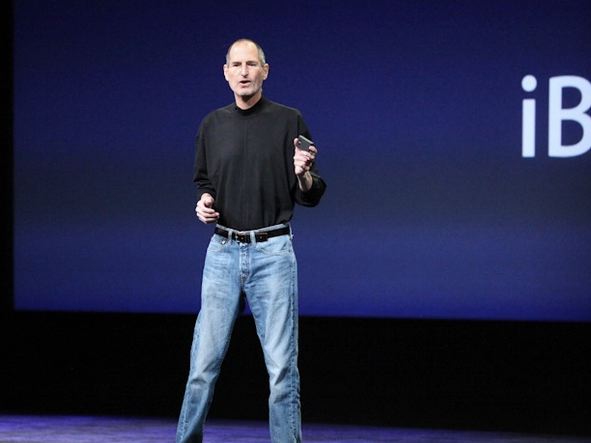

Today jeans have the capacity to connect to almost everyone, traversing the fashion industry from mass production to high-end. But for all the incarnations, a pair of jeans still bears most of the key features that distinguish them from just any pair of trousers: the twill fabric, the top-stitching, waistband, rivets, fly and belt loops. This makes them not only pervasive, but also singular as a powerful clothing archetype.

***

Further Reading:

SUSAN: You know, I really like those new jeans Jerry was wearing. He’s really thin.

GEORGE: Not as thin as you think.

SUSAN: Why? He’s a 31. I saw the tag on the back.

GEORGE: The tag, huh?

SUSAN: Mmm-hmm.

GEORGE: Let me tell you something about that tag. It’s no 31, and uh… let’s just leave it at that.

SUSAN: What are you talking about?

GEORGE: He scratches off a 32 and he puts in 31.

SUSAN: Oh, how could he be so vain?

GEORGE: Well, this is the Jerry Seinfeld that only I know. I can’t believe I just told you that.

Seinfeld, episode 119, ‘The Sponge’, aired December 7, 1995 on NBC

A few weeks ago, Luca Goldoni wrote an amusing report from the Adriatic coast about the mishaps of those who wear blue jeans for reasons of fashion, and no longer know how to sit down or arrange the external reproductive apparatus. I believe the problem broached by Goldoni is rich in philosophical reflections, which I would like to pursue on my own and with the maximum seriousness, because no everyday experience is too base for the thinking man, and it is time to make philosophy proceed, not only on its own two feet, but also with its own loins.

I began wearing blue jeans in the days when very few people did, but always on vacation. I found—and still find—them very comfortable, especially when I travel, because there are no problems of creases, tearing, spots. Today they are worn also for looks, but primarily they are very utilitarian. It’s only in the past few years that I’ve had to renounce this pleasure because I’ve put on weight. True, if you search thoroughly you can find an extra large (Macy’s could fit even Oliver Hardy with blue jeans), but they are large not only around the waist, but also around the legs, and they are not a pretty sight.

Recently, cutting down on drink, I shed the number of pounds necessary for me to try again some almost normal jeans. I under-went the calvary described by Luca Goldoni, as the saleswoman said, “Pull it tight, it’ll stretch a bit”; and I emerged, not having to suck in my belly (I refuse to accept such compromises). And so, after a long time, I was enjoying the sensation of wearing pants that, instead of clutching the waist, held the hips, because it is a characteristic of jeans to grip the lumbar sacral region and stay up thanks not to suspension but to adherence.

As a result, I lived in the knowledge that I had jeans on, whereas normally we live forgetting that we’re wearing undershorts or trousers. I lived for my jeans, and as a result I assumed the exterior behavior of one who wears jeans. In any case, I assumed a demeanor. It’s strange that the traditionally most informal and anti-etiquette garment should be the one that so strongly imposes an etiquette. As a rule I am boisterous, I sprawl in a chair, I slump wherever I please, with no claim to elegance: my blue jeans checked these actions, made me more polite and mature. I discussed it at length, especially with consultants of the opposite sex, from whom I learned what, for that matter, I had already suspected: that for women experiences of this kind are familiar because all their garments are conceived to impose a demeanor—high heels, girdles, brassieres, pantyhose, tight sweaters.

Umberto Eco ‘Lumbar Thought’, 1976, published in Faith in Fakes, Minerva, 1986.

Alright

Well my jeans they are a frayin’

And don’t talk Levi’s because I’ve tried

My hips they had no room to play in

and my little bum felt all trapped inside

There’s Levis all around

If there was Wranglers I would know

I’d turn the whole store upside down

and they don’t got Wranglers so let’s go

I said my jeans they are a frayin’

I said my jeans they are a frayin’ very badUh oh

Why not Levis?

Why not Levis?

Cause they never seem to fit me

No matter what the size

Why not Levis?

Why not Levis?

Well the bum never fits, nor the hips nor the thighs

I said my jeans they are a frayin’

Oh my jeans they are a frayin’ real badThis store’s got Wranglers in ’em

Even got size 31

28 bucks- now wait a minute

But these jeans they’re almost done

My jeans are nearly rags

My jeans are almost dead

And they’ve lost their little Wrangler tag

And you can see my knees right through the threads

I said my jeans oh they’re a frayin’

Oh my jeans they are a frayin’, real badTell them

His jeans they are a frayin’ so bad, so bad.

Yeah you said it.

His jeans are frayin’ so bad, so bad.

What about it?

My jeans, My jeans.Ok fellas.

Doo didoo doo doo di doo doo doo doo doop de doo de doo doo doo

doo doo de doo doo.Jonathan Richman, ‘My Jeans’, 1985.

Try—I cannot write of it here—to imagine and to know, as against other garments, the difference of their feeling against your body; drawn-on, and bibbed on the whole belly and chest, naked from the kidneys up behind, save for broad crossed straps, and slung by these straps from the shoulders; the slanted pockets on each thigh, the deep square pockets on each buttock; the complex and slanted structure, on the chest, of the pockets shaped for pencils, rulers, and watches; the coldness of sweat when they are young, and their stiffness; their sweetness to the skin and pleasure of sweating when they are old; the thing metal buttons of the fly; the lifting aside of the straps and the deep slipping downward in defecation; the belt some men use with them to steady their middles; the swift, simple and inevitably supine gestures of dressing and of undressing, which, as is less true of any other garment, are those of harnessing and of unharnessing the shoulders of a tired and hard-used animal.

They are round as stovepipes in the legs (though some wives, told to, crease them).

In the strapping across the kidneys they again resemble work harness, and in their crossed straps and tin buttons.

And in the functional pocketing of their bib, a hardness modified to the convenience of a used animal of such high intelligence that he has use for tools.

And in their whole stature: full covering of the cloven strength of the legs and thighs and of the loins; then nakedness and harnessing behind, naked along the flanks; and in front, the short, squarely tapered, powerful towers of the belly and chest to above the nipples.

And on this facade, the cloven halls for the legs, the strong-seamed, structured opening for the genitals, the broad horizontal at the waist, the slant thigh pockets, the buttons at the point of each hip and on the breast, the geometric structures of the usages of the simpler trades–the complexed seams of utilitarian pockets which are so brightly picked out against darkness when the seam-threadings, double and triple stitched, are still white, so that a new suit of overalls has among its beauties those of a blueprint: and they are a map of a working man.

James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, 1941.