SPENDING TIME WITH NIGEL Cabourn is a little like being carried along by a minor tornado. He talks a mile a minute, makes friends with just about everybody, and is, by his own admission, ‘like the fucking Pied Piper’. Though we sometimes had to fight for attention with various photographers, textile manufacturers, waiters, taxi drivers, receptionists and countless young and pretty girls, each and everyone a new friend of Nigel’s, the appeal isn’t hard to see. Straight talking and twinkly-eyed, Nigel ‘goes around the world talking to people’, building his niche empire along the way. In business for over forty years now, he has seen the industry change and change again. His faithful interpretations of iconic military and mountaineering garments have made him a bit of a celebrity in Japan, and he now spends much of his time on the road, talking up a storm to loyal followers and new aficionados alike. You might think that all this travelling would take its toll on a man past his retirement age. You’d be wrong. Our own evening ended with Nigel offering to walk us home, only to set a pace so fast and furious that we – forty years his juniors – were struggling to keep up. The last we saw of Nigel he was marching down Rue de Rivoli, camo jacket flapping in the wind, an increasingly smaller dot on the horizon…

Anja: You’ve had a real upswing recently in terms of popularity – why is that do you think?

Nigel: I’ve had plenty of ups and downs but I’ve had my own brand forty-three years now. There aren’t many people around who can say that today. It took me sixty-three years to figure it all out so I ain’t that fucking smart. I’m sixty-five now and I started to get really popular when I was about sixty. I was like, ‘Why am I so popular all of a sudden?’ And I realised that it’s because I’m so approachable. I’ve got plenty of personality, plenty to say for myself and I love what I do. I travel around the world and a lot of people know who I am. A lot of people photograph me. All these things are part of the brand. At least my brand has got a character to it. I look like what I am. A twat. [Laughs]

Anja: Your work today is completely based on vintage clothing. When did you first start working with vintage?

Nigel: Well, my first love was pop music. English pop music between 1967–1971 was fucking brilliant! I was a fashion student then and everybody was into flower power. I only went to fashion college for the birds you know. I met this kid when I was about seventeen and he told me, ‘You’ve got to go to this college, it’s full of fucking birds!’ It’s true! But pretty soon I realised I wanted to design menswear, which was unheard of in Newcastle then. Everybody else did either womenswear or children’s wear. And I wasn’t gay like most other male designers. They’re all gay, let’s face it. And they all design womenswear because they want to dress like women and look like women. So it was hard to get inspiration for me back then. When I went to Paris in 1968, all I saw was the couture houses. And of course, they all had gilt chairs and giant mirrors – it was all crap. I thought, ‘What’s this? What have I gotten myself into?’

Anja: Clearly the gilt chairs and elaborate mirrors didn’t put you off fashion for long…

Nigel: True. In my third year of fashion college I started my own business. I was manufacturing everything locally and selling to a radius of about forty miles, that’s what we all did back then. And in 1972 I met Paul Smith who became my agent – he got me into all the London shops. In fact Paul showed me the first vintage garment I ever saw – I didn’t know vintage existed until 1978.

David: What was the garment?

Nigel: It was a RAF jacket, a little short green one with the button and tape. Paul gave it to me and it made me a fortune. Once I discovered that button and tape, I did a whole range of similar pieces in 1979 – I was the first one to do that.

Anja: What were your clothes like before you discovered vintage?

Nigel: When I first started all I did was clothes inspired by pop music, but in the mid-Seventies I lost my way a bit. When I discovered the vintage I got myself fucking up to speed again and I never looked back.

Anja: What do you mean you ‘lost your way’?

Nigel: Well, I was showing in Paris from about 1973–1985. I can’t even remember what I was doing back then. Life’s always been a big rush for me; it’s never been easy. I’ve always been rushing. Everyone thinks I’m on drugs! [Laughs] Truth is, my only drug is the exercise.

Anja: Exercise? Really? What’s your routine?

Nigel: I read a book a couple of years ago and it said that if you want to stay young you’ve got to exercise six days a week. So I thought, ‘I’m up for that!’ Now I get up at 5.30am every morning to go training. I take a ten-pound medicine ball with me when I travel, and I go running with it. When I’m at home I have three trainers: a boxing trainer, a table tennis trainer and a tennis trainer. I train two hours every day, six days a week.

David: That’s very impressive! But back to the fashion… How do you decide on what historical eras to focus on?

Nigel: Mainly that’s to do with the events that took place at the time. For me the 1910s is Robert Falcon Scott and the British Antarctic Expedition, the 1920s are about George Mallory’s Mount Everest expeditions, the 1950s is Sir Edmund Hillary ascending Everest. I always start with a character. I even did a collection based on my dad once – he was in Burma during World War II you know.

