FEW DIRECTORS HAVE BEEN as prolific in their lifetime as Kenneth Anger. Blending surrealism and the occult with homoeroticism, psychodrama and unashamed spectacle you could perhaps say that Anger’s whole vocation has been an ode to the art of magic. An early follower of Aleister Crowley’s teachings, Anger at various stages in his life mixed with occult practitioners and artists as diverse as Jean Cocteau, Anaïs Nin, Anton LaVey, Mick Jagger and Jack Parsons, and his life is as shrouded in myth and legend as his work is. Kenneth Anger is today as dapper as he ever was, and each and every one of his works is testament to the fact that this is a man for whom the sartorial matters. In the studded leather jackets, patchworked silk robes or bejewelled head-dresses of his characters you can find his devotion to the vogue of the times, and despite restrained budgets the viewer never fails to feel enriched.

Aaron Rose: This interview is going to be a bit different from the usual ones because we are going to speak about fashion and in particular costume…

Kenneth Anger: Yes. It’s great! You know I’ve just come from Paris where I was invited to the opening of the Valentino show.

Aaron: Yes, I would love to talk about that, but if it’s ok let’s go back for a second. My assignment here is to write about fashion and the occult, but since you are not a fashion designer this would really be more about costumes. When did you first start thinking about costumes?

Kenneth: Well, the story behind that is that my grandmother, her name was Bertha Coler, she was also known as Big Bertha, she was a costume mistress and a designer, who looked after the costumes during the silent film period in Hollywood. The most notable film that she worked on was The Eagle in 1925. It was one of the films starring Rudolf Valentino. It was the only swashbuckling action film that he made. It was done a little bit in the spirit of Douglas Fairbanks films.

Aaron: So you grew up around costumes?

Kenneth: Yes, and then when my grandmother died she left me her collection of robes from the films that she had worked on. This included some costumes from Clara Bow films, and of course these costumes are very fragile! Silk is an organic substance and it has to be looked after very carefully or the fibres will tear. I gave all those costumes to the British Film Institute in London some years ago. I don’t think they have put any of them on display, but they do have them.

Aaron: When I was first given this assignment I immediately thought of the opening scene from your film Puce Moment where you have all the vintage dresses sliding towards and tearing away from the camera.

Kenneth: Yes! Those belonged to my grandmother as well. They are different dresses from the 1920s – from the Jazz age. Those are flapper dresses.

Aaron: Why did you decide to tear them away like you did?

Kenneth: Because in the slightly satirical idea behind that particular short film, the girl in the film is supposed to be sorting through her closet to find the dress she wants to wear. So she’s pulling one after another off the rack, then looking at it and tossing it aside.

Aaron: It seems as though costume and fashion have played a major role in most of the films you have made. Why is that?

Kenneth: You have to consider the fact that I’ve never had budgets; my films have always been very modestly produced by myself. I mean, my entire budgets are what a major film would spend on hairpins! But costumes are important. I’ve used a lot of uniforms and I do consider those costumes…because they are. They’re not ordinary street wear. I’ve made several films with military uniforms, and finally I made a film recently called Uniform Attraction, which is about the fetishistic interest in military uniforms. In fact, I don’t care whether it’s a policeman or an orderly in a hospital or a fighter in an army; the purpose of uniforms ever since Roman times is to transform a person from a civilian into a unit. So the fact that everyone wears the same type of uniform makes you into a cohesive unit.

Aaron: Weren’t the costumes in your first film uniform related?

Kenneth: Yes. Fireworks has the white summer uniforms, they’re called Summer Whites of the United States Navy. Those were genuine uniforms too! In other words, I used real sailors in my films. I didn’t have to hire the uniforms from a costume house, so they are authentic because the uniforms are real and so are the bodies inside.

Aaron: Symbolism is very important to you. You seem to continually reference the fact that things in life happen by chance and I’m wondering if that plays into the symbolism you use in the costumes for your films?