David: Do you ever think of who actually designed those vintage garments?

Nigel: That’s a good point. Mountaineering garments would, for example, usually have been designed by someone on the expedition. Clothes were often passed down too. But if an expedition was going up Mount Everest they would probably have employed scientists to work on their gear. The Everest parka I make was originally designed by Fairydown in New Zealand, a company that made sleeping bags.

Anja: A lot of your garments are still made in England, why is that important?

Nigel: Because I’m an old fart. [Laughs] England is my heritage but I also do it because I have control, it looks beautiful and I’m proud of it. I don’t want to make stuff in fucking China.

David: You make quite a few things in Japan too, right? How do you get on with production there?

Nigel: I have partners in Japan, six shops and a full team. I go to Japan five times a year. I have a wife and children and everything there. I’m just joking! [Laughs]

Anja: How did you get big in Japan?

Nigel: It started in 1980. I was showing in Paris and this Japanese man came to my stand. He loved my product and said he wanted to represent me. I was one of the first European designers in Japan. Margaret Howell was there before me, in about 1979, but she’s a bit older than me – thank-fucking-god. Anyway, I arrived the year after. We had the same partner then, Sam Sugure – he’s seventy-one now. The Japanese love British style and they love vintage. If everywhere were like Japan I’d be a multi-millionaire by now.

David: Your brand seems to fit very well with the trend in menswear that’s been around for the past few years: heritage brands, made in Europe, Japan or America with great attention to craftsmanship and details.

Nigel: It’s true that my product is niche. There aren’t that many niche products out there: Engineered Garments is sort of niche, Yuketen is niche, so is Viberg. Visvim is sort of niche, but then he makes it all in China and charges the earth for it. I’m sorry but I don’t see how you can charge £1,000 for a pair of shoes made in China.

David: When you use the word ‘niche’ – what does it mean to you?

Nigel: ‘Niche’ means that something is exclusive, small and beautiful. I’m all about niche. I still support Scunthorpe United, where I was born. I don’t support fucking Newcastle even though I live there! I’ve always been an underdog. I’ve had to fight for everything I get. I compare myself to my football team, which is in the lower divisions of the English football league. You can get from the lower division to the premier league, but you’ve got to be the best.

Anja: You’re a well-known vintage collector by now, but I imagine a lot of the garments that have been the most important to you – Edmund Hillary’s or George Mallory’s mountaineering gear for instance – can’t be bought. How do you get to the garments that aren’t on the market?

Nigel: I’m a nightmare in museums. They all know who I am, and if they don’t know I tell them! And when I go I want everything out too! The only place that hasn’t helped me is the Imperial-fucking-War Museum – I’ve been knocking on their door for twelve months now. The Royal Geographical Society opened their arms to me though. They asked me, ‘Would you like to see George Mallory’s clothes? We’ve actually got them here!’ I was like, ‘You’re fucking joking!’ I picked up his neckerchief – it’s still caked in blood you know. I tell everybody that he went up the Everest in a tweed jacket, but he didn’t really. What happened was that he kept a tweed jacket in his rucksack and whenever someone took a photo, he put it on as the gentleman he was.

Anja: Are there any living men who have inspired you?

Nigel: I’ve worked a lot with Nino Cerruti, he’s a marvelous man. A fucking card. He’s inspired me, I tell you. I bought cashmere from him and made him a duffel coat. He makes amazing fabrics. He employs four thousand people now and he’s eighty-four. You know what he told me five years ago? He said, ‘I was an international playboy until I was sixty. Then at sixty I really started to work’. [Laughs] Well I’ve always been a hard worker but I’ve worked harder between sixty and sixty-five than I’ve ever done in my life! My business had a real facelift in 2003. Not me though. I’m still the same – I have a dropped eyelid and a few other bits and bobs that need sorting out. [Laughs]

Anja: What happened in 2003?

Nigel: I was pretty much on the bones of my arse in 2000. I was doing terrible. Sam Sugure told me, ‘Look, you’ve got to get back to doing things you really believe in’. At the time I was doing a consultancy job for Berghaus and I was digging into mountaineering books for them and I realised that the fiftieth anniversary of Sir Edmund Hillary’s ascent to Everest was coming up. I went to the Lake District to look at his clothes and I couldn’t believe what I found. I just hit lucky, and it changed my whole life. I found images of Hillary and Tenzing and their whole team and their clothes are fucking amazing. I just looked at them and thought, ‘I’m going to fucking make all those clothes’. And I did. And I’m still living on it today. It’s a bit like that song ‘Tell Laura I Love Her’. Ricky Valance recorded it in 1960, and he was still fucking singing it in 1990. Let’s face it, Bill Haley & His Comets, they only had ‘Rock Around The Clock’, but it kept them going a long time!

Anja: How do you decide which vintage garments to work from? Do you alter or update the pieces at all?

Nigel: I do. I Cabournise them. I mean, there’s only so much you can learn from images; at some point I have to decide what fabrics, colours and textures to use. And I can’t have the clothes fitting the way they did in 1950. But I do try to copy the little things when I can, trimmings and things like that. I love all the wooden components from the 1940s and 50s – nobody else makes those.

David: What was the first garment you made in that way?

Nigel: It was the Everest parka, and after that I made the Cameraman jacket. I actually found out that Sir Hillary’s Everest parka still exists, in a museum in Christchurch, New Zealand. I couldn’t get off the plane quick enough to get to the fucking museum! When I saw the Everest parka – well it’s actually the Antarctica parka. I tell everybody it’s the Everest parka, but actually he went across the Antarctica in it. I’ve just rolled it all into one. Everyone thinks he went up the Everest in a red parka, but it was a blue one actually. [Laughs]

David: What’s the value of the – real or imagined – narratives that you spin around your garments?

Nigel: I’m a great romantic – I could tell you stories about every little detail on a garment. People come up to me and ask me why my clothes are so expensive, so I tell them. The stories justify the price you know. What I’m saying is that it’s not just any old garment. The thing is, most people make clothing just for money. I do it because I love making a good product. If I make money out of it, that’s a bonus. If I don’t, it still doesn’t bother me too much.

David: Designer collaborations have become hugely popular the last few years – they’re like the contemporary versions of the licensing deals of yesteryear. You’ve done several – what’s the appeal?

Nigel: Well you make money from it. You loan your name to somebody and they pay you for it. But I don’t say yes to everything. I said no to Moncler. They were doing a collaboration with Visvim but didn’t want to continue and I said to them, I said, ‘If you can’t make a success from working with Visvim, you’re not going to make one with me – we’re two peas in a pod’. And also I asked them about their vintage and they didn’t have any. When I asked them about their customer they were after the same as me so I just thought, what’s the point? I’d be doing a me two. But I could have made a lot of money from it; for those sorts of collaborations you can make £3–400 000.

Anja: Recently you started doing womenswear, after forty years of only doing menswear. How come?

Nigel: Well I met this girl, a real pretty girl she was too. When I first saw her I thought, ‘She looks like a nice girl, I bet she’d be good to hang with’. But she turned out to be a nightmare. She was Hungarian and I’m romantic about the Hungarians because of Ferenc Puskás. Do you know him? I love Puskás. He was one of the best footballers in the world. This girl, she looked like Gerda Taro. At the time I was obsessed with Robert Capa and Gerda Taro and I was thinking about doing something on the Spanish Revolution. But I had to find a British angle, because that’s always my take. I found out that 2,000 British civilians volunteered to go there and so I did the story on them. And Robert Capa of course. I roll it all in. And what I don’t know, I make up! Anyway, so I worked with this girl for eighteen months on the womenswear. We travelled all over the place. I didn’t lay my hands on her or anything – I’m not like that! I just liked her company. And she looked like Gerda Taro. Have you seen Gerda Taro? She got crushed by a tank in 1937.

Anja: Is this girl still working with you?

Nigel: No she ran off. She was completely mad, but I liked her. One day she just flipped and ran off. I was quite shocked actually. Now I have a girl from Dover Street Market who designs the collection. She’s so good. She’s normal and she just fucking gets on with it.

Anja: What does ‘authenticity’ mean to you? Why have you chosen to use it as a tagline?

Nigel: Authenticity means that something is original, and that it comes from a vintage piece. The fabric is real. It’s functional. It does what it says. If I’ve taken a design from a 1950s garment with wooden trimmings, then my garment will have wooden trimmings too. I want my garments to be the real deal. I don’t want anything nancy pansy.

Anja: How does the ‘authenticity’ of a garment change when you adapt a piece intended for practical use – like the military or mountaineering garments you so often use – into a ‘fashion’ garment?

Nigel: You’re asking me deep questions now. I don’t know if my thinking goes that deep most of the time. If my garments happen to be fashion garments, then so be it. They’re only fashion garments because that’s what people perceive them to be – I don’t see them that way. You could still go mountaineering in them. They wouldn’t be so practical because garments today are much lighter than they used to be, but you could still do it. I just do what I do because I love it. I don’t know if I have a better explanation. It’s like when Sir Edmund Hillary was asked why he decided to climb Everest; he said, ‘I just like going up’.

David: Considering that you’ve been working in fashion for over forty years, what changes in the industry have you found the most striking?