Kenneth: It definitely does. I know what I’m doing. I’m not what you’d call some kind of drug-crazed maniac like some other film directors. I’m talking about somebody like Jack Smith who was kind of crazy. I knew him quite well and I even helped him on a couple of his projects, but I’ve had a longer life span than Jack.

Aaron: Well, it seems like everything you do has a very specific meaning, as well as very strong historical and personal ties.

Kenneth: I hope so. You know, I’m making personal films. I’ve never tried to break into the commercial film world because I like making short films. I don’t like making three-hour films or even two-hour films. I also like working with found footage. The film I made on the Hitler Youth is using found footage that I got from the Imperial War Museum in London. They were the boy scouts of Hitler’s Germany.

Aaron: Which is again very costume oriented…

Kenneth: Oh absolutely! Of course if you take off the armbands with the swastikas, what the boys are wearing with the short pants and beige colour are practically identical to the traditional Boy Scouts! The Nazis copied the Boy Scouts. The Nazis took it over for their future brainwashed warriors. I don’t know how much you now about the Boy Scouts, but the idea at the beginning was always to prepare the boys to go into military service.

Aaron: I didn’t know that…but it makes a lot of sense. I’m starting to grasp the historical references, but what is your personal connection to uniforms?

Kenneth: Well, I served in the United States Navy when I was a teenager in the closing days of World War II. I didn’t do the whole term because I came down with scarlet fever. I do have a photo someplace of me in a sailor uniform.

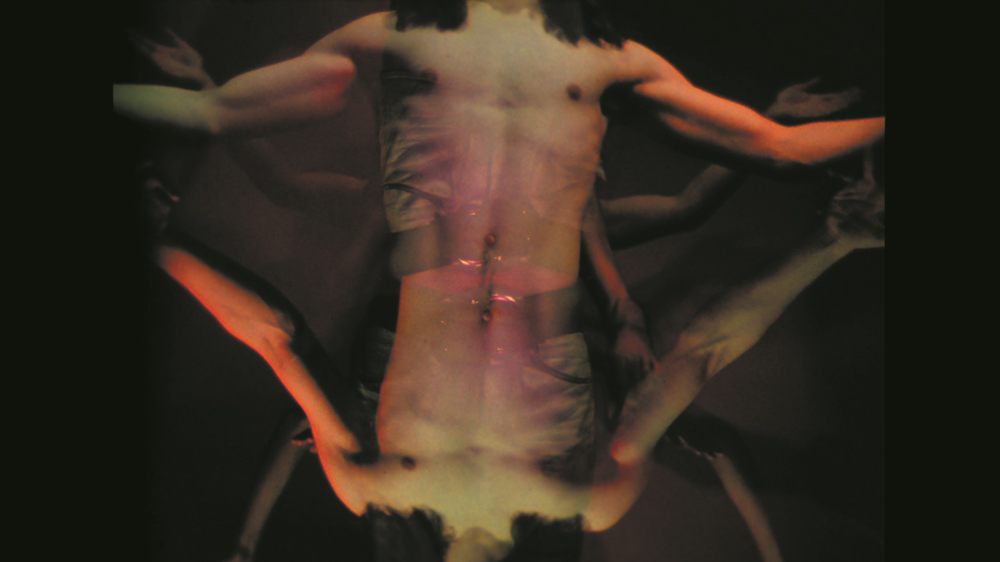

Aaron: Let’s switch gears for a minute. In preparation for this, I was looking back at your film, Invocation of My Demon Brother and I noticed that the way you shot that film is very reminiscent of the trends in fashion photography from that time. Were you looking at those fashion images for inspiration?

Kenneth: I have always been very aware of fashion, and I certainly looked at a lot of it. I mean, not just Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue… and after I moved to Europe, in Paris in the 1950s, I became a friend of Yves Saint Laurent. This is just when Yves took over from Christian Dior and I was invited to some of those early shows.

Aaron: So you were aware of what was happening in fashion imagery at that time?

Kenneth: Oh yes! Absolutely. However I’ve never gone into commercial work. Luckily that’s something that I’ve never felt like I’ve had to do because I had enough money to get by in my bohemian lifestyle. However, if I ever had to go commercial, I probably would have chosen something in fashion.

Aaron: I’ve noticed in your films from the 1960s and 1970s, there seems to be repetitive symbolism in your costumes. In particular, images of triangles or motifs of eyes and such. Is there a reason for this?

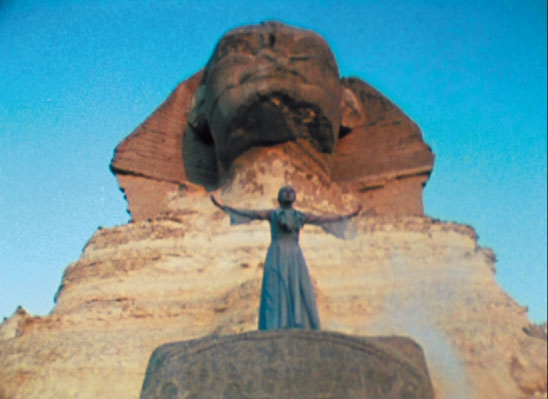

Kenneth: Well, yes. Like in Lucifer Rising, the triangle is a symbol of the pyramids in Egypt. The triangle shape is an occult symbol for fire. That’s an upward pointed triangle. A downward pointed triangle is a symbol for water. These are ancient symbols and they are very simple. When you combine the two you make a Star of David. Many people don’t know that.

Aaron: What was the personal significance to you in using the triangular patterns?

Kenneth: I am a member of the OTO, which is like an honorary organization that means Ordo Templi Orientis. I’ve been a member for years. It was founded by Aleister Crowley back around 1910. It’s a little bit like the Freemasons or something like that. But I don’t go to meetings. In other words, I’m an honorary member, but I don’t have to really do anything. I know a few of the other people involved and I’ll speak to them when I run into them, but I’m not a club type of person. I’m a loner. I am definitely on the occult wavelength, but I prefer to work alone.

Aaron: But you’ve most certainly pulled references from the occult into your films…

Kenneth: I hope so! I do that for my own pleasure and whether they are understood by the general audience I don’t care! They are there, and I think they have a power and an invocation. Whether you see or you understand the power of an eye in a triangle, that still has a whole occult background. Like the Seeing Eye, that symbol goes back hundreds, maybe thousands of years! So maybe I’ll just flash it at you for a few frames, you know, very quickly.

Aaron: I’m curious why, if you describe yourself as a loner, you belong to this club and reference uniforms and organizations so much in your work?

Kenneth: Well, with regard to the OTO, as I said, I don’t go to their meetings, but I’ve never been expelled. In other words, I haven’t given away any of their secrets. They sometimes will say to someone, “Well you know you haven’t paid your dues, or you’ve told someone something you weren’t supposed to.” But I haven’t done that. On the other hand, I’ve studied Aleister Crowley my whole life, and it’s no secret that he involved actual lovemaking as part of his magic. So that could be interpreted as being some kind of sex scandal, if you want to look at it that way. You know, his idea that making love can be part of magic or ceremony? That doesn’t mean it happened all the time, though. It was occasional…like when the moon was right or something.

Aaron: Were those ideas something that you have tried to communicate aesthetically?

Kenneth: Well, yes, in my own personal way. But I’ve never filmed a ritual. I’ve always filmed a kind of a vision…like as if you were looking into a crystal ball. Not using dialogue or speech. I always use music. That’s my own personal style of interpreting these things.

Aaron: That’s one reason why I love your style. You’ve never had to show actual sex to make it sexy.

Kenneth: That’s right. I think it’s better. Suggest rather than show. Pornography is boring! I mean, so what? It’s in, then it’s out, then it’s in again. When you’re actually performing in a sexual way with someone that you’re attracted to, you forget that it’s sort of just “in and out and in and out.” That doesn’t matter! It becomes like a symphony…and it should be! Hopefully! There’s supposed to be an art to lovemaking.

Aaron: Are there ways that you can specifically speak of where you’ve referenced that symbolically in your costumes?

Kenneth: Well, I think costumes and clothing in general are more interesting than the naked skin. That’s just my own interpretation. The motifs that I have recurring over and over again in my films are not about striptease. It’s the opposite. It’s about dress up. I always show people dressing. They are putting clothes on rather than taking them off. So it’s the opposite of striptease. It’s playing dress-up. To me that is how people really express themselves. Through clothes or costumes. I particularly like the motorcycle fellows in Scorpio Rising. Those are not actors. They are genuine working class fellows that love their motorcycles.

Aaron: Yes…and nobody is getting undressed in that film. They are all putting on their gear…

Kenneth: That’s right. That’s the Kenneth Anger touch.

Aaron: Is that symbolism related to a way you live life spiritually? I’d like to go back to this idea of chance, or rather the lack of chance in life. The idea of pre-determination. It seems like everything in your life and work fits together like pieces of a puzzle…

Kenneth: Well, it’s nice to believe that you have a favourable guardian angel or something, but it’s all a fairytale. In other words, I don’t really believe that. But I have had fortunate happenstances in my life where things seem to fall into place. Either I have a situation where the people I work with are ideal, like the poetess Anaïs Nin, who I knew when I made Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, and she agreed to appear in it. Also, Marjorie Cameron, who in real life has bright red hair, became my scarlet woman in the film. So those things just kind of fell into place.

Aaron: Are there any other aesthetic choices that you’ve made that were driven by coincidence?

Kenneth: Well, I just go with the flow. For instance, when I was living in England in the 1960s, it just so happened that I was friends with Marianne Faithfull. She was recovering from drug addiction at the time, and I cast her as a devil in my film Lucifer Rising. She played Lilith. Lilith is a powerful female demon from the Babylonian times. But working in my film, when she was recovering from her heroin addiction, was kind of a therapy for her. I told her at the time that she was playing Lilith, but the real idea of the character was to get the demon out of her system.

Aaron: Looking back on all these films you’ve made, and specifically in relation to the costumes, is there anything that you wish you had done differently?

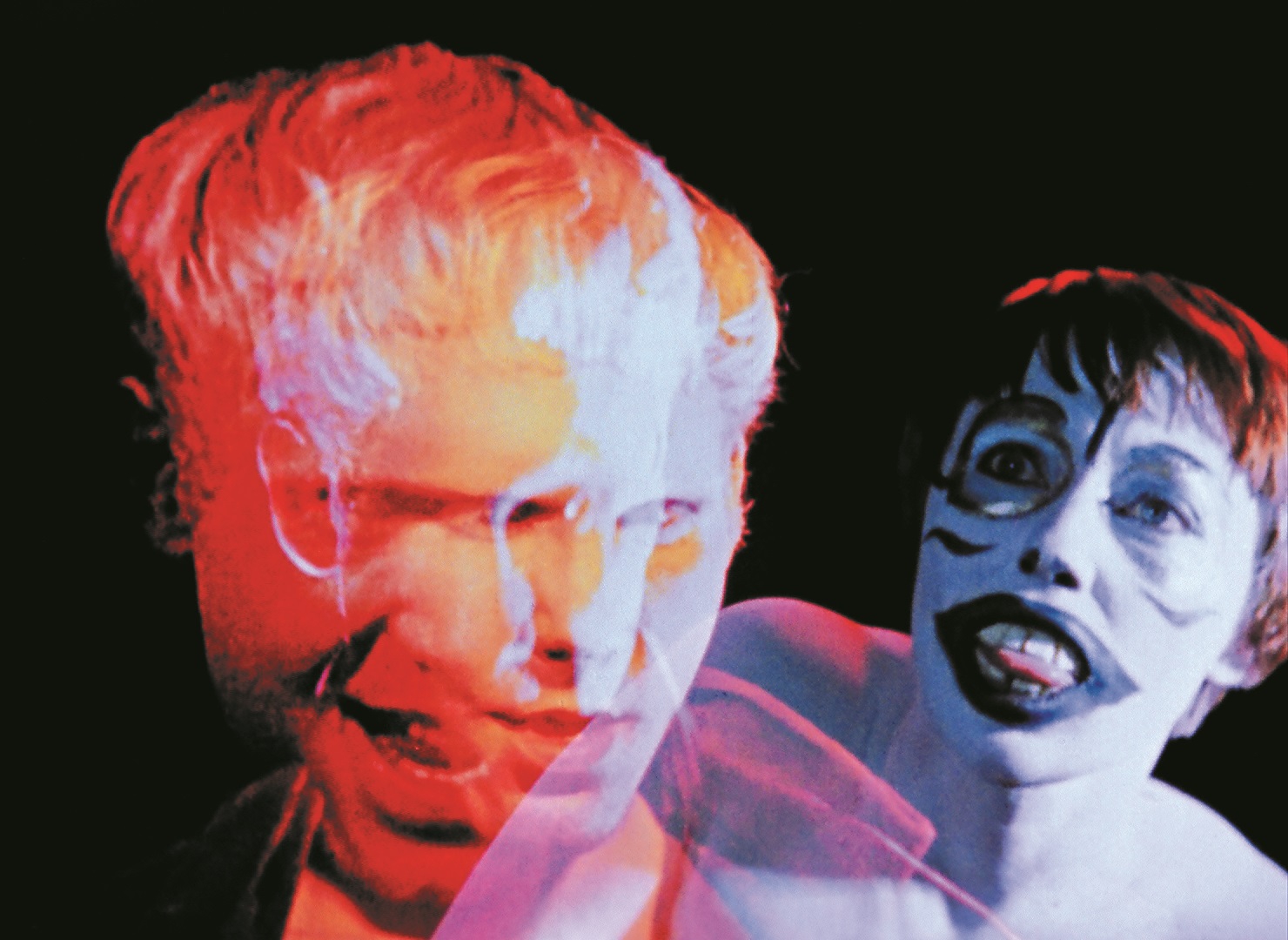

Kenneth: Well, it isn’t that I wished anything was different, it’s just that there were ideas that I had that were beyond my means. So with the films that I’ve realised, I’ve just managed to do them and get through them, but there are other ideas that I’ve had that I wished could have been different. For instance, my film Rabbit’s Moon. I made all those costumes myself. That was Pierrot, you know the sad clown, he is basically just in a large white T-shirt. It’s silk, and it’s very loose…like white pyjamas. But he’s always shown in a kind of sloppy white suit with buttons on the front and then a white skull-cap and white paint on his face. He’s dedicated to the moon. That’s why he’s in all white. His rival is Harlequin, and Harlequin has quadrangles on his costume…

Aaron: And you made all of those costumes?

Kenneth: I made them, but I also had some help. I had somebody to work on the sewing machine for me. Then as for Columbine, she’s the girl who teases and torments Pierrot, and then he falls hopelessly in love with her. Yet she is the actual demoness of Harlequin. Harlequin is actually Lucifer. In other words, he is the devil. In the film he is shown as a playful devil, in other words, playing pranks. I show, in Rabbit’s Moon, that Columbine is just a projection out of the magic lantern of Harlequin.

Aaron: What about in your later films? Did you continue to have a big say in the costumes or were there other people making those decisions for you?

Kenneth: Well, when I was living in England I had Jann Haworth. At the time she was married to the artist Peter Blake. I met her at the Robert Fraser Gallery in London, and I asked her if she would like to work on some costumes for me. However, for the most part, I designed them. For instance, the coloured satin Lucifer jacket with the rainbow spectrum on the back, and then the letters in gold leather that spell out Lucifer, those were personally made for me by Jann. It was a good collaboration. That jacket that she made, I donated to the British Film Institute. They never displayed it, but they have it.

Aaron: What about the motorcycle jacket from Scorpio Rising? Who has that now?

Kenneth: Well, I actually made that one. In other words, I did the lettering on it. I used those chrome studs. So I did all that, which is basically pretty easy. You just draw it on the leather and then stick these chrome disks on it. I actually gave that jacket away. One of the motorcycle guys that worked on my film and used to ride me around on the back of his Harley asked for it, and I said, “Ok, take it,” and he just rode off in it on his motorcycle. That was the last I saw of it.

Aaron: You know fashion is something that is so flighty. It’s a transient medium. Yet films for the most part aren’t created that way…

Kenneth: The diabolical thing about fashion is that they are supposed to come up with new ideas for every season, but the seasons, especially as you get older, seem to come faster and faster. Suddenly you have to come up with new ideas, all of a sudden it’s a new season, and what they have discovered is that they can pick up ideas that have gone before and simply retread them. So I think it’s amusing to see some of these ideas come back. You know, in the 1940s when I was growing up it was wartime. It was also the time of Joan Crawford, who was very beautiful then. They began to dress in a mannish fashion, with padded shoulders. Because there was a war going on, they had a more military look, even though they were not in the military…and they’ve brought that back a couple of times. Then there were clogged shoes…

Aaron: This seems like a good segue to speak about the Valentino show that you did recently in Paris…

Kenneth: There are two young designers, who I believe are both Italians, who did this latest Valentino show. Valentino himself is the producer, but he’s not directly involved in the design anymore. Anyway, they approached me to do the light show behind this year’s runway presentation in Paris. It was done outside of the city in what’s normally an industrial space. It’s a big warehouse. It’s longer than a football field. Everything was white. There were white benches for the people to sit on, and white walls, white seats and white cushions. So three walls are white and on these they projected images from my films that I personally chose. They were mostly images from Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome. They are quite Baroque images with a lot of oranges and hot colours.

Aaron: Were you cited as an influence for the collection itself?

Kenneth: The colours from my images were only occasionally echoed in the clothes on the runway. It wasn’t like they copied images off of the screen or anything. But anyway, so these images from Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome were projected on the walls during that half hour before the show while people are being seated. Then, when the runway was happening, they used only images from my Tivoli Fountain film, which were in blue. So there were all these water images that made a wonderful background for the runway show.

Aaron: Did you love it?

Kenneth: Yeah! As a matter of fact, I may try to do something like this again in America. They used nine projectors pointed from the ceiling. Everywhere were these abstract water effects of these splashing fountains. It worked really well. Because of all the water, there was this kind of exuberance going on.

Aaron: How did it feel to sit there and watch that?

Kenneth: It was delightful because I’ve never seen my films shown on nine projectors at once! It was great. I was very happy with it. The Valentino people were very nice to me.

Aaron: At times you’ve mentioned that you saw the cinema as an evil force. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

Kenneth: Well, I happen to be a prankster in a sense. A trickster or a prankster. Lucifer tends to be a sort of prankster figure in my imagination. So when I say it’s evil, I mean evil on my terms. I don’t mean evil like, let’s say, the Nazis or something. My conception of evil is something that becomes an obsession. Cinema has become my obsession. In a way I’d like to move away from it and just be free for the last period of my life. I’d love for this period to be one of meditation or contemplation, but it’s not going to happen because I still have ideas for films I want to do. It never lets me go.

This article was originally published in Vestoj On Magic.

Aaron Rose is a director, artist and curator based in Los Angeles.