Nigel: Fucking hell – they’re endless! When I started in the 1970s everybody wanted to help me. I got a £6,000 loan from the bank, just based on the fact that I looked like a nice young lad. You didn’t have to put your house up back then – bank managers were willing to take a chance. And then there’s all the new technology. Until 1982, before the fax machine, we had to send everything by courier. And the last ten years the mobile phone has changed everything again. My daughter has taught me how to send emails with my phone. I still can’t send emails with the normal computer. [Laughs] Fucking technology is frightening – you know, for an older person. I get loads of help. My boxing coach tells me ‘Nige, you’ve got someone doing everything for you!’

Anja: Except the training.

Nigel: Yeah, except the training – I’ve got to do that myself! [Laughs]!

This article was originally published in Vestoj On Fashion and Slowness.

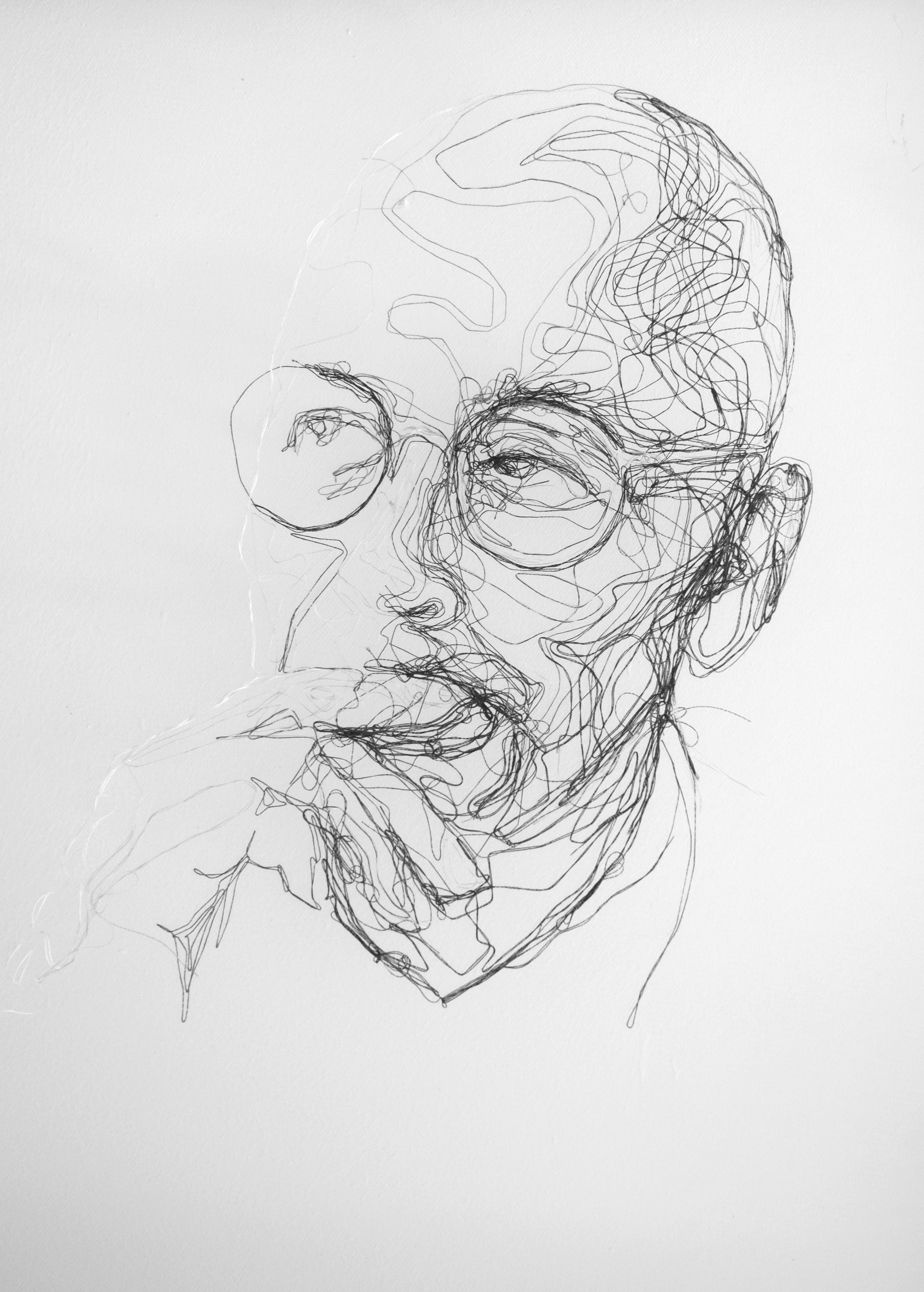

Louise Riley is a London-based textile artist and illustrator.

David Myron is a Paris-based cabinet-maker and set designer as well as the original Big Monkey.

Anja Aronowsky Cronberg is Vestoj‘s Editor-in-Chief and Publisher